You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Gavin Evans/Retna: Front & back<br />

cover, 89; Mark Allan:122t; Joel<br />

Axelrad/Retna:79b; Brian Aris:<br />

147tr; Clive Arrowsmith/Camera<br />

Press:120; Glenn A. Baker/<br />

Redferns: 79r; BBC: 64br, 147b;<br />

Brendan Beirne/Rex: 6; Edward<br />

Bell: 128; Paul Bergen/Redferns:<br />

153tl; Peter Brooker/Rex:136t;<br />

Larry Busaca/Retna:153c; James<br />

Cameron/Redferns:101tc; George<br />

Chin/Redferns:152; Corbis: 54b;<br />

Fin Costello/Redferns: 106b;<br />

Courtesy of Crankin’ Out Collection:<br />

11, 13b, 18cl&b, 27bl, 31c, 33, 49, 5<br />

5tr&br, 59r, 64cl, 65, 66, 67, 83tl, 94<br />

br, 95bl, 112t, 118b, 142tl,<br />

148lt&b, 149, 154tl&r; Bill Davila<br />

/Retna: 136l; Debi Doss/Redferns:<br />

16br; EMI:36t, 37, 139t; Mary<br />

Evans Picture Library: 51t&b, 100c,<br />

147tc&bl; Chris Floyd/Camera<br />

Press:158; Chris Foster/Rex: 43l,<br />

69t; Ron Galella: 55bl; Guglielmo

Galvin:29; Harry Goodwin:34r, 35tr,<br />

c&bl, 73r, 107cl, 118l; Alison Hale/<br />

Crankin’ Out: 112b; Dezo Hoffman/<br />

Rex: 4, 6, 15, 19, 97t; Dave Hogan/<br />

Rex: 150; Hulton Getty:32t, 55tl,<br />

92, 108b, 114tl, 125br, 127, 133c,<br />

141ct; Mick Hutson/Redferns:21br;<br />

Nils Jorgensen/Rex: 34tc, 135;<br />

AndyKent/Retna:9, 111, 114c, 125c;<br />

Jak Kilby/Retna:10, 44t; King<br />

Collection/Retna:1; John Kirk/<br />

Redferns: 70b; Christian Koller/<br />

Crankin’Out:154c; Jean Pierre Leloir<br />

/Redferns: 34b; London Features<br />

International:1, 3, 4, 6, 7, 9, 10, 12, 1<br />

4t, 16tr, 20, 21tl, c&cr, 22t, 34tl&c, 5<br />

3tl&br, 54l&br, 64b, 69b, 73t, 74, 75<br />

br, 81, 82bl, 84, 85t&bl, c&t&br, 91br,<br />

103, 106l, 107tl&r&cr, 108tl, 109,<br />

110, 111c&b, 119, 125tr&bl, 129,<br />

131b, 132b, 134, 137, 139b, 140cr,<br />

141bc, 142bl&r, 143, 144, 145,<br />

146b, 151, 154b, 159bl; Doug<br />

McKenzie: 26, 27br, 36tl; MEN<br />

Syndication; 21tr; Pearce<br />

Marchbank:100/101b; Robert<br />

Matheu/Retna: 148t; Jeffrey Mayer:<br />

153tr; Catherine McGann, 155;<br />

Mirror Syndication Int: 57,<br />

108cl; Keith Morris/Redferns:79t;

© MTV Europe: 140bl; G. Neri/<br />

Sygma:126tl; Michael Ochs<br />

Archive/Redferns: 80t, 106cl, 156;<br />

Frank W. Ockenfels III: 54c; Alex<br />

Oliveira/Rex: 51c; Terry O’Neill:<br />

98t&bl, 102, 146t; Denis O’Regan/<br />

Idols: 55t; Scarlet Page/Retna:<br />

48b, 130; PA News:159tr; Courtesy<br />

of Penguin Books: 146r; Kenneth<br />

Pitt: 5, 44br, 45, 48l, 52; Pictorial<br />

Press:1, 3, 9, 14b, 36cr&b, 40, 42b,<br />

43r, 46tc&r, 47, 48tr, 53cr, 54t, 56t,<br />

60, 61t, 80r, 82tc, 83bc&r, 87tl,<br />

88tr, 99, 104tr, 114tr, 115, 133r, 14<br />

0bc, 141br; Photofest/Retna: 6,<br />

114bl; Barry Plummer: 46br, 87b,<br />

117b; Pat Pope/Rex:155; Neal<br />

Preston/Retna:139c, 140c, 148r;<br />

Michael Putland/Retna:6, 73l; RCA:<br />

118r, 121l, 126b; David Redfern:<br />

23; Redferns: 35tl, 105; Lorne<br />

Resnick/Retna: 9; Retna:108tr,<br />

141r; Rex Features: 9, 10, 22b, 27t,<br />

28bl, 42l, 50rt&b, 55b, 76, 82tl, 83t<br />

r, 83bl, 85t&bc, 86, 88br, 96, 97bl,<br />

100tr, 104b&l, 107bl, 116, 117t,<br />

121cr, 131t, 136bl, 138, 141c, 146cl,<br />

160; Ebet Roberts/Redferns:78b;<br />

Copyright © Mick Rock; 1, 16tl&c,<br />

38, 39, 42t&r, 68, 71, 72, 73b, 75l,<br />

77, 78tl, 87tr, 90, 93, 94t, 95t, 113,<br />

132t, 133tl&b, 140cl, 141t;<br />

Photograph by Ethan A. Russell<br />

copyright © 1972-2000: 106tr;<br />

Nina Schultz: 122b; Wendy

Smedley/Crankin’ Out: 112c; Steve<br />

Smith/Crankin’ Out:153br;<br />

Snowdon/Camera Press: 123, 124;<br />

Bob Solly Collection: 32b; Ray<br />

Stevenson/Retna:10, 4144bl,<br />

46bl&c, 53cl, tc, tr&bl, 59b, 61b,<br />

82bl; Masayoshi Sukita: 17, 91b,<br />

112bl, 148c; Charles Sykes/Rex: 8;<br />

Artur Vogdt: 101c; Wall/MPA/Retna:<br />

157; Chris Walter: 91t; Brian Ward:<br />

2, 63, 70t, 75t; Barry Wentzel: 140br;<br />

Kevin Wisniewski/Rex:159c;<br />

Richard Young/Rex: 31cb, 94bl, 31cb, 94bl,<br />

95br, 139br, 142tr, 159br.

At manager Ken Pitt’s flat, London. 1967. <strong>Bowie</strong> renn<br />

embers: “At th is time I was wondering whether I WAnted<br />

to be a serious, mime or whether I should carry on with<br />

music. That’s an incredible top.” Pitt: “It was an Arabic<br />

bolero from Palestine, and belonged to my mother.”

Amsterdam, 1977. “I think I have a certain vocabulary<br />

that, however much I change stylistically, there is a real<br />

core of imagery. I don’t see any abrupt changes in what<br />

I’ve done.”

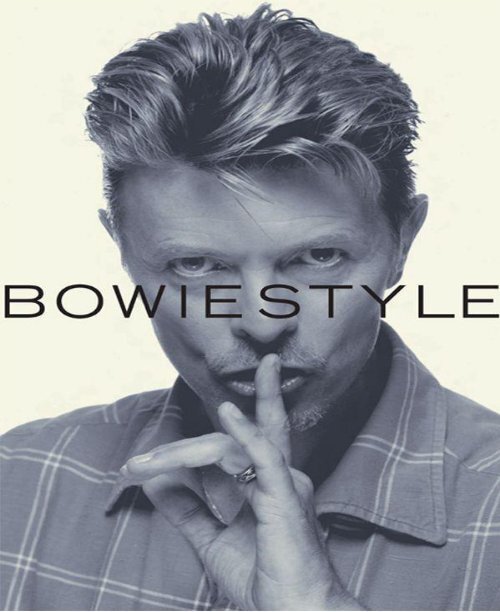

Only One Paper Left. New York, 1997, wearing Paul<br />

Smith: “I like to dress well, but it’s not something on which<br />

I felt my reputation should be built,” says <strong>Bowie</strong>.

An impeccably groomed Mod and a Millennium<br />

Man technophile. A riot of sexual confusion and<br />

a tanned, uncomplicated symbol of Eighties<br />

wealth.<br />

For four decades, David <strong>Bowie</strong> has been<br />

rock music’s most conspicuous mannequin and<br />

creator of fabulous fads and fashions – and<br />

outlived them all.<br />

<strong>Bowie</strong>’s formative years were spent chasing<br />

trends, often adding idiosyncratic touches to<br />

elevate himself above the crowd. Hitting a<br />

creative peak between 1972 and 1976, he<br />

transcended street style by reinventing himself<br />

into a one-man spectacular, a cultural whirlwind<br />

whose series of alter-egos – Ziggy Stardust,<br />

Aladdin Sane, the Thin White Duke – were<br />

lapped up by his flamboyant and dedicated<br />

flock with unflinching devotion.<br />

To his critics, who saw only costume-changes<br />

and grand theatrical gestures, <strong>Bowie</strong> was a<br />

clothes-horse who’d fast-tracked to stardom on<br />

a tide of hype.<br />

The sneers came thick and fast: Mock Rock,<br />

Glitter Rock, Shock Rock, Camp Rock, even<br />

Fag Rock, each invoked with a resigned shake<br />

of the head. <strong>Bowie</strong> was an arriviste, an invented<br />

star with the airs and whims of a pampered<br />

mistress in the hat department at Harrods.

Yes, <strong>Bowie</strong>’s project was about style and<br />

presentation, egos and whims. But beneath the<br />

shiny exteriors, those seemingly empty<br />

gestures, that lust to be looked at, was a brilliant<br />

new rock aesthetic – with David <strong>Bowie</strong> as its<br />

ideologue and showpiece. His playful mix-andmatch<br />

style wasn’t applied only to the costumes.<br />

Irreverence and pastiche also informed his<br />

music. He’d take the simple flash of Fifties<br />

rock’n’roll, the artful primitivism of little-known<br />

American warp-merchants The Velvet<br />

Underground and Iggy Pop, and give them a<br />

singer-songwriterly sheen. His concept of ‘The<br />

Star’, which he’d discuss with Warholian<br />

ingenuity, came gift-wrapped in fiction and<br />

artifice.

David <strong>Bowie</strong> revolutionised how rock looked.<br />

But he also changed how we looked at stars,<br />

and how we listened to music. Prior to his<br />

spectacular arrival in 1972, rock aspired to<br />

impress musicologists and literary types.<br />

<strong>Bowie</strong>’s most enduring influence was to drag<br />

rock music back to where the fiercest debates<br />

centred on authorship, sexual identity and the<br />

blurring of high and low art, debates that were<br />

later united under the postmodern banner. Far<br />

from smothering rock with foundation cream<br />

and elaborate stage sets, <strong>Bowie</strong> liberated the<br />

form, prompting a whole new set of debates<br />

and extending its limits.<br />

<strong>Bowie</strong>’s “style” has always amounted to more<br />

than clothes, hair and cosmetics. <strong>Style</strong>, for<br />

<strong>Bowie</strong>, is inextricable from art. It is the books he<br />

reads, the paintings he buys, the films he<br />

watches. It’s also bound up in the way he sees<br />

himself and how he lives his life. It is less a flight<br />

from reality than an entire way of life; that’s what<br />

makes him so fascinating. Anyone can adopt a<br />

series of guises in the name of art and build a<br />

stadium career out of it. In fact, many do. But

ultimately, <strong>Bowie</strong> is less about trappings and<br />

more about confronting the traps that seek to<br />

limit human potential. That quest has taken him<br />

from Beckenham to Babylon, from playful<br />

melodramas to the brink of insanity and death.<br />

The point of this book is not to repeat the<br />

details of <strong>Bowie</strong>’s musical career, which have<br />

been documented many times (though rarely<br />

with the thoroughness and insight of Peter and<br />

Leni Gillman’s Alias David <strong>Bowie</strong>, published in<br />

1986), but to explore his various stylistic guises<br />

in the context of their musical and cultural<br />

backdrops.<br />

<strong>Bowie</strong><strong>Style</strong> provides the signposts to every<br />

transformation, looks at the influences and the<br />

icons that helped shape them, and the debates<br />

and the controversies that each inevitably<br />

provoked.

As the vampirish 18th century aristocrat, John<br />

Blaylock, in The Hunger, Luton, 1982.

SHAPING UP<br />

As early as 1962, <strong>Bowie</strong> was behaving pseudonymously,<br />

styling himself Dave Jay during his year with supper-club<br />

combo The Kon-rads. The name was inspired by Peter Jay and<br />

The Jaywalkers, who, according to <strong>Bowie</strong>, were only one of two<br />

British bands “that knew anything about saxophones.”

David Jones at 18 months, at his parents’ home in Brixton.<br />

David <strong>Bowie</strong>’s earliest ventures into style conform<br />

closely to a textbook reading of post-war<br />

subcultural fashions. As David Jones, he<br />

developed a youthful passion for rock’n’roll,<br />

matured into jazz, then saw a role for himself in the<br />

burgeoning rhythm and blues movement. He grew<br />

his hair, blossomed into a Mod peacock then,<br />

having rechristened himself David <strong>Bowie</strong>, adopted<br />

the pose of a sophisticated Europhile.<br />

Unfortunately, there was little demand for such a<br />

creature in 1967, when hippie fashions dominated.<br />

Hopelessly wrong footed, David licked his wounds<br />

for several months before coming on as Bob<br />

Dylan-style folkie, albeit prettier and with an eye for<br />

a gimmick. That was the David <strong>Bowie</strong> the world first<br />

glimpsed in 1969 when ‘Space Oddity’, a faintly<br />

macabre interpretation of space travel, gave him<br />

his first taste of success.

1.1<br />

The Buddha Of Suburbia<br />

Suburbia spawned the British Rhythm & Blues<br />

boom. Punk rock’s greatest outrages were created<br />

there. And so, too, was David <strong>Bowie</strong>. Suburbia, a<br />

social space favoured by those ostriches of<br />

humankind who demanded a peaceful haven away<br />

from the grit and grime of urban life, is muchmaligned.<br />

But its simple ways and suffocating<br />

properness have proved time and again to be a<br />

valuable creative aid. Nothing arouses imaginations<br />

more, it seems, than the comfort zone marked out by<br />

net curtains and leafy cul-de-sacs.<br />

David <strong>Bowie</strong> was often profoundly embarrassed<br />

by his years spent in the comfort zone; it just wasn’t<br />

his style. Biographies usually describe him as “the<br />

boy from Brixton”, an altogether different social<br />

setting and one that suggests excitement, danger<br />

and streetwise urban glamour. Not that the young<br />

David Jones ever saw much of that: his family had<br />

quit south London by the time he was six, opting for<br />

a two-up, two-down in Bromley, Kent. That’s where<br />

David grew up before the allure of central London<br />

drew him away.<br />

St. Matthews Drive, Bromley, scene of <strong>Bowie</strong>’s Buddha Of<br />

Suburbia video shoot. He gave the shrubbery on the right a<br />

damned good kicking.<br />

Years later, in 1993, <strong>Bowie</strong> recalled the mental

landscapes of his youth with a cool, but hardly<br />

affectionate score for The Buddha Of Suburbia, a<br />

four-part television adaptation of Hanif Kureishi’s<br />

1990 novel. The project was tailor-made for him.<br />

Kureishi was a <strong>Bowie</strong> enthusiast who’d also plotted<br />

his escape while attending Bromley Tech; <strong>Bowie</strong><br />

could hardly have failed to recognise himself in the<br />

title, even if the book’s pop-seeker was based on a<br />

comtemporary of Kureishi’s, punk star Billy Idol.

The boy David. By 1953 the Jones family had swapped<br />

Brixton for Bromley - “the crummy bit,” <strong>Bowie</strong> recalled.<br />

It could be said that David’s first infant outfit, a<br />

nappy, later influenced the Sumo wrestler’s truss he<br />

wore on stage in 1973, but the building-blocks that<br />

helped shape his life, and the way he presented<br />

himself, had little to do with clothes. A likeable<br />

schoolboy and a popular Cub, with a keener interest<br />

than most for playing Cowboys and Indians, David<br />

was introduced to life beyond the comfort zone by<br />

his half-brother Terry. Terry, who was several years<br />

older, was a jazz enthuasiast with Beatnik ways.<br />

Often absent, his influence was primarily symbolic:<br />

he became David’s first idol whose wayward ways<br />

inevitably nourished his sibling’s later nonconformity.<br />

With Billy Idol, 1990. “It’s a sort of an amalgam of Billy, and<br />

Hanif’s impressions of what I probably was like. The silver suit, I<br />

think, was definitely me.” - <strong>Bowie</strong>’s thoughts on the Charlie Hero<br />

character in the BBC adaptation of The Buddha Of Suburbia.<br />

An outsider by virtue of his status as Peggy Jones’<br />

son from a previous relationship, Terry continued to<br />

exercise a strange hold on David’s imagination until<br />

his suicide in 1985. After he fell ill during the mid-<br />

Sixties and was diagnosed with schizophrenia, an<br />

illness that seemed to run in the family, <strong>Bowie</strong> was<br />

frightened yet fascinated. From the split personas of<br />

the Seventies to individual songs (one, ‘All The<br />

Madmen’, famously proclaimed that asylum inmates<br />

were “all as sane as me”), insanity became an<br />

enduring theme in <strong>Bowie</strong>’s work.<br />

David Jones’ fantasy life was further fuelled by<br />

America, a Technicolor funhouse stuffed with

gadgets and dream-factories, and rock’n’roll, which<br />

introduced a strange-looking, and even strangersounding,<br />

cast of miscreants into his life. He was<br />

nine in 1956, when rock’n’roll swept through Britain,<br />

but already old enough to plump for two of its most<br />

visually striking stars – mean’n’moody Elvis Presley<br />

and flamboyant Little Richard. Stars fascinated<br />

David. His father gave him an autograph book and<br />

took him backstage to meet Tommy Steele. David<br />

became hooked on fame.<br />

Aladdin nappies in Glasgow, 1973.

May 1964. Tonight, Matthew, I’m going to be Tommy Steele.

BOWIECHANGESPOP<br />

<strong>Bowie</strong>: “I was always accused of being cold and unfeeling.<br />

It was because I was intimidated about touching people.”<br />

“Sometimes I don’t feel like a person at all, I’m<br />

just a collection of other people’s ideas.” You<br />

wouldn’t have heard Mick Jagger, Bob Dylan, or<br />

Pete Townshend talking like that, but in June 1972,<br />

as Ziggymania was transforming him into the most<br />

discussed performer in pop, David <strong>Bowie</strong> was<br />

turning the concept of The Star on its head. It<br />

seemed as much about manufacture and<br />

manipulation as it was music.<br />

As the year began, <strong>Bowie</strong> had playfully predicted<br />

his own stardom, and then let his alter-ego, Ziggy<br />

Stardust, do all the hard work for him.<br />

The media gleefully dubbed him “The first rock<br />

star of the Seventies” knowing full well that the<br />

phrase had been concocted by <strong>Bowie</strong>’s manager.<br />

For 18 months, <strong>Bowie</strong>/Ziggy played the part of the

Superstar to the hilt. Only favoured journalists and<br />

photographers were given access to him; tours of<br />

Britain, America and Japan were conducted in a<br />

manner usually reserved for royalty; a phalanx of<br />

burly bodyguards surrounded <strong>Bowie</strong> at all times,<br />

while the attendant entourage travelled everywhere<br />

in limos. A mantra, “Mr. <strong>Bowie</strong> does not like to be<br />

touched,” was recited as if safe passage to a blissful<br />

afterlife depended on it. In emphasising the<br />

manufacture of stardom – using fictitious aliases,<br />

hype, and revelling in Hollywood-like plasticity –<br />

<strong>Bowie</strong> both uncovered and exploited the pop<br />

fantasy. The art was in the deconstruction; the<br />

outcome, as <strong>Bowie</strong> had always intended, was the<br />

real thing. What he couldn’t have predicted was the<br />

scale of his success; how, like the legends of Garbo<br />

or Valentino, the more remote and ‘false’ he<br />

became, the more his popularity grew. No one had<br />

reckoned with the repressed desire for old-style<br />

stars – glamorous, larger-than-life and endowed with<br />

unfathomable mystery.<br />

David <strong>Bowie</strong> wasn’t the first manufactured<br />

Superstar, but he was the first to make the ‘creation’<br />

an integral part of his enterprise. By using the device<br />

of an alter-ego, Ziggy Stardust, his bid for fame was<br />

both a quest and a goal. It is this distancing<br />

technique that lies at the heart of <strong>Bowie</strong>’s<br />

achievement. Pre-Ziggy rock artists (with the<br />

possible exception of Bob Dylan) were essentially<br />

one-dimensional men whose talents were measured<br />

according to the rules of poetic or musical<br />

competence. <strong>Bowie</strong> widened the rules to include<br />

visual elements, then bent them completely out of<br />

shape with a ‘knowingness and nothingness’ clause<br />

that dragged artifice into art. It was the end of<br />

innocence.

Greta Garbo and Rudolph Valentino, detached idols from<br />

cinema’s silent age.<br />

Lest we make the same mistakes as our less<br />

enlightened predecessors, the <strong>Bowie</strong> effect also<br />

impacted on musical style. The seeds of a potential<br />

crisis had already been sown by Marc Bolan, whose<br />

tinsel take on Fifties rock’n’roll had enraged<br />

progressive purists who suspected it was merely<br />

nostalgia via the back-door. As Melody Maker’s<br />

Roy Hollingworth commented in April 1972: “Is it your<br />

turn to tell the younger generation that they don’t<br />

know what real music is?” he asked readers.<br />

“The jacket was a French import made of nylon, though it<br />

had a leather look. He called this outfit his ‘James Dean plastic<br />

look’ and posed with that attitude: Ziggy Stardust, movie star,<br />

sighted in Hollywood, exposed for your pleasure.” -<br />

photographer Mick Rock.<br />

Bolan’s revival of the three-minute, three-chord<br />

song form indeed flouted rock’s two-decade<br />

advance. But was it so bad? Hadn’t the rush to<br />

become a respectable art form based on the<br />

archetypes of literature and classical music<br />

prompted a seepage of double-LPs where<br />

preposterous morality plays, often inspired by

Tolkien, would be played out to the sound of frenzied<br />

muso sparring.<br />

The “singing boutique” in action.<br />

Against this background, <strong>Bowie</strong>’s fleet-footed<br />

contrivance of an alternative rock canon – which<br />

included American sleazoid trashmongers Iggy Pop<br />

and The Velvet Underground, and Midlands<br />

miscreants Mott The Hoople – inevitably offended<br />

critical sensibilities. Like <strong>Bowie</strong>’s ersatz star pose,<br />

the effects weren’t really felt until punk.<br />

When <strong>Bowie</strong> made his grand entrée in 1972 with<br />

Ziggy Stardust, he played a cat-and-mouse game<br />

with one of rock’s central referents – identity.

As Ziggy became Aladdin Sane, and <strong>Bowie</strong> a<br />

“grasshopper” for whom role-play was a more gainful<br />

pursuit than the spurious notion of ‘finding himself’,<br />

the very foundations of rock shuddered. <strong>Bowie</strong><br />

declared he was gay, played the part of an<br />

androgyne from alien parts and forced audiences to<br />

confront their sexuality. The certainties came<br />

tumbling down. His concerts became multi-media<br />

extravaganzas incorporating mime, theatre and film.<br />

His songs, deceptively simple but skilfully<br />

administered, may even have been pastiches. David<br />

<strong>Bowie</strong> could be artfully highbrow or shamefully crass,<br />

a Romantic visionary or a postmodern bricoleur<br />

before such a thing was ever contemplated. One<br />

thing was definite: during 1972 and 1973 he altered<br />

the look, the sound and the meaning of rock’n’roll.<br />

For this achievement alone, he secured a vital place<br />

in history.

<strong>Bowie</strong> dressed in a quilted black plastic body suit, designed<br />

by Kansai Yamamoto, who commented: “<strong>Bowie</strong> has an unusual<br />

face. He’s neither a man nor a woman. There this aura of<br />

fantasy that surrounds him. He has flair.”

David’s father Haywood Stenton ‘John’ Jones, worked for<br />

children’s charity Dr. Barnado’s Homes. <strong>Bowie</strong> would<br />

occasionally sing for the orphans in the Sixties.

When you’re a boy, they dress you up in uniform. Bromley<br />

Tech’ was “the posh bit. I was a working class laddie going to<br />

school with nobs.”

A semi-autobiographical scene from Merry Christmas, Mr<br />

Lawrence, in 1982.<br />

John Jones was a firm, conventional man whose<br />

chief influence on his son was his lower middle class<br />

reserve. Years later, <strong>Bowie</strong> recalled his father’s “iron<br />

discipline” and the wartime mentality that scarred his<br />

parents’ generation. In a 1968 interview in The<br />

Times, he complained: “We feel our parents’<br />

generation has lost control, given up, they’re scared<br />

of the future… I feel it’s basically their fault that things<br />

are so bad.” The innocence and happiness of<br />

childhood is something <strong>Bowie</strong> revisited several<br />

times during his early adult life. There was nothing<br />

ambivalent about a line like “I wish I was a child<br />

again / I wish I felt secure again”, which he sang in<br />

1966. His first L P, released the following year, was<br />

virtually a lament to a vanquished childhood: “There<br />

Is A Happy Land,” he insisted, where “adults aren’t<br />

allowed”.<br />

Puberty broke the spell of universal brotherhood<br />

and encouraged competition and, in turn, personal<br />

development. At Bromley Technical High School<br />

(1958-63), the teenage David liked art and chased<br />

girls. More than that, the lanky schoolboy developed<br />

a compulsive need to stand out from the crowd, and<br />

test the bounds of popular taste. These two school<br />

photographs reveal the transformation. On the left, in<br />

1959, the pre-teen David, with his regulation haircut<br />

and smart uniform, looks every inch the model pupil.<br />

For the second (below), taken in 1962, his body is<br />

angled provocatively, his head crowned by a bizarre,<br />

space-age quiff, a thick blond streak added for<br />

dramatic effect. He’d become the classic teenage<br />

rebel, all attitude and self-consciousness.

Almost Grown. “He was always into a thousand things.<br />

David always wanted to be different, though in those days he<br />

was just one of the lads.” - life-long friend George Underwood.

”I didn’t mind a sense of elegance and style as a child, but I<br />

liked it when things were a bit off. A bit sort of fish-and-chips<br />

shop.”

I’M YOUR FAN<br />

<strong>Bowie</strong> celebrated his 50th birthday with an allstar bash at<br />

Madison Square Garden, New York, 1997.

On 9 January 1997, <strong>Bowie</strong> celebrated his 50th<br />

birthday (a day late) in front of a 20, 000-strong<br />

audience at New York’s Madison Square Garden.<br />

There was no Spiders From Mars revival. No Iggy<br />

Pop or Mick Jagger or Tina Turner. Instead, <strong>Bowie</strong><br />

surrounded himself with some of his sharper friends,<br />

like Sonic Youth, The Smashing Pumpkins’ Billy<br />

Corgan, Foo Fighters, ex-Pixie Frank Black and The<br />

Cure’s Robert “What do I do with this lipstick?”<br />

Smith. The only other old boy was Lou Reed.<br />

Sometimes, though, it suits the young pretenders to<br />

seek <strong>Bowie</strong> out…

Suede<br />

Twenty years later, the “I’m Gay… but then again<br />

maybe I’m not” strategy was revived by Suede’s<br />

Brett Anderson. It won Suede a few extra magazine<br />

covers, and secured the insatiable Anderson an<br />

audience with <strong>Bowie</strong> for an NME ‘summit meeting’<br />

and cover.<br />

Nine Inch Nails<br />

Trent Reznor’s pretty hateful noise machine hitched<br />

a ride on the US leg of <strong>Bowie</strong>’s Outsidetour which,<br />

by no coincidence, featured the NIN-influenced ‘Hallo<br />

Spaceboy’. Reznor has remixed a couple of <strong>Bowie</strong><br />

songs, ‘The Hearts Filthy Lesson’ and ‘I’m Afraid Of<br />

Americans’, and has taken to working with several of<br />

<strong>Bowie</strong>’s backing musicians.<br />

Morrissey<br />

Glam aficionado Morrissey shared a stage with<br />

<strong>Bowie</strong> in 1991 for a version of Marc Bolan’s<br />

‘Cosmic Dancer’, and coaxed Mick Ronson back to<br />

produce his 1992 album, Your Arsenal , which<br />

included the <strong>Bowie</strong>-esque ‘I Know It’s Gonna<br />

Happen Someday’, complete with ‘Rock’n’Roll

Suicide’-style coda. “David <strong>Bowie</strong> doing Morrissey<br />

doing David <strong>Bowie</strong>” was too good to miss, said<br />

<strong>Bowie</strong>, who promptly re-recorded the track for Black<br />

Tie White Noise.<br />

Nirvana<br />

David <strong>Bowie</strong>’s reputation received an unexpected<br />

boost when Kurt Cobain’s group of grunge stalwarts<br />

gave a sterling performance of ‘The Man Who Sold<br />

The World’ for an MTV Unplugged TV special in<br />

1993.<br />

Just a few months later, Cobain had, in his<br />

mother’s words, joined “that stupid club”, a real-life<br />

“rock’n’roll suicide”. Five years, that’s all he got.<br />

Placebo<br />

Panda-eyed Brian Molko has studied <strong>Bowie</strong>’s<br />

strategies closely. And he’s been generously<br />

rewarded with a studio collaboration, ‘Without You<br />

I’m Nothing’, plenty of namechecks, and a joint<br />

appearance with David <strong>Bowie</strong> on the 1999 Brit<br />

Awards show.

A rare publicity shot of The Kon-rads, circa 1963. “We wore<br />

gold corduroy jackets, I remember, and brown mohair trousers<br />

and green, brown and white ties, I think, and white shirts.<br />

Strange colouration.”<br />

By 1962, the Teddy Boy look already belonged to<br />

the previous decade, but stray remnants of the style -<br />

narrow tie, drainpipe trousers - could still earn<br />

reputations for 15-year-old boys. Already, styles<br />

were being mixed, and David’s winklepicker shoes<br />

and button-down shirts, both recent imports from<br />

Italy, were evidence of the emerging Modernist look,<br />

a sophisticated, aspirational style that contrasted<br />

with the Teds’ aggressive working-class stance.<br />

<strong>Bowie</strong> later enthused about the new breed to<br />

journalist Timothy White: “These weren’t the anorak<br />

Mods (who) turned up on scooters… They wore very<br />

expensive suits; very, very dapper. And make-up<br />

was an important part of it; lipstick, blush,<br />

eyeshadow, and out-and-out pancake powder… It<br />

was very dandified.”<br />

Chic, modern and highly individualistic, the Mod<br />

ethic proved instantly seductive to aspiring<br />

peacocks like David Jones and his mate, George<br />

Underwood. But their competitiveness sometimes<br />

strayed beyond fashion and music. An argument<br />

over a girl called Deirdre in 1962 ended when<br />

George walloped David in the eye, leaving him with

an indelible characteristic that even surpassed his<br />

left-handedness for marking him out as ‘different’ - a<br />

permanently dilated pupil in his left eye that leaves<br />

the impression that one eye is much darker than the<br />

other.<br />

The King Bees, 1964. George Underwood is on the far left.<br />

David claimed the other members were “some guys from<br />

Brixton I met in a barber’s shop”

The dilated pupil in <strong>Bowie</strong>’s left eye, the apparent legacy of<br />

a punch-up with pal George Underwood, may, some suggest,<br />

have actually been caused by an accident with a toy propeller.

INFLUENCES & HEROES: HOOKED<br />

TO THE SILVER SCREEN<br />

Influences and heroes play an enormous part in<br />

<strong>Bowie</strong>’s life and work.<br />

A born enthusiast, who can’t help but share his<br />

passion for little-known writers or new musical fads,<br />

<strong>Bowie</strong> virtually invented off-the-peg cultural capital<br />

single-handedly. Commodity fetishism? Perhaps.<br />

An empty display? Well, he does have a fast<br />

turnover rate, but that’s more likely a reflection of<br />

his thirst for new ideas.<br />

Films and film idols have provided <strong>Bowie</strong> with an<br />

endless source of material. He’s nicked a few titles<br />

for his songs, a few images for his album covers.<br />

He’s even made one or two memorable<br />

contributions to the silver screen himself.<br />

A Clockwork Orange<br />

Stanley Kubrick’s film of Anthony Burgess’s novel<br />

proved so disturbing that the director withdrew it<br />

from cinemas just a year after its release in 1971.<br />

Promoted as “the adventures of a young man whose<br />

principal interests are rape, ultraviolence and<br />

Beethoven”, the movie was plagiarised by <strong>Bowie</strong> for<br />

its look, its ‘nadsat’ (street slang), and its theme

music, Wendy Carlos’s Moog take on Beethoven’s<br />

‘Ode To Joy’, which was used to herald the Spiders’<br />

arrival on stage during 1972 and ‘73. The piece<br />

reappeared as intro music for <strong>Bowie</strong>’s 1990 Sound<br />

+ Vision tour.<br />

Un Chien Andalou<br />

Dead donkeys rest inside pianos. A woman,<br />

dressed in masculine-style attire, pokes at a<br />

severed hand. A cyclist inexplicably falls off his bike.<br />

Anonymous breasts are fondled. But before all this,<br />

a woman’s eye is opened and neatly slit with a razor.<br />

The film is Un Chien Andalou, a masterpiece of<br />

avant-garde cinema concocted by surrealist<br />

mischief-makers Salvador Dali and Luis Bunuel.<br />

Apart from the time Roxy Music supported him at the<br />

Rainbow, this 17-minute short – projected before his<br />

1976 Station To Station shows – is the best support<br />

act <strong>Bowie</strong>’s ever had. And, perhaps, the inspiration<br />

for that memorable “throwing darts in lovers’ eyes”<br />

quip.<br />

Metropolis<br />

Fritz Lang’s 1926 masterpiece of German<br />

Expressionist cinema, a futuristic study in glorious<br />

art deco, was brought to <strong>Bowie</strong>’s attention by<br />

Amanda Lear. After viewing the film, early in 1974,<br />

he devoured everything he could find on Lang and<br />

related subjects. Several years later, <strong>Bowie</strong> was<br />

poised to bid for the film rights, until producer<br />

Giorgio Moroder beat him to it. Metropolis, and<br />

another Expressionist classic, The Cabinet Of<br />

Doctor Caligari, provided the inspiration for the stark<br />

imagery of the 1976 stage shows.

<strong>Bowie</strong> playing the alien in Nic Roeg’s 1976 film, The Man<br />

Who Fell To Earth.

Bunuel and Dali’s surrealist short, Un Chien Andalou, with<br />

its controversial eye slitting shot, provided a shocking support<br />

act for <strong>Bowie</strong>’s 1976 tour.<br />

‘Wild Is The Wind’<br />

<strong>Bowie</strong> revived the title song of this 1957 George<br />

Cukor melodrama, starring Anna Magnani and<br />

Anthony Quinn, for Station To Station. However, he<br />

probably came to it via Nina Simone’s Sixties<br />

recording of the song, which he has cited as his<br />

favourite ever recording.

2001: A Space Odyssey<br />

Stanley Kubrick transformed an Arthur C Clarke<br />

story into a mesmerising cinematic acid trip in 1968.<br />

The denouement – a spaceman drifts into oblivion –<br />

was a clear inspiration for <strong>Bowie</strong>’s ‘Space Oddity’,<br />

which also owed some of its success to the space<br />

race that ended on July 20, 1969 when Neil<br />

Armstrong became the first man on the moon.<br />

‘Beauty And The Beast’<br />

Jean Cocteau’s magical interpretation of the fairy<br />

story was filmed in 1945 as La Belle Et La Bete<br />

(below). <strong>Bowie</strong> recorded his version for 1977’s<br />

“Heroes”.<br />

Richard Burton plays ‘Angry Young Man’ Jimmy Porter in<br />

the 1959 movie, Look Back In Anger. Mary Ure, left, and Claire<br />

Bloom, right, co-star.<br />

‘Starman’<br />

That chorus sound familiar? “It was actually meant to<br />

be a male version of ‘Over The Rainbow’,<br />

“confessed the man once described as a “Judy

Garland for the rock generation”. The song was<br />

made popular by Garland in the 1939 evergreen,<br />

The Wizard Of Oz (below).<br />

‘Look Back In Anger’<br />

This John Osborne play, a key Angry Young Man<br />

text, was filmed by Tony Richardson in 1959 and<br />

popularised the idea of the solitary male raging<br />

against his sorry lot.<br />

Lodger<br />

Roman Polanski’s 1976 movie, The Tenant, was a<br />

morbid study in paranoia and insanity, and a likely,<br />

though rarely acknowledged, source for the<br />

Lodgeralbum title.<br />

‘Dead Man Walking’<br />

Sean Penn directed and co-starred with Susan<br />

Sarandon in this Oscar-winning true story from the<br />

mid-Nineties.<br />

‘Seven Years In Tibet’<br />

Heinrich Harrer’s account of an ex-Nazi on the run<br />

from the Allies, who journeys to the mountains of<br />

Tibet where he befriends the Dalai Lama, provided<br />

an ideal launching-pad for a <strong>Bowie</strong> song.

1.2<br />

It’s A Mod, Mod World<br />

Wearing Chelsea boots and three-button suit with double<br />

back vent: “I didn’t really like the Teddy clothes too much. I liked<br />

Italian stuff. I liked the box jackets and the mohair. You could get

some of that locally in Bromley, but not very good. You’d have to<br />

go right up to Shepherd’s Bush or the East End.”<br />

Between 1963 and 1966, London became the<br />

style capital of the world. Galvanised by the<br />

resounding thud of the Beatles-inspired beat boom,<br />

Britain’s first post-war generation cast off the<br />

National Service mindset in favour of a riot of selfexpression.<br />

Carnaby Street was awash with<br />

boutiques, scooters roared down busy city streets<br />

and the state of the nation debate centred on the<br />

length of young men’s hair.<br />

David Jones, already on intimate terms with his<br />

bedroom mirror, was perfectly poised to join the<br />

cultural revolution. He was obsessed by stardom,<br />

taste and style which, in true Mod fashion, would<br />

change with the weather. His attention to such<br />

matters gave him his first taste of media controversy<br />

when, in November 1964, he was invited onto a<br />

television show to defend the right of young men to<br />

grow their hair. His first concern, though, was carving<br />

a niche for himself on the music scene.<br />

Unfortunately, it was the era for groups, so David<br />

was forced to throw in his lot with other musicians. It<br />

was a frustrating period for him, with success<br />

proving more elusive than he might have imagined.<br />

“I didn’t like riding scooters,” admitted <strong>Bowie</strong>. Though that

didn’t stop him having this one customised for promotional<br />

purposes years after the Mod boom.<br />

A newly peroxided Davie Jones with The King Bees<br />

performing ‘Liza Jane’ on BBC2’s The Beat Room, June 1964.

Portrait of a young man as an art buff. In satin trousers at<br />

manager Ralph Horton’s flat in 1966.

PAINTER MAN<br />

I Am A World Champion, 1977, (below). “In neither music<br />

nor art, have I a real style, craft or technique. I just plummet<br />

through, on either a wave of euphoria or mind-splintering<br />

dejection.”<br />

During the early Seventies, David <strong>Bowie</strong><br />

transformed rock by applying contemporary art<br />

concepts to a medium that lived in the shadow of<br />

19th century Romanticism. He compared himself to<br />

a Rosetti painting, name-dropped Andy Warhol to<br />

anyone who’d listen, and sought to elevate rock<br />

performance to the status of high art. <strong>Bowie</strong> even<br />

patronised Belgian artist Guy Peelaert, who was<br />

commissioned to paint the cover of the 1974 LP,<br />

Diamond Dogs.<br />

<strong>Bowie</strong> was an aesthete, for sure, but a practising<br />

fine artist? Not according to this quip made during a<br />

1973 interview: “When I was an art student I used to<br />

paint but when I decided I was no good at painting, I<br />

set myself to writing, to say the things I’d wanted to<br />

say through painting.” Times have changed; today,<br />

<strong>Bowie</strong> is as embroiled in fine art as he is in rock.<br />

He’s not only a patron, but a publisher, a critic and,<br />

most importantly, an exhibiting artist.<br />

His interest in painting was aroused by a school<br />

art teacher. Owen Frampton’s art classes<br />

encouraged freedom of expression, and David<br />

flourished under his master’s direction, obtaining a

are O-level pass in the subject. His artistic flair was<br />

also felt at home where he painted cave-like images<br />

on the walls of his bedroom.<br />

With 1976’s Head Of J.O., his portrait of Iggy Pop, Los<br />

Angeles, 1990 (below). In the early Nineties, <strong>Bowie</strong> renamed his<br />

song publishing company Tintoretto Music, after the Italian<br />

Renaissance painter.<br />

Frampton, whose guitar-playing son Peter was<br />

also destined for a musical career, helped David<br />

find his first job as a trainee graphic artist in a West<br />

End advertising agency. He lasted six months.<br />

Making teas and performing menial tasks killed off<br />

his enthusiam. Pop stardom, which would give him<br />

control and fame, proved far more appealing. When<br />

that failed, and he was taken under the wing of a new<br />

manager, Ken Pitt. <strong>Bowie</strong>’s enthusiasm for art was<br />

reawakened by Pitt’s enthusiasm for Aubrey<br />

Beardsley and the late Victorians.<br />

Paul McCartney’s <strong>Bowie</strong> Spewing, 1990 (right). David:<br />

“When you are an artist you can turn your hand to anything, in<br />

any style. Once you have the tools then all the artforms are the<br />

same in the end.”<br />

But the great revelation came when he discovered

Andy Warhol. Warhol worked with the shiny surfaces<br />

of consumer society, like soup cans and tins of<br />

Coke. But he also magnified modern horrors, like<br />

the electric chair, car crashes, the media’s desire to<br />

see grief. Even more intriguing was Warhol’s<br />

persona, as blank as a plain canvas. It was possibly<br />

his greatest work of all.

Fulham, 1995, with samples of his work (clockwise from<br />

left): Little Stranger, Metal Hearth And The Black Coat, 1993;<br />

The Crowd Pleasers, 1978; The Remember II, 1995; Ancestor,<br />

1995.

Portrait of the artist in four parts. 1996 Self Portraits,<br />

available from www.bowieart.com.

Walter Gramattè’s 1921 canvas, Selbstbildnis in Hiddensoe,<br />

was the partial inspiration for <strong>Bowie</strong>’s “Heroes” album sleeve.<br />

The more <strong>Bowie</strong> read about modern art, the more he<br />

realised that rock was still in the dark ages. Picasso<br />

and Dali had confounded audiences with sudden<br />

changes in style and flagrant self-promotion<br />

decades ago. Art had proved powerful enough to<br />

withstand the anti-art strategies of the Dadaists and<br />

Surrealists, whose visual time-bombs had<br />

threatened to make art irrelevant. All these issues<br />

thrilled <strong>Bowie</strong>, and helped shape the intellectual<br />

backdrop to his work in the early Seventies. <strong>Bowie</strong><br />

always doodled – Radio 1 producer Jeff Griffin<br />

remembers him sketching a Ziggy-inspired The<br />

Entertainer Who Is Shot On Stage during a 1972<br />

recording session. But it was while filming The Man<br />

Who Fell To Earth in 1975, when <strong>Bowie</strong> had time on<br />

his hands and a barren, New Mexico sagebrush<br />

desert to contemplate, that he began sketching in<br />

earnest. By the time of his 1976 tour, he carried a<br />

sketch-book everywhere. his thirst for art had<br />

become all-consuming. He continued to paint, buried<br />

himself in text-books and artists’ monographs,<br />

began investing in little-known contemporary works,<br />

and was a frequent visitor to the Brucke Museum Of<br />

Expressionist Art in West Berlin. Two paintings in<br />

the Brücke collection inspired album sleeves: Erich<br />

Heckel’s Roquairol provided the model for Iggy<br />

Pop’s engaging pose on his <strong>Bowie</strong>-assisted 1977<br />

album, The Idiot ; while the similarly-angular poise of<br />

Gramatté’s self-portrait was adopted by <strong>Bowie</strong> for<br />

his “Heroes” album. A third, Otto Mueller’s intense,<br />

eerily prescient Lovers Between Garden Walls (this<br />

was Berlin, remember), was an inspiration for the

title track. <strong>Bowie</strong>’s art aspirations – and connections<br />

– became more fully realised during the Nineties.<br />

In 1993, he joined the board of the quarterly<br />

magazine Modern Painters ; where he’s contributed<br />

articles and reviews on various subjects, including<br />

Tracey Emin, Julian Schnabel and Jeff Koons (with<br />

<strong>Bowie</strong>, above), African art and a 12, 000 word piece<br />

on Balthus. He’s courted the BritArt generation,<br />

particularly Damien Hirst, (above) with whom he<br />

collaborated on some ‘spin art’ (right). He is also a<br />

director of 21, a publishing company specialising in<br />

fine art books. Titles so far include artist/critic<br />

Matthew Collings’ Blimey! and William Boyd’s<br />

biography of fictitious artist Nat Tate.<br />

<strong>Bowie</strong> first exhibited a whole series of artworks in<br />

1994 when We Saw A Minotaur was included as<br />

part of Little Pieces From Big Stars, a fund-raising<br />

collection of celebrity art. In April 1995, The Gallery In<br />

Cork Street mounted his first one-man show, New

Afro/Pagan And Work 1975-1995, a retrospective<br />

that included Expressionist-influenced figurative<br />

work, sculptures and computer-generated wallpaper<br />

designs. The majority of the collection was sold (one<br />

piece fetched a respectable £17, 500), prompting a<br />

second show in Basle, Switzerland the following<br />

year. Since then, <strong>Bowie</strong> has become increasingly<br />

enthralled by computer-generated images, which he<br />

now sells via his <strong>Bowie</strong>Art website.<br />

With Balthus at the latter’s chalet in Rossiniere,<br />

Switzerland, June 1994.<br />

With Damien Hirst at Cork Street, London, April 1995.<br />

For all the talk of media cross-pollinisation, critics<br />

have found <strong>Bowie</strong>’s fine art aspirations difficult to<br />

take. Statements like “I’m a mid-art populist and<br />

postmodernist Buddhist who is casually surfing his<br />

way through the chaos of the late 20th century” are<br />

probably not the best way to mollify his detractors.<br />

According to his agent Kate Chertavian, these<br />

suspicions are misplaced: “I think his credibility<br />

grows with each year and each successful project<br />

that he does.” She maintains that his work will

endure, “partly because he is one of the first to cross<br />

mediums like this successfully.”<br />

Damien Hirst and David <strong>Bowie</strong>… beautiful, hello, spaceboy<br />

painting, 1995.

<strong>Bowie</strong> recently revamped The Crowd Pleasers as a unique<br />

postcard piece for a Royal College of Art exhibition where the<br />

identity of the artist is only revealed on the reverse after<br />

purchase. Price? Just £35<br />

“I wouldn’t have my hair cut for the Prime Minister, let alone<br />

the BBC,” declared defiant Davie in March 1965. With him is TV<br />

producer Barry Langford, who reignited the long-hair debate to<br />

publicise his new BBC2 show, Gadzooks!<br />

Before venturing into the cultish world of R&B, and

the dandified universe of the Mod, David cut his<br />

musical teeth with a local covers band, The Konrads.<br />

Early publicity shots show the group smartly<br />

turned out in matching suits and ties, the kind of<br />

budget sophisticate look favoured by the pre-pop<br />

dance combos. David, strikingly blond and with an<br />

immaculate DA (duck’s arse) hairstyle, was the<br />

band’s frontman and visual focus, despite being the<br />

most inexperienced member.<br />

By early 1963, he was sporting a fashionable<br />

Beatle cut, encouraging the band to consider their<br />

presentation (apparently he suggested they wear<br />

zoot suits or Wild West outfits) and writing his own<br />

songs. Clearly, he had outgrown the passé and<br />

formula-ridden Kon-rads. Instead, he began raiding<br />

Carnaby Street dustbins for expensive Italian castoffs,<br />

and threw his lot in with the hard-edged music<br />

emerging from the London clubs.<br />

Rhythm & Blues (R&B), a bi-product of the jazz<br />

scene, was the biggest musical undercurrent in<br />

1963, and a dominant commercial force over the<br />

next two years thanks to the success of groups like<br />

The Rolling Stones, The Animals, The Yardbirds and<br />

Them. More than a musical style, R&B was a<br />

mission; its followers were zealots, usually<br />

disaffected young men who envied the success of<br />

The Beatles and the Mersey groups, but regarded<br />

them with suspicion.<br />

In adopting the music, attitude and argot of the<br />

American black man, the white suburban blue boys<br />

occupied the cultural high ground. Beatle-mania was<br />

loveable, moptoppish and ubiquitous. R&B was its<br />

surly, shabbier cousin, who preferred to be on the<br />

outside looking in.<br />

For the next year or so, David Jones invested in a<br />

pair of casual trousers and waistcoat and immersed<br />

himself in R&B. Less concerned with debates about<br />

purism and ‘authenticity’ (he favoured the newer<br />

jazz/soul flavours over the founding fathers from<br />

Chicago and the Mississippi Delta), he fronted a<br />

succession of bands (Dave’s Reds & Blues, The<br />

Hooker Brothers) looking every inch the Brian Jones<br />

(Rolling Stones) or Keith Relf (Yardbirds) wannabe.

The Mannish Boys in Maidstone’s Mote Park, 1964: “It’s all<br />

criminals round there. It’s the only time in my life I’ve ever been<br />

beaten up. This big herbert just knocked me on the pavement,<br />

and proceeded to kick the shit out of me. I haven’t got many<br />

good memories of Maidstone.”<br />

After a couple of false starts, David joined The<br />

King Bees, whose lone 1964 single, ‘Liza Jane’, got<br />

lost amid the great R&B goldrush. The experience<br />

did allow him to indulge his passion for fashion,<br />

though, and as king of The King Bees, ‘Davie’<br />

augmented the standard waistcoat and high-collared<br />

shirt look with a bizarre pair of calf-length suede<br />

boots. The dandification didn’t stop there: he wore<br />

several rings, a brightly-coloured cravat and sported<br />

a layered haircut that virtually doubled the size of his<br />

head.<br />

Within months, this gnome-like apparition had<br />

been replaced by the full ‘Keith Relf’. The long blond<br />

bob was far more flattering to his chiselled features,<br />

framing his classic face in the manner of a Swinging<br />

Sixties ‘dolly bird’. It was a look that would have<br />

tested the patience of every hairdresser, and<br />

aroused the wrath of the spotty beer boys on every<br />

street corner.<br />

Now vocalist with The Manish Boys, David had<br />

been ‘made’ President of the International League<br />

For The Preservation Of Animal Filament, later the<br />

Society For The Prevention of Cruelty To Long-<br />

Haired Men, a publicity scam arranged by his agent.<br />

It got his name in the papers, complaining that<br />

“anyone who has the courage to wear his hair down<br />

to his shoulders has to go through hell”, and on<br />

television, where he told Tonight presenter Cliff<br />

Michelmore: “For the last two years, we’ve had

comments like ‘darling’ and ‘Can I carry your<br />

handbag?’ thrown at us and I think it has to stop.<br />

In one 1964 interview, David insisted, “I would<br />

sooner achieve the status as a Manish Boy that Mick<br />

Jagger enjoys as a Rolling Stone than end up a<br />

small-name solo singer.” With his next group, The<br />

Lower Third, he had it both ways, adding his name<br />

as the prefix. Impatient and still desperately chasing<br />

success, he modelled the group on The Who,<br />

hitching mid-Sixties Carnaby Street Mod imagery to<br />

a more metropolitan take on R&B. The group’s first<br />

single, ‘You’ve Got A Habit Of Leaving’, was a clear<br />

appropriation of The Who’s sound; they’d even<br />

roped in Who producer Shel Talmy for the session.<br />

As David’s pop modernist styles grew ever more<br />

flamboyant, his hipster strides, chisel-toed shoes<br />

and highly-cultivated (and lacquered)

Safely inside the BBC Television Centre, prior to performing<br />

“I Pity The Fool” with The Mannish Boys. Organist Bob Solly:<br />

“We all wanted to sing. We only let him join because (agent) Les<br />

Conn gave us the impression the person coming down was the<br />

black American blues singer, Davy Jones!”

INFLUENCES & HEROES: ALL THE<br />

OLD DUDES<br />

Mime artist Lindsay Kemp’s stage shows get ever more<br />

elaborate, but the thong remains the same.

Elvis Presley<br />

“I saw a cousin of mine dance when I was very<br />

young. She was dancing to Elvis’s ‘Hound Dog’ and I<br />

had never seen her get up and be moved so much<br />

by anything. It really impressed me, the power of<br />

music.” The 12-year-old David Jones told a schoolteacher<br />

that he intended to become “the British<br />

Elvis” – with whom he shared the same birthday, 8<br />

January.<br />

Terry Burns<br />

David’s elder half brother was handsome, imageconscious<br />

and, unlike his younger sibling, always at<br />

odds with the Jones family. He introduced David to<br />

beat books, jazz and philosophy, but his descent into<br />

schizophrenia, which became an enduring motif in<br />

<strong>Bowie</strong>’s work (most notably on ‘All The Madmen’<br />

and ‘The Bewlay Brothers’), ended in his suicide in<br />

1985, inspiring another song, ‘Jump They Say’. “I<br />

saw so little of him and I think I unconsciously<br />

exaggerated his importance for me,” David said in<br />

1993. “I invented this hero-worship to discharge my<br />

guilt and failure, and to set myself free from my own<br />

hang-ups.” In the card that accompanied his funeral<br />

bouquet, <strong>Bowie</strong> wrote “You’ve seen more things than<br />

we could imagine…”

Lindsay Kemp<br />

Ken Pitt introduced <strong>Bowie</strong> to bourgeois art forms. In<br />

1967-68, maverick dancer Lindsay Kemp, who’d<br />

trained under mime master Marcel Marceau, invited<br />

<strong>Bowie</strong> into a more relaxed world that revolved<br />

around the Dance Centre in Covent Garden. There,<br />

<strong>Bowie</strong> learned about make-up, bodily control and<br />

flamboyant characters, the likes of whom he’d not<br />

come across in pop circles. “Wonderful, incredible,”<br />

said <strong>Bowie</strong> years later. “The whole thing was so<br />

excessively French, with Left Bank existentialism,<br />

reading Genet and listening to R&B. The perfect<br />

Bohemian life.”<br />

Anthony Newley<br />

One decidedly strange interlude during <strong>Bowie</strong>’s long<br />

march to discovering his ‘true’ voice was the<br />

appropriation of the mannered Mockney style of oldschool<br />

showbiz star Anthony Newley. His 1967 debut<br />

album might just as well have been titled <strong>Bowie</strong><br />

Sings Tony. “Yes, we have another Tony Newley<br />

here alright,” quipped a New Musical Express<br />

reviewer.

Jacques Brel<br />

<strong>Bowie</strong> discovered Belgian chanson singer Jacques<br />

Brel in 1967 via a tribute record put together by Mort<br />

Schuman. Brel’s ‘My Death’ was a regular fixture in<br />

<strong>Bowie</strong>’s set between 1969 and 1973, by which time<br />

it was fully integrated into the Ziggy schema. Another<br />

Brel song, ‘Port Of Amsterdam’, was released as a<br />

B-side in 1973; meanwhile, Ziggy’s famous “You’re<br />

not alone” denouement was also Brel-inspired.<br />

Scott Walker<br />

The errant Walker Brothers frontman, who broke up<br />

the band and embarked on a genuinely enigmatic<br />

solo career, proved to <strong>Bowie</strong> that taking musical<br />

risks didn’t necessarily mean following the latest<br />

underground fad. Walker covered Brel songs,<br />

littered his lyrics with cultured and cinematic<br />

references and, David admitted in 1993, dated one<br />

of <strong>Bowie</strong>’s early girlfriends. Black Tie White Noise<br />

includes a version of Scott’s ‘Nite Flights’, from an<br />

LP inspired by <strong>Bowie</strong>’s ‘Heroes’.<br />

Mick Jagger

<strong>Bowie</strong> has always had sneaking admiration for the<br />

Rolling Stones frontman, a master of disguises<br />

whose ability to move with the times provides the<br />

template for rock’n’roll longevity. Jagger’s white Mr.<br />

Fish frock, elegantly worn at the Stones’ Hyde Park<br />

show in 1969, pre-empted <strong>Bowie</strong>’s “man’s dress”.<br />

(David attended the open-air gig where he heard<br />

‘Space Oddity’ previewed over the PA). Mick’s<br />

brilliant, persona-skipping character in Performance<br />

(1968), anticipated the role-playing riddles of Ziggy<br />

et al.<br />

Jagger in Hyde Park, 1969. “David has a much deeper<br />

essence than Mick. <strong>Bowie</strong> is an absolute deflector of<br />

whatever’s fashionable.” - Performance director, Nicolas Roeg.<br />

Tony Visconti recalls Bolan’s brief (below) contribution to<br />

‘London Bye Ta Ta’: “Just before David sings, “I loved her, I

loved her,” there’s a very high, whining guitar - that’s Marc.”<br />

Ray Davies<br />

The influence of the Kinks’ frontman, especially his<br />

well-observed vignettes of London life, cannot be<br />

underestimated. <strong>Bowie</strong> ended Pin Ups with a<br />

poignant version of Davies’ ‘Where Have All The<br />

Good Times Gone’, and also acknowledged The<br />

Kinks’ ‘All Day And All Of The Night’ on a 1996 tour.<br />

Syd Barrett<br />

Beautiful, terrifyingly gifted and blessed with the<br />

bittersweet curse of tragedy, Pink Floyd’s original<br />

songwriter might have been dismissive about<br />

<strong>Bowie</strong>’s ‘Love You Till Tuesday’ single (“I don’t think<br />

my toes were tapping at all”) in a magazine review,<br />

but his sharp fall from grace no doubt provided<br />

valuable source material for Ziggy Stardust. Barrett’s<br />

lyrics drew on mysticism, space travel, social<br />

observation and an unhealthy dose of childish<br />

whimsy, mirrored those of the late Sixties <strong>Bowie</strong>.<br />

David covered Barrett’s 1967 Pink Floyd hit, “See<br />

Emily Play”, on Pin Ups in 1973.

Buddha<br />

<strong>Bowie</strong>’s interest in this Eastern philosophy has been<br />

dismissed as little more than a fad by Angie <strong>Bowie</strong><br />

and Ken Pitt, but references continue to find their<br />

way into his work. Buddhism’s most enduring legacy<br />

on <strong>Bowie</strong> may have impacted on a subconscious<br />

level. Reincarnation, the exchange of one identity for<br />

another, is a Buddhist belief. By tearing his mortal<br />

self apart at regular intervals, it could be said that<br />

<strong>Bowie</strong> was merely accelerating the process.<br />

Marc Bolan<br />

<strong>Bowie</strong> wasn’t the only ex-Mod wannabe from an<br />

unfashionable corner of London to alter the course of<br />

British rock during the early Seventies.<br />

His companion and sometime rival was T. Rex

mainman Marc Bolan, whose revivalist rock’n’roll<br />

riffs, flamboyant, look-at-me costumes and<br />

extravagant persona, provided a template for David<br />

to meddle with. Between 1968 and 1970, they<br />

shared producer, Tony Visconti, but ‘officially’<br />

collaborated on record in just one day when Marc<br />

played guitar on <strong>Bowie</strong>’s ‘The Prettiest Star’ and<br />

‘London Bye Ta Ta’. After a period of intense rivalry,<br />

the pair were briefly reunited for an appearance on<br />

Bolan’s TV show in 1977, before Marc was killed in<br />

a car crash a week later. <strong>Bowie</strong> has occasionally<br />

performed Bolan’s work, duetting with Morrissey on<br />

‘Cosmic Dancer’ and in 1999 with Placebo for ‘20th<br />

Century Boy’.<br />

The Lower Third in Manchester Square, August 1965.<br />

Warwick Square, 1966. “I prefer to observe London from<br />

the outside, and to write about it.”

“There were some good tailors. The one I used to go to was<br />

the same one that Marc Bolan used to go to, a fairly well-known<br />

one in Shepherd’s Bush. I remember I saved up and got one suit<br />

made there.<br />

“I didn’t really have a hangout for clothes. I didn’t wear<br />

much that was fashionable, actually. I was quite happy with<br />

things like Fred Perrys and a pair of slacks.”<br />

bouffant just one step ahead of the adventurous<br />

pack, he became increasingly frustrated by failure.<br />

The Lower Third gave way to The Buzz in 1966, but<br />

with no appreciable change in fortunes, David<br />

sacked them before the year was out citing financial<br />

difficulties. The nearest he got to stardom was going<br />

to gigs in his manager’s Mark 10 Jaguar.<br />

But help was at hand. In September 1965, David’s<br />

then manager Ralph Horton was discussing his<br />

client with Ken Pitt, who’d been instrumental in the<br />

success of Manfred Mann a year or two earlier. Pitt<br />

advised him that with several David Jones’s already<br />

struggling to find a foothold in the business, including<br />

one young Mancunian soon to find fame with The<br />

Monkees, Horton’s charge ought to consider a name

change. He’d briefly called himself Dave Jay during<br />

The Kon-rads days, but for this do-or-die change, he<br />

instead delved back to his schoolboy fascination for<br />

the Wild West and came up with a name derived<br />

from a popular hunting knife used by Jim <strong>Bowie</strong>, a<br />

hero at the battle of the Alamo. From now on, he<br />

would be known as David <strong>Bowie</strong>.<br />

Rehearsals for Ready Steady Go! with The Buzz, March<br />

1966. The jacket was part of a “beautiful suit that I had made at<br />

Burtons. A tweed job, double-breasted with an Edwardian feel to<br />

it,” <strong>Bowie</strong> recalls.

With the male answer to the Dusty Springfield beehive up<br />

top, the artist formerly known as Jones looks to possible solo<br />

success. Some claim the change was also inspired by a<br />

mysterious uncle already blessed with the <strong>Bowie</strong> name.

MICK ROCK<br />

<strong>Bowie</strong>, pictured with photographer Mick Rock, in July 1973:<br />

“David has developed a true sense of his own mystique. He<br />

makes a fascinating study.”<br />

Mick Rock’s photographs chronicled the crucial<br />

months during 1972 and ‘73, when Ziggy Stardust<br />

and Aladdin Sane exploded onto the world stage.<br />

He was the only cameraman allowed inside the<br />

<strong>Bowie</strong> camp on a regular basis during this era.<br />

“The visual thing is what established him, the<br />

outrageousness of the costumes. My famous picture<br />

of him biting Mick Ronson’s guitar, which they ran as<br />

a full page ad in Melody Maker, got seen all over the<br />

place so that helped a lot. When I first met David, in<br />

February 1972 during the early stages of Ziggy<br />

Stardust, his image was very different from what it<br />

became at the end when it was super-sophisticated.<br />

He’d just got the hairdo done. It was more blond<br />

then, more his own colour, but it wasn’t long before it<br />

became the red that we know and love.

“He loves novelty, and will incorporate any new clothes or<br />

movements or attitudes into the detail of his repetoire on or off<br />

stage.”<br />

“Clearly he caught the zeitgeist in some interesting<br />

way. David is super bright but he’s also extremely<br />

intuitive about people and ideas. By the summer,<br />

after Ziggy had taken off, he was already producing<br />

Lou Reed and Mott The Hoople and he was hustling<br />

Iggy around. He became influential very quickly, not<br />

just in rock’n’roll terms but in the wider culture. I don’t<br />

think you could say he planned it all; he was like a<br />

force of nature. David is a very positive thinker, and<br />

always has been, even in his darkest hours.<br />

“Something happened to him around the time I met<br />

him and it galvanised everyone around him, me<br />

included. I art directed the Pin Ups album and put<br />

together the promo films for ‘John, I’m Only Dancing’,<br />

‘Life On Mars?’, ‘Space Oddity’ and ‘The Jean<br />

Genie’. I was a bit of a Josef Goebbels at the time!<br />

David had a very empathetic way that made him<br />

inspire others. I mean, people still talk about<br />

Transformer and Raw Power and All The Young<br />

Dudes as being the most significant albums in the<br />

careers of those three acts. David was the<br />

centrifugal force that drove this magic moment in<br />

time.

“It was all done on a shoestring with smoke and<br />

mirrors. They rarely spent much money on it, not in<br />

the early days. The illusion was of this massive star,<br />

looking and acting like a star, and suddenly he<br />

became that. Marc Bolan was cute and big and got<br />

there first, but he didn’t have the range and power<br />

that David had, or his intellect. David had great<br />

music and great visual appeal; he was ridiculously<br />

glamorous. Eventually, I think it started to exceed his<br />

wildest dreams. He sang about being a star before<br />

he was one; that’s all over the Ziggy Stardust album.<br />

Before that, no one was interested, especially in<br />

England. That’s why the Hunky Dory deal was done<br />

in America.<br />

“The photo sessions were all very different. I got<br />

some great performance shots because he always<br />

looked so fantastic. I actually wasn’t very good at live<br />

pictures because I’d not done much of that before<br />

David, but it was through him that I got good. There<br />

was so much stylised behaviour in his performance<br />

that he was great to shoot. It was like watching a<br />

kaleidoscope; he just kept changing on stage.<br />

“Taking the pictures happened very fast. There<br />

was very little planning; it was all action, all about<br />

interchange and interplay, a fast-paced intuitive<br />

thing. The control of the look was not contrived. It<br />

simply amounted to not letting photographers in so<br />

that they wanted to come in even more! I think he<br />

was the first to play that one, and I became part of<br />

the game. I was the exclusive photographer because<br />

no one else was really interested at the time. Then all<br />

that changed and it became, ‘Only Mick Rock can<br />

shoot him’. And that worked very well.<br />

“I had no warning for that fellatio shot, which I took<br />

at Oxford Town Hall in June 1972 (right). I was at the<br />

front of the stage, and when I moved to side, David<br />

suddenly did it. I remember him coming off stage<br />

and saying, ‘Did you get it, did you get it?’ I didn’t<br />

know if it was planned or spontaneous, but he was<br />

always looking for a move that would break through.<br />

That one really did!<br />

“I developed the shots the next morning, and took<br />

them round to the GEM office. David and Tony

picked out the shot they liked best and rushed it off<br />

to the printers. They both knew it was a master<br />

image. They bought a page in Melody Maker and<br />

ran it like a fan advert. Looking back, it’s a bit like<br />

Jimi Hendrix lighting his guitar or Pete Townshend<br />

smashing his up. David might regard that photo as<br />

being one of the key images of his career. It certainly<br />

made a dramatic and controversial statement.<br />

“<strong>Bowie</strong> is the first pop musician to wed the sensibility of<br />

film with that of rock ‘n’ roll image manipulation, the selfconscious<br />

presentation of self, is so much part of his nature.”<br />

“Androgyny was in the air and David was<br />

undoubtedly the finest manifestation of that. It was an<br />

innate part of his personality. If truth be told, David is<br />

very much a boy – I know a lot of girls he had sex<br />

with! But he would play up like English schoolboys<br />

do, groping and romping in the playground. You<br />

don’t get that in America; it’s very English. He<br />

developed that, and it became part of him.<br />

“He loved the camera when that wasn’t the ethic of<br />

the time. David would give you what you wanted, he<br />

was always up for it. I was able to work off that, but I<br />

wasn’t allowed to photo Marc Bolan ‘cos he and<br />

David weren’t talking at the time. Marc wanted me to<br />

do stuff for him and wanted to stick his finger up to<br />

David! When they were younger, they were close for<br />

a long time, then something went wrong. When<br />

David got big, he then felt generous towards Marc.<br />

“He’s always up to something, even today. He<br />

never sits still; he’s got an enormous amount of<br />

energy. He’s still in control of his image, but also now<br />

his destiny. He used to be very passive about the<br />

business side, but now he gets very involved. Once

he’d sign anything without reading it, but he’s learnt<br />

from his mistakes.”

Going Down I, with Mick Ronson, a seminal moment in rock<br />

history. “I’m very into shock tactics. I want to stretch people and<br />

get a reaction. I don’t think there’s any point in doing anything<br />

artistically unless it astounds,” <strong>Bowie</strong> announced.

1.3<br />

Renaissancemanbowie<br />

In paisley. “Aah, this is sweet. It was taken in around ‘67. I<br />

was 20. I look very young, very fresh -faced. There’s a bit of a<br />

psychedelic shirt going on as well.”

In 1967, <strong>Bowie</strong> put the youthful experiments with<br />

jazz, R&B and the Mod scene behind him. He placed<br />

himself under the tutelage of manager Ken Pitt,<br />

broadened his artistic horizons paying scant<br />

attention to contemporary trends and began to forge<br />

a new individualism. Their relationship, lovingly<br />

chronicled in Pitt’s book, The Pitt Report, was, in the<br />

singer’s estimation, “Pygmalion-like, to a certain<br />

extent”. <strong>Bowie</strong> came to Pitt a battle-scarred young<br />

man, knocked back by three years of professional<br />

failure. He left a pop star, secure enough in his own<br />

abilities that he could step out of the limelight until<br />

the conditions for a more enduring success looked<br />

more favourable. It was, he said later, his<br />

“apprenticeship period”.<br />

Posterity has not always been kind to Pitt’s role.<br />

Many feel he was out of his depth in the rapidly<br />

changing market, where muscular managers like<br />

Peter Grant (Led Zeppelin) and Allen Klein (The<br />

Beatles, The Rolling Stones) kept their noses out of<br />

their clients’ creative affairs, concentrating instead<br />

on the aggressive pursuit of money, security and<br />

more money. <strong>Bowie</strong>’s ex-wife Angie dismisses Pitt’s<br />

desire to mould <strong>Bowie</strong> into a “Judy Garland for the<br />

rock generation”, forgetting that during the early<br />

Seventies <strong>Bowie</strong> became almost exactly that. Under<br />

Pitt, <strong>Bowie</strong> affected an exaggerated Cockney voice<br />

as if he aspired to become the Tommy Steele or<br />

Anthony Newley of the Love Generation. Perhaps so,<br />

but Pitt’s encouragement and dedication to the idea<br />

of creating an intellectually adept, multi-skilled pop<br />

star provided the basis for <strong>Bowie</strong>’s future success.<br />

<strong>Bowie</strong>’s thirst for intellectual nourishment wasn’t<br />

wholly created by Pitt, though. His aspirations<br />

beyond fashion and pop fame were evident as early<br />

as February 1966 when Melody Maker printed ‘A<br />

Message To London From Dave’: “I want to act. I’d<br />

like to do character parts. I think it takes a lot to<br />

become somebody else; it takes some doing… As<br />

far as I’m concerned, the whole idea of Western life<br />

– that’s the life we live now – is wrong. These are

hard concepts to put into song, though.” A<br />

contemporary press release echoes the change in<br />

visual terms: “Gone are the outlandish clothes, the<br />

long hair, and the wild appearance and instead we<br />

find a quiet talented vocalist and songwriter in David<br />

<strong>Bowie</strong>.”<br />

When Pitt first clasped eyes on <strong>Bowie</strong>, after a<br />

Marquee Club performance in April 1966, the effect<br />

was immediate: “His burgeoning charisma was<br />

undeniable but I was particularly struck by the artistry<br />

with which he used his body, as if it were an<br />

accompanying instrument, essential to the singer<br />

and the song.” He also recognised <strong>Bowie</strong>’s innate<br />

intellect and wanted to nurture it.

In June 1967, as his debut LP was issued, <strong>Bowie</strong><br />

announced, “I’d like to write a musical. And really the ultimate<br />

would be to have one or two of my songs become standards,<br />

and used by artistes like Frank Sinatra.”

GAY GAMES<br />

This European CD of Sixties recordings, with an alternative<br />

slate grey dress shot from The Man Who Sold The World photo<br />

sessions, appeared in 1995.<br />

In April 1971, the Daily Mirror ran a piece on the<br />

cover of <strong>Bowie</strong>’s latest album, The Man Who Sold<br />

The World. The singer was pictured in repose on a<br />

chaise longue that had been draped in blue velvet.<br />