You’ve Been a Good Old Wagon, Crawdad Song, and other derivatives of Frog Went a-Courtin’

___________________________________________

originally published on 29 November 2013; latest edit: 11 November 2020

___________________________________________

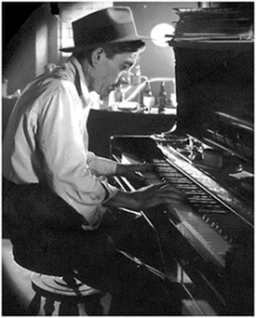

Benjamin Robertson “Ben” Harney (6 March 1872 – 2 March 1938) was a songwriter, entertainer, and pioneer of ragtime music. His 1895 composition “You’ve Been a Good Old Wagon but You Done Broke Down” is regarded as one of the first published ragtime songs. In 1924, the New York Times wrote that Ben Harney “probably did more to popularize ragtime than any other person.” Time Magazine termed him “Ragtime’s Father” in 1938. — from the Wikipedia profile of Ben Harney

Benjamin Robertson “Ben” Harney (6 March 1872 – 2 March 1938) was a songwriter, entertainer, and pioneer of ragtime music. His 1895 composition “You’ve Been a Good Old Wagon but You Done Broke Down” is regarded as one of the first published ragtime songs. In 1924, the New York Times wrote that Ben Harney “probably did more to popularize ragtime than any other person.” Time Magazine termed him “Ragtime’s Father” in 1938. — from the Wikipedia profile of Ben Harney

You’ve Been a Good Old Wagon But You Done Broke Down (Harney & Biller) — Ben Harney and John Biller

Ben Harney sings a cappella, in a performance recorded by the archivist Robert Winslow Gordon, possibly in 1925* (Gordon Cylinder G24)

.

(above) The style of Harney’s song in the Gordon recording does not seem to exemplify ragtime. In this recording, reportedly the only existent one of “The Father of Ragtime” performing, Harney sings a folk song, in a simple “country” style. Which folk song? Read on…

(below) Jamie Levac plays solo on an 1869 square grand piano made in London, Ontario. Well done. But I would like to ask Mr. Levac why that’s not “Frog Went A-Courtin’.” The same question must be asked of Harney’s recording.

.

From an article on a page of the Library of Congress website (loc.gov), under the title Folk-Songs of America: The Robert Winslow Gordon Collection, 1922-1932:

The tune [Good Old Wagon] is similar to that of “The Crawdad Song,” and almost all the verses can be found in standard folksong collections. For instance, a single collection—Volume III of the Frank C. Brown omnibus from North Carolina—contains at least four songs which have elements of either verse or structure which parallel “The Wagon”: “The Dummy Line” (p. 521), “Sugar Babe” (p. 550), and “Went Down Town” and “Standin’ On The Street Doin’ No Harm” (p. 562). Of course, because Harney published his text in 1895 and performed it frequently for the next thirty years, it is quite possible that at least some of the texts recorded by folksong collectors during the early decades of this century reflect the popularity of Harney’s song.

In an article in the journal American Music, in Volume 13, No. 2 (Summer 1995), titled “Ben Harney: The Middlesborough Years, 1890-93,” by William H. Tallmadge (p. 167ff.), on page 181 Tallmadge provides a quote from the book Best Loved American Folk Songs, 4th ed., by John A. Lomax and Alan Lomax (New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1953 [1947]), p.83, in which the authors apply the term “Negro blues” to the traditional song “Sweet Thing.” In the same paragraph (pp. 180-181), Tallmadge, perhaps following the lead of the Lomaxes, uses the similar phrase “African American folk blues” when referring to the traditional song family that includes “Sugar Babe,” “Sweet Thing,” and “Crawdad Song,” which he says Harney “created a ragtime version of” in writing “You’ve Been a Good Old Wagon but You Done Broke Down.”

Not Blues

As pointed out by Joseph Scott in 28 January 2017 and 4 September 2019 comments on this page, the application of the term “blues” to the “Crawdad Song” family of songs is irregular and a mistake that the earliest blues researchers would not have made, since the “blues” genre emerged at a considerably later date than did the traditional song family to which “Sweet Thing” belongs. Therefore, the identification by the Lomaxes c. 1947-1953 of “Sweet Thing” as a type of “blues” is a misuse of the word. Tallmadge evidently also misapplied the term “blues” in his 1995 article on Ben Harney in referring to “African American folk blues.”

After agreeing with the Lomaxes on the influence of the originally African American traditional “Sweet Thing,” and by extension other members of the same song family,  on white banjo and guitar pickers who adopted and parodied it in creating their own songs, in considering this family of songs Tallmadge notably concludes (p. 181) that “the basic folk tune common to the many variants, both black and white, derived from the much earlier British folk song A Frog He Went a-Courting.”

on white banjo and guitar pickers who adopted and parodied it in creating their own songs, in considering this family of songs Tallmadge notably concludes (p. 181) that “the basic folk tune common to the many variants, both black and white, derived from the much earlier British folk song A Frog He Went a-Courting.”

“Frog Went a-Courtin'” links:

_______________

The opinion of the distinguished professor emeritus of the State University of New York in Buffalo, William H. Tallmadge, may have been shaped by years of study in American folk music history. For me, the recognition of a song I first heard and learned when I was knee-high to a crawdad was instantaneous. Perhaps two or three bars into the video of Jamie Levac performing what he says is Harney & Biller’s “You’ve Been a Good Old Wagon,” I thought, “Wait a minute. That’s obviously “Frog Went a-Courtin’.” There’s been some mistake.”

Despite what seems to be a very obvious connection between “Frog Went a-Courtin’,” and “You’ve Been a Good Old Wagon,” Jane Keefer’s comprehensive catalog of folk music, Folk Music Index to Recordings, disagrees. The index lists 15 related titles and 7 related melodies for “Crawdad,” including “Wagon” (also identified by Ms. Keefer as “The Wagon,” by Ben Harney), and 9 related titles (not minor spelling variants) for “Frog/Froggie Went A-Courting,” yet, according to Ms. Keefer, they have no related titles or melodies in common.**

On the other hand, 1940s Asch recordings of “Crawdad” and “Froggie Went a-Courtin'” by Woody Guthrie*** (videos included in the footnote) sound like recordings of essentially the same song, the principle difference, apart from the dissimilar lyrics, lying in the respective tempos at which they are played.

The Harney & Biller Good Old Wagon lyric as provided by Joe Offer in a Mudcat Café thread:

______________

I was standing in a crap game doing no harm, baby!

When a copper grabbed me by my arm, honey!

Took me down to the jailhouse door,

Place I never had been before, I was run in.

[Chorus]

No more will I buy my sweet thing pork chops!

And hear her lily lips go flip flop!

The reason I’m in trouble ’bout my sweet thing

Is because this song to me she did sing:

“Goodbye, my honey, if you call it gone, darling!

Goodbye, my honey, if you call it gone, baby!

Goodbye, my honey, if you call it gone,

You’ve been a good old wagon but you done broke down; bye-bye.”

The judge asked me what had I done; baby!

Said standing in a crap game getting my gun, hot stuff!

The judge and jury said to me,

“You have killed three people in the first degree; no bail.”

_______________

The lyric provided by Joe Offer at Mudcat Café corresponds virtually exactly, the only differences being in capitalization and punctuation, to one found in a set of sheet music pages available at the New York Public Library Digital Gallery, here:

- “Good Old Wagon”, Harney & Biller (1895) NYPL Digital Gallery, 4 pages (front and back covers missing)

A transcription of the lyric sung by Harney in the Gordon recording has been published in the article at the Library of Congress website (loc.gov) cited above, under the title

Variants of some of the lines in the lyric of the 1895 sheet music are sung by Harney in the Gordon recording. The last line of the final two sections of Gordon’s recording of Harney performing “Good Old Wagon,” which goes “A-this mornin’, this evenin’, so soon,” suggests its connection, lyrically, to the traditional songs “This Morning, This Evening, So Soon” and “Tell Old Bill.” A recording of the latter by the Kingston Trio was released under the title “This Mornin’, This Evenin’, So Soon” on their 1960 album String Along.

Raymond’s Folk Song Page, says of “Crawdad” and related songs:

This song from the Southern States of the U.S. grew out of African-American blues [see “Not Blues” text box above] combined with white American children’s play songs. There are a number of variations, such as This Morning, This Evening, So Soon, Sweet Thing, How Many Biscuits Can You Eat? and What Ya Gonna Do?, as sung by Josh White, for example.

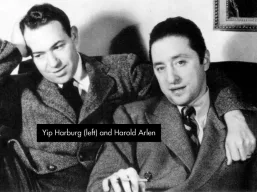

The aforementioned William H. Tallmadge article, “Ben Harney: The Middlesborough Years, 1890-93,” is my source of the sheet music cover (see above, top) which credits “Harney & Biller” as the songwriters, and features an illustration of the two. “Good Old Wagon” is a major focal point of the piece. There are pages devoted to the song’s possible folk roots, to it’s relationships with specific folk songs of the Appalachian Mountains, and to an appended stop-time stick dance created and performed by Harney which the author finds particularly noteworthy.

(above) from the article “Ben Harney: The Middlesborough Years, 1890-93,” by William H. Tallmadge, in the journal American Music, Volume 13, No. 2 (Summer 1995), p. 174

On pages 173-174 the author describes the process of getting Harney’s song, which he had brought with him “in his head and in his fingers” when he went to Louisville in 1893, onto paper. The account is supplemented with speculation by the author as to the extent of Biller’s contribution. Tallmadge suggests that Biller’s name may have been added because he was a well-known musician, and perhaps also in return for helping to get it published sooner. Biller was hired by the publisher, Bruner Greenup (of Greenup Music Company of Louisville Kentucky) to transcribe what Harney played and sang. Tallmadge quotes from an 1899 interview with Greenup:

Harney had no more idea than a monkey how to write rag time, though he could play it and sing it, perhaps, better than anyone has yet succeeded in doing…

Greenup goes on to explain that numerous “more or less famous” composers were called in to work on the task of getting Harney’s tune on paper, yet one by one they gave up in frustration, reporting that the job was too difficult. Finally, they took the song to John Biller, the musical director for Macauley’s Theatre, which was, according to Wikipedia, the premier theatre in Louisville during the late 19th and early 20th century. After perhaps 500 playings (Greenup’s estimate) by Harney, Biller was able to get the song on paper sometime in 1893.

Greenup goes on to explain that numerous “more or less famous” composers were called in to work on the task of getting Harney’s tune on paper, yet one by one they gave up in frustration, reporting that the job was too difficult. Finally, they took the song to John Biller, the musical director for Macauley’s Theatre, which was, according to Wikipedia, the premier theatre in Louisville during the late 19th and early 20th century. After perhaps 500 playings (Greenup’s estimate) by Harney, Biller was able to get the song on paper sometime in 1893.

I haven’t read the entire piece yet, which might provide some explanation, but it strikes me as rather odd that after such a great expenditure of effort to get the song on paper it was not published by Greenup until over a year later, in 1895. I wonder, also, if and how the author reconciles the claims that Harney had no clue as to how to transcribe ragtime, and that numerous “more or less famous” composers failed in their attempts to accomplish the task in this case, with the opinion that Biller’s contribution might have been negligible, if the music was indeed written down in 1893 by none other than Biller. Is it plausible that Biller merely recorded note for note what he heard Harney play, with every dynamic modulation, articulation, ornament, etc. precisely rendered into musical notation?

According to some biographies of Ben Harney, the style in which he wrote led many contemporaries to believe he was a black man. The error was still being repeated decades after his death. In a post within the blog Locust St., titled Elite Syncopations, 1900-1901, while commenting upon a cylinder recording by Len Spencer of “You’ve Been a Good Old Wagon,” the author notes that even Eubie Blake was certain that Harney was black, and that he evidently convinced Alec Wilder of the same:

_____________________________

* Regarding the date of the recording of Ben Harney singing Good Old Wagon, made by Robert Winslow Gordon, the aforementioned Library of Congress article says,

It is not known when or where Gordon recorded him, but an indistinct announcement on one of the five cylinders which he made seems to place the session on September 9, 1925, about a month before Gordon’s first North Carolina recordings of Lewey and Noell.

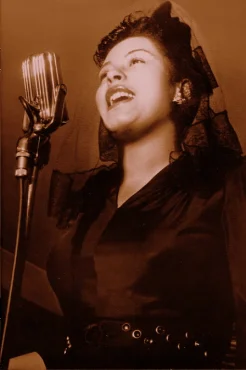

The blues song “You’ve Been a Good Ole Wagon” first recorded by Bessie Smith in 1925 (Columbia 14079-D, c/w “Dixie Flyer Blues”) is an unrelated number, with a different history. I mention this because a lot of folks are confusing them on the internet. Some are up at arms that Harney is not credited for the unrelated Smith song. If there’s any relationship between the music or lyric of Harney’s newfangled 1890s twist on “Frog Went a-Courtin’ ” and the Bessie Smith song, beyond the title, I haven’t detected it.

** Links to selected titles in Jane Keefer’s Folk Music Index to Recordings:

- Frog Went A-Courting

- Crawdad Song

- Sweet Thing

- This Morning, This Evening, So Soon – I — No author given. Listed as related to “Wagon” (Ben Harney), as well as to Crawdad (Song), and Policeman #1

- The Wagon (also identified by Ms. Keefer elsewhere as “Wagon”) — The song is credited by Ms. Keefer to Ben Harney, and she’s evidently referring to the song “You’ve Been a Good Old Wagon But You Done Broke Down,” but doesn’t mention that title or anything like it. According to Keefer, “This Morning, This Evening, So Soon” is related to “The Wagon,” and both are related to “Crawdad.”

- key to abbreviations

*** Woodie Guthrie recordings of “Froggie Went a-Courtin'” and “Crawdad Song”:

Froggie Went a-Courtin’ — from Buffalo Skinners: The Asch Recordings, Vol. 4 (1), (2), recorded in New York, NY, between 1944 and 1949

musicians for the sessions (from http://www.woodyguthrie.de/discog3.html):

musicians for the sessions (from http://www.woodyguthrie.de/discog3.html):

- Woody Guthrie (vocals, guitar, fiddle, mandolin, harmonica)

- Cisco Houston (vocals, guitar)

- Bess Lomax Hawes (mandolin)

- Sonny Terry (harmonica)

- Leadbelly (vocals, guitar) on “Stewball” (Version 2)

_________________

.

Crawdad Song — from Muleskinner Blues: The Asch Recordings Vol. 2 (1), (2), recorded in New York, NY, between 1944 and 1947

musicians for the sessions:

- Woody Guthrie (vocals, guitar, mandolin, fiddle)

- Cisco Houston (vocals, guitar)

- Butch Hawes (guitar)

- Bess Lomax Hawes (mandolin, background vocals)

- Pete Seeger (banjo)

- Sonny Terry (harmonica)

_____________

- lyric (transcribed by doc, 30 Nov 2013)

.

Of “Crawdad Song,” SecondHandSongs.com says:

Folksong originating in the southern United States and first published in a collection of songs in 1917 by Cecil Sharp. This song is apparently a variation of an older traditional work, “Sweet Thing”, which is of African-American origins. “Crawdad Song” is collected as number 4853 in the Roud Folksong Index.

- See my page Crawdad Song — selected recordings, 1933-1967 for additional recordings of “Crawdad Song,” aka “The Crawdad Song,” “Crawdad Hole,” Crawdad,” “You Get a Line and I’ll Get a Pole,” etc. SecondHandSongs.com identifies an October 1929 recording by Honeyboy & Sassafras as the first recording of the song. However, I haven’t included recordings of the song made prior to 1933 in the page, under any of the aforementioned titles, because I haven’t yet found any. My “Crawdad Song” page includes recordings of the song under various titles by the following artists:

- Lone Star Cowboys — recorded on 5 August 1933

- Jim Lewis Lonestar Cowboys — recorded on 24 September 1937

- Leroy Martin and unidentified performers (vocals) — recorded on 21 May 1939

- Mrs. Vernon Allen — recorded on 16 August 1940

- Woodie Guthrie — recorded between 1944 and 1947

- Al Clauser and his Oklahoma Outlaws — 1947(?)

- Lulu Belle & Scotty — c.1950

- Evelyn Knight and Red Foley — recorded on 28 November 1950

- Smokey Hogg — recorded on 9 January 1952

- Big Bill Broonzy — four recordings, three of them variously dated within the span 1953-1957, the other undated

- Sam Hinton — released in 1957

- The Goldenaires Choir — released in 1959

- Brownie McGhee and Sonny Terry — recorded in 1961; released in 1978

- Flatt & Scruggs with the Foggy Mountain Boys — television performance, broadcast in 1962

- Doc Watson, Clint Howard, and Fred Price — recorded in April 1962

- Doc Watson, Clint Howard, and Fred Price — recorded in 1967

_____________________

Selected recordings of some related songs

Whatcha Gonna Do When Your Licker Gives Out?

Fiddlin’ John Carson — possibly from the 17 December 1929 recording issued on the 10-inch 78 rpm single Okeh 45434, as the B-side of “Sunny Tennessee”

.

Sugar Babe

BluegrassMessengers.com, in its pages on each of eleven different versions of “Sugar Babe” (e.g. Version 1: Sharp, 1917) among its collection of fiddle tune lyrics, includes the following titles in it’s list of related songs:

“Baby Mine,” “Crawdad (Song),” “New River Train,” “I’m Going Back to Jericho (Mexico),” “This Morning, This Evening, So Soon,” “Policeman,” “Ain’t No Use in Working So Hard,” “How Many Biscuits Can You Eat,” “Going round the World Baby Mine/Banjo Pickin’ Girl,” “Gambler’s Song,” “Sweet Child,” “What You Gonna Do?” “Sweet Thing,” “Good Times,” “Crow-Fish Man,” “Honey Babe,” “Pittsburgh Town,” “Pittsburgh,” “Susie,” “Alice Brown”

From the “Notes” section of each “Sugar Babe” version page at BluegrassMessengers.com (bold added):

The song, Sugar Babe, is closely related to “Crawdad Song” (You get a line I’ll get a pole). The first printed version is a popular song “Baby Mine” from the late 1800’s. The song form used in “Baby Mine” published in 1874 as “Baby Mine” with words by Charles Mackay and music by Achibald Johnson is similar to the Captain Kidd/Froggy Went A-Courtin’ family of songs.

Lulu Belle & Scotty — 1935

The video provider attaches the following informaton:

** 1st Recording Session**… Recorded 30 October 1935 Furniture Mart Building, 666 Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, IL — Lulu Belle Wiseman [vcl], Scotty Wiseman [vcl/gt/banjo] …MYRTLE ELEANOR COOPER (From Boone NC 1913 – 1999)…And…SCOTT GREENE WISEMAN (From Ingalls NC 1909 – 1981)…Married in 1934…Very Popular & Famous Duo From 1934 to 1958…”Scotty” Wrote The Famous Country Classic “Have I Told You Lately That I Love You”

.

Sugar Babe — field recordings, 1939

John Lowry Goree (vocals) — recorded at his home in Houston, Texas, on 12 April 1939, by John and Ruby Lomax

.

Sims Tartt, Mandy Tartt, Bettie Atmore (vocals with tapping) — recorded on the porch of the home of Mr. & Mrs. W.P. Tartt, Livingston, Alabama, on 30 May 1939, by John Lomax

.

The lyric sung in the above recording:

N___ and the white man playing the seven-up, sugar babe

N___ and the white man playing seven-up, sugar babe

N___ and the white man playing seven-up

N___ win the money and scared to pick it up, sugar babe

I got a wife and a sweetheart too, sugar babe

I got a wife and a sweetheart too, sugar babe

I got a wife and a sweetheart too

Wife don’t love me but my sweetheart do, sugar babe

The words in the first section are obviously related to lines such as the following found in versions of the traditional “Limber Jim” songs:

N___ an’ a white man playing seven-up,

White man played an ace, an’ n___ feared to take it up

sources:

- book: Songsters and Saints: Vocal Traditions on Race Records, by Paul Oliver, 1984, pp. 105-106

- N**** and the White Man — The Traditional Tune Archive

- Origin: Limber Jim – The Mudcat Café

- Limber Jim (version 1), (2), (3), (4) – BluegrassMessengers.com

- According to BluegrassMessengers.com:

- The Limber Jim Songs originated from various 1800 minstrel song adaptations of the “Froggie Went a Courting/Martin Said To his Man” songs including the “Kemo Kimo” songs, “Kitty Alone” songs and “Goodbye Liza Jane” songs.

- According to BluegrassMessengers.com:

- Seven Up (version 1), (2) – BluegrassMessengers.com

________________________

How Many Biscuits Can You Eat

Coon Creek Girls — broadcast date (TV) and other info to be provided ASAP

.

Old Aunt James

Merle Haggard performs a relative of “Frog Went a-Courtin'” and “Crawdad,” possibly titled “This Morning, This Evening, So Soon” (date and location unknown) — It’s difficult to make out some of the words. The repeated phrase in the first section seems to be “Picked my cotton in a ten yard sack.” In the second section, unless my ears deceive me, Haggard seems to be repeatedly referring to someone or something called “Old Aunt James.” The word “Aunt” is pronounced such that it rhymes with “saint.” Here’s my transcription of the section of the lyric that focuses on “Old Aunt James”:

Old Aunt James spouted happily this morning

Old Aunt James spouted happily this evening

Old Aunt James spouted happily

But my voice it was tight like that

This morning, this evening, so soon

Keyword searches combining the title “This Morning, This Evening, So Soon” and “lyric” typically point to the lyric of the traditional song “Tell Old Bill,” which has “This Morning, This Evening, So Soon,” and similar variants, as an alternate title, and which includes that phrase in its lyric. However, all versions of “Tell Old Bill” that I’ve heard (Dave Van Ronk, Kingston Trio, Chad Mitchell Trio, for example), are quite different melodically and rhythmically than any versions of “Frog Went a-Courtin'” or “Crawdad” that I’m aware of, and unlike the song performed here by Merle Haggard, although the basic structure is similar. None of my searches have uncovered a lyric resembling the one sung by Haggard in this performance except with respect to the phrase “This Morning, This Evening, So Soon.”

With regard to “Old Aunt James,” see the reference to the alternate lyric line beginning with the similar “Old Aunt Jemima” in the “Description” of the “Back to Jericho” digital entry at fresnostate.edu (from the California State University, Fresno, digital Traditional Ballads Index). The same “description” is given in a slightly modified form in the Notes section of BluegrassMessengers.com’s “Back to Jericho,” and “I’m Goin’ Back to Jericho” pages.

___________________________

As on any Songbook page or post, comments may be added below. See also relevant comments in the Songbook survey page “1890-1899 selected hits and standards,“ which were posted before this page was created and the “You’ve Been a Good Old Wagon But You’ve Done Broke Down” feature was relocated from that page to this one.

Jan 28, 2017 @ 22:40:43

Hi, the “Crawdad Song”/”This Morning This Evening So Soon”/etc. family isn’t what’s generally considered blues music. Those types of songs were very popular as of the 1890s, and when people like W.C. Handy were asked about early blues, they very rarely brought those songs up, because blues music was thought of as different (more like “Joe Turner” and “Poor Boy Long Ways From Home”). Alan Lomax did ever categorize the crawdad song as a blues, but over the years he said just about anything.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Jan 30, 2017 @ 15:10:33

Hi,

I agree with you, and I don’t think anyone would classify it as blues today. I suspect that you’re referring to the following paragraph from this page in which I cite Talmadge, p. 181, where he had quoted from something that Lomax had written regarding the song family (bold added):

Second, in an article in the journal American Music, in Volume 13, No. 2 (Summer 1995), titled “Ben Harney: The Middlesborough Years, 1890-93,” by William H. Tallmadge (p. 167ff.), on pages 180-181 the author points out African-American folk blues (“common in the Appalachian Mountains”) sources of Harney’s “Good Old Wagon,” noting similarities to “Sugar Babe,” “Sweet Thing,” and “Crawdad Song,” and quotes John and Alan Lomax on the adoption of the Negro blues “Sweet Thing” by white banjo and guitar pickers to the extent that “today it can be heard wherever a hillbilly unlimbers his git-box” (p. 181).

The Lomax quote in Talmadge, p. 181, does use the term “Negro blues” in reference to “Sweet Thing,” specifically. Having not read much of Lomax, I don’t know if such usage was typical of his writings, but I’ll try to include in the relevant paragraph some explanation regarding the fact that the application of the term blues to this song would be irregular by today’s standards. Thanks for the help.

Regards,

doc

LikeLike

Sep 04, 2019 @ 17:08:48

“by today’s standards” Hi, the issue isn’t today’s standards vs. standards of an earlier time; as of 1910 the idea of quote “blues songs” was becoming increasingly popular, to describe folk songs in which the word “blues” had only become popular (among folk musicians, and no one else yet then) in the lyrics in about 1905, and both the blues musicians of about 1910-1930 and the earliest blues researchers were familiar with the “Crawdad” family and about how long ago it had been really popular and didn’t call it blues music because it preceded the blues songs about “blues” by many years and wasn’t very similar to them. Alan Lomax was an eccentric.

Best, Joe Scott

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sep 05, 2019 @ 15:12:29

Joe,

Ahh, thanks for the clarification on that. I’ve updated the “Not Blues” text box and revised other portions of the page accordingly. Thanks much for the help, and don’t hesitate to let me know if you find any other errors.

Regards, doc

LikeLike

Sep 06, 2019 @ 15:16:04

I may change the “Not Blues” text box to a footnote, since after revision it only refers to a couple of phrases in the paragraph which precedes it.

LikeLike