December 2012 - Journal of Threatened Taxa

December 2012 - Journal of Threatened Taxa

December 2012 - Journal of Threatened Taxa

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

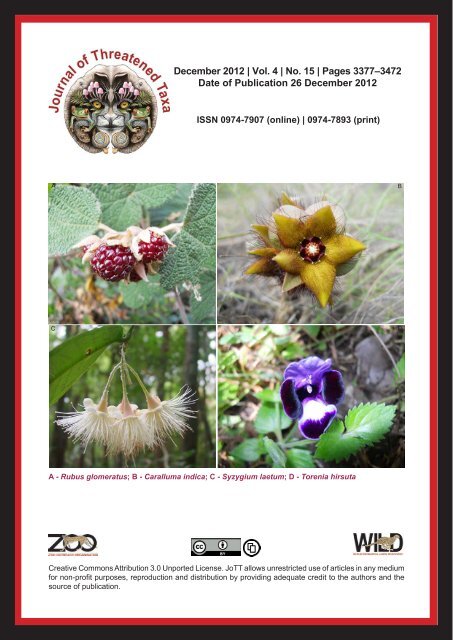

<strong>December</strong> <strong>2012</strong> | Vol. 4 | No. 15 | Pages 3377–3472<br />

Date <strong>of</strong> Publication 26 <strong>December</strong> <strong>2012</strong><br />

ISSN 0974-7907 (online) | 0974-7893 (print)<br />

A<br />

B<br />

C<br />

D<br />

A - Rubus glomeratus; B - Caralluma indica; C - Syzygium laetum; D - Torenia hirsuta<br />

Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. JoTT allows unrestricted use <strong>of</strong> articles in any medium<br />

for non-pr<strong>of</strong>it purposes, reproduction and distribution by providing adequate credit to the authors and the<br />

source <strong>of</strong> publication.

Jo u r n a l o f Th r e a t e n e d Ta x a<br />

Published by<br />

Wildlife Information Liaison Development Society<br />

Typeset and printed at<br />

Zoo Outreach Organisation<br />

96, Kumudham Nagar, Vilankurichi Road, Coimbatore 641035, Tamil Nadu, India<br />

Ph: +91422 2665298, 2665101, 2665450; Fax: +91422 2665472<br />

Email: threatenedtaxa@gmail.com, articlesubmission@threatenedtaxa.org<br />

Website: www.threatenedtaxa.org<br />

EDITORS<br />

Fo u n d e r & Ch i e f Ed i t o r<br />

Dr. Sanjay Molur, Coimbatore, India<br />

Ma n a g in g Ed i t o r<br />

Mr. B. Ravichandran, Coimbatore, India<br />

As s o c ia t e Ed i t o r s<br />

Dr. B.A. Daniel, Coimbatore, India<br />

Dr. Manju Siliwal, Dehra Dun, India<br />

Dr. Meena Venkataraman, Mumbai, India<br />

Ms. Priyanka Iyer, Coimbatore, India<br />

Ed i t o r ia l Ad v i s o r s<br />

Ms. Sally Walker, Coimbatore, India<br />

Dr. Robert C. Lacy, Minnesota, USA<br />

Dr. Russel Mittermeier, Virginia, USA<br />

Dr. Thomas Husband, Rhode Island, USA<br />

Dr. Jacob V. Cheeran, Thrissur, India<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>. Dr. Mewa Singh, Mysuru, India<br />

Dr. Ulrich Streicher, Oudomsouk, Laos<br />

Mr. Stephen D. Nash, Stony Brook, USA<br />

Dr. Fred Pluthero, Toronto, Canada<br />

Dr. Martin Fisher, Cambridge, UK<br />

Dr. Ulf Gärdenfors, Uppsala, Sweden<br />

Dr. John Fellowes, Hong Kong<br />

Dr. Philip S. Miller, Minnesota, USA<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>. Dr. Mirco Solé, Brazil<br />

Ed i t o r ia l Bo a r d / Su b j e c t Ed i t o r s<br />

Dr. M. Zornitza Aguilar, Ecuador<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>. Wasim Ahmad, Aligarh, India<br />

Dr. Sanit Aksornkoae, Bangkok, Thailand.<br />

Dr. Giovanni Amori, Rome, Italy<br />

Dr. István Andrássy, Budapest, Hungary<br />

Dr. Deepak Apte, Mumbai, India<br />

Dr. M. Arunachalam, Alwarkurichi, India<br />

Dr. Aziz Aslan, Antalya, Turkey<br />

Dr. A.K. Asthana, Lucknow, India<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>. R.K. Avasthi, Rohtak, India<br />

Dr. N.P. Balakrishnan, Coimbatore, India<br />

Dr. Hari Balasubramanian, Arlington, USA<br />

Dr. Maan Barua, Oxford OX , UK<br />

Dr. Aaron M. Bauer, Villanova, USA<br />

Dr. Gopalakrishna K. Bhat, Udupi, India<br />

Dr. S. Bhupathy, Coimbatore, India<br />

Dr. Anwar L. Bilgrami, New Jersey, USA<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>. Dr. Wolfgang Böhme, Adenauerallee, Germany<br />

Dr. Renee M. Borges, Bengaluru, India<br />

Dr. Gill Braulik, Fife, UK<br />

Dr. Prem B. Budha, Kathmandu, Nepal<br />

Mr. Ashok Captain, Pune, India<br />

Dr. Cle<strong>of</strong>as R. Cervancia, Laguna , Philippines<br />

Dr. Apurba Chakraborty, Guwahati, India<br />

Mrs. Norma G. Chapman, Suffolk, UK<br />

Dr. Kailash Chandra, Jabalpur, India<br />

Dr. Anwaruddin Choudhury, Guwahati, India<br />

Dr. Richard Thomas Corlett, Singapore<br />

Dr. Gabor Csorba, Budapest, Hungary<br />

Dr. Paula E. Cushing, Denver, USA<br />

Dr. Neelesh Naresh Dahanukar, Pune, India<br />

Dr. A.K. Das, Kolkata, India<br />

Dr. Indraneil Das, Sarawak, Malaysia<br />

Dr. Rema Devi, Chennai, India<br />

Dr. Nishith Dharaiya, Patan, India<br />

Dr. Ansie Dippenaar-Schoeman, Queenswood, South<br />

Africa<br />

Dr. William Dundon, Legnaro, Italy<br />

Dr. Gregory D. Edgecombe, London, UK<br />

Dr. J.L. Ellis, Bengaluru, India<br />

Dr. Susie Ellis, Florida, USA<br />

Dr. Zdenek Faltynek Fric, Czech Republic<br />

Dr. Carl Ferraris, NE Couch St., Portland<br />

Dr. R. Ganesan, Bengaluru, India<br />

Dr. Hemant Ghate, Pune, India<br />

Dr. Dipankar Ghose, New Delhi, India<br />

Dr. Gary A.P. Gibson, Ontario, USA<br />

Dr. M. Gobi, Madurai, India<br />

Dr. Stephan Gollasch, Hamburg, Germany<br />

Dr. Michael J.B. Green, Norwich, UK<br />

Dr. K. Gunathilagaraj, Coimbatore, India<br />

Dr. K.V. Gururaja, Bengaluru, India<br />

Dr. Mark S. Harvey,Welshpool, Australia<br />

Dr. Magdi S. A. El Hawagry, Giza, Egypt<br />

Dr. Mohammad Hayat, Aligarh, India<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>. Harold F. Heatwole, Raleigh, USA<br />

Dr. V.B. Hosagoudar, Thiruvananthapuram, India<br />

Dr. B.B.Hosetti, Shimoga, India<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>. Fritz Huchermeyer, Onderstepoort, South Africa<br />

Dr. V. Irudayaraj, Tirunelveli, India<br />

Dr. Rajah Jayapal, Bengaluru, India<br />

Dr. Weihong Ji, Auckland, New Zealand<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>. R. Jindal, Chandigarh, India<br />

Dr. A.J.T. Johnsingh, India<br />

Dr. Pierre Jolivet, Bd Soult, France<br />

Dr. Rajiv S. Kalsi, Haryana, India<br />

Dr. Rahul Kaul, Noida,India<br />

Dr. Werner Kaumanns, Eschenweg, Germany<br />

Dr. Paul Pearce-Kelly, Regent’s Park, UK<br />

Dr. P.B. Khare, Lucknow, India<br />

Dr. Vinod Khanna, Dehra Dun, India<br />

Dr. Cecilia Kierulff, São Paulo, Brazil<br />

Dr. Shumpei Kitamura, Ishikawa, Japan<br />

Dr. Ignacy Kitowski, Lublin, Poland<br />

continued on the back inside cover

JoTT Co m m u n ic a t i o n 4(15): 3377–3389<br />

Pollination biology <strong>of</strong> the crypto-viviparous Avicennia<br />

species (Avicenniaceae)<br />

A.J. Solomon Raju 1 , P.V. Subba Rao 2 , Rajendra Kumar 3 & S. Rama Mohan 4<br />

1,4<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Environmental Sciences, Andhra University, Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh 530003, India<br />

2,3<br />

Ministry <strong>of</strong> Environment and Forests, Paryavaran Bhavan, CGO Complex, Lodhi Road, New Delhi 110003, India<br />

Email: 1 solomonraju@gmail.com (corresponding author), 2 pvsrao8@gmail.com, 3 rajekr.72@gmail.com<br />

Date <strong>of</strong> publication (online): 26 <strong>December</strong> <strong>2012</strong><br />

Date <strong>of</strong> publication (print): 26 <strong>December</strong> <strong>2012</strong><br />

ISSN 0974-7907 (online) | 0974-7893 (print)<br />

Editor: Cle<strong>of</strong>as Cervancia<br />

Manuscript details:<br />

Ms # o2919<br />

Received 20 August 2011<br />

Final received 06 <strong>December</strong> <strong>2012</strong><br />

Finally accepted 06 <strong>December</strong> <strong>2012</strong><br />

Citation: Raju, A.J.S., P.V.S. Rao, R. Kumar<br />

& S.R. Mohan (<strong>2012</strong>). Pollination biology<br />

<strong>of</strong> the crypto-viviparous Avicennia species<br />

(Avicenniaceae). <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Threatened</strong> <strong>Taxa</strong><br />

4(15): 3377–3389.<br />

Copyright: © A.J. Solomon Raju, P.V. Subba<br />

Rao, Rajendra Kumar & S. Rama Mohan <strong>2012</strong>.<br />

Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported<br />

License. JoTT allows unrestricted use <strong>of</strong> this<br />

article in any medium for non-pr<strong>of</strong>it purposes,<br />

reproduction and distribution by providing<br />

adequate credit to the authors and the source<br />

<strong>of</strong> publication.<br />

Author Details: See end <strong>of</strong> this article.<br />

Author Contribution: The field work was done<br />

by all but it is mainly carried out by AJSR and<br />

SRM. All four authors have contributed in the<br />

preparation <strong>of</strong> manuscript but Pr<strong>of</strong>. Raju is the<br />

main person among all.<br />

OPEN ACCESS | FREE DOWNLOAD<br />

Abstract: Floral biology, sexual system, breeding system, pollinators, fruiting and<br />

propagule dispersal ecology <strong>of</strong> crypto-viviparous Avicennia alba Bl., A. marina (Forsk.)<br />

Vierh. and A. <strong>of</strong>ficinalis L. (Avicenniaceae) were studied in Godavari mangrove forests<br />

<strong>of</strong> Andhra Pradesh State, India. All the three plant species initiate flowering following<br />

the first monsoon showers in June and cease flowering in late August. The flowers are<br />

hermaphroditic, nectariferous, protandrous, self-compatible and exhibit mixed breeding<br />

system. Self-pollination occurs even without pollen vector but fruit set in this mode<br />

is negligible. In all, the flowers are strictly entomophilous and the seedlings disperse<br />

through self-planting and stranding strategies.<br />

Keywords: Avicennia species, entomophily, mixed breeding system protandry, selfcompatibility.<br />

Introduction<br />

The family Avicenniaceae comprises <strong>of</strong> only one genus Avicennia.<br />

The genus consists <strong>of</strong> at least eight tree species which grow in the intertidal<br />

zone <strong>of</strong> coastal mangrove forests and ranges widely throughout<br />

tropical and warm temperate regions <strong>of</strong> the world (Tomlinson 1986; Duke<br />

1991). These species occupy diverse mangrove habitats, either within<br />

the normal tidal range or in back mangal and a high tolerance <strong>of</strong> hypersaline<br />

conditions. Of these, three species occur in Atlantic-East Pacific<br />

and five species in the Indo-West Pacific (Duke 1992). The East Africa<br />

and the Indo-Pacific species include A. <strong>of</strong>ficinalis, A. marina, A. alba, A.<br />

lanata, A. eucalyptifolia, A. balanophora and only the first three species<br />

reached the Indian subcontinent (Duke et al. 1998). A. <strong>of</strong>ficinalis has<br />

a wide range from southern India through Indo-Malaya to New Guinea<br />

and eastern Australia. A. marina has the broadest distribution, both<br />

latitudinally and longitudinally with a range from East Africa and the Red<br />

Sea along tropical and subtropical coasts <strong>of</strong> the Indian Ocean to the South<br />

China Sea, throughout much <strong>of</strong> Australia into Polynesia as far as Fiji, and<br />

south to the North Island <strong>of</strong> New Zealand (Tomlinson 1986). A. marina<br />

has the distinction <strong>of</strong> being the most widely distributed <strong>of</strong> all mangrove<br />

tree species. The ubiquitous presence in mangrove habitats around the<br />

world is due to the ability to grow and reproduce across a broad range<br />

<strong>of</strong> climatic, saline, and tidal conditions and to produce large numbers<br />

<strong>of</strong> buoyant propagules annually (Duke et al. 1998). A. alba has a wide<br />

distribution from India to Indochina, through the Malay Archipelago to<br />

the Philippines, New Guinea, New Britain, and northern Australia.<br />

Tomlinson (1986) gave a brief account <strong>of</strong> the floral biology <strong>of</strong><br />

Avicennia species. A. <strong>of</strong>ficinalis is self-compatible and occasionally self-<br />

<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Threatened</strong> <strong>Taxa</strong> | www.threatenedtaxa.org | <strong>December</strong> <strong>2012</strong> | 4(15): 3377–3389 3377

Pollination biology <strong>of</strong> Avicennia<br />

pollinating. Self-pollination <strong>of</strong> individuals is unlikely<br />

due to protandry, but the sequence and synchrony <strong>of</strong><br />

flowering, together with pollinator behaviour favours<br />

geitonogamy. Clarke & Meyerscough (1991) reported<br />

that it is pollinated by a variety <strong>of</strong> insects in Australia.<br />

These authors also reported that A. marina is visited<br />

by ants, wasps, bugs, flies, bee-flies, cantherid beetles,<br />

and moths but the most common visitor is Apis<br />

mellifera. Tomlinson (1986) described that A. alba,<br />

A. marina and A. <strong>of</strong>ficinalis have very similar flowers<br />

and hence may well be served by the same class, if<br />

not the same species <strong>of</strong> pollinators; when these species<br />

grow together, there is evidence <strong>of</strong> non-synchrony in<br />

flowering times, which might minimize the competition<br />

for pollinators (probably bees) and at the same time<br />

spread the availability <strong>of</strong> nectar over a more extended<br />

period. This state <strong>of</strong> information in a preliminary<br />

mode provided the basis for taking up the present<br />

study on the pollination biology <strong>of</strong> crypto-viviparous<br />

Avicennia alba Bl., A. marina (Forsk.) Vierh. and A.<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficinalis L. in Coringa mangrove forest <strong>of</strong> Andhra<br />

Pradesh. This paper describes the details <strong>of</strong> floral<br />

biology, sexual system, breeding system, pollinators<br />

and seedling ecology <strong>of</strong> these three Avicennia species.<br />

Further, these aspects have been discussed in the light<br />

<strong>of</strong> the existing relevant literature.<br />

Materials and Methods<br />

Floral biology<br />

The crypto-viviparous Avicennia alba, A. marina<br />

and A. <strong>of</strong>ficinalis (Avicenniaceae) occurring in<br />

Godavari mangrove forest (16 0 30’–17 0 00’N & 82 0 10’–<br />

80 0 23’E) in the state <strong>of</strong> Andhra Pradesh, India, were<br />

used for the present study. The study was conducted<br />

during February 2008–April 2010. Regular field trips<br />

were conducted to track the flowering season in order<br />

to take up intensive field studies at weekly intervals<br />

during their flowering and fruiting season. The flower’s<br />

morphological characteristics were described based<br />

on 25 flowers collected at random for each species.<br />

Quantification <strong>of</strong> the number <strong>of</strong> flowers produced per<br />

inflorescence and the duration <strong>of</strong> inflorescence were<br />

determined by tagging 10 inflorescences, which have<br />

not initiated flowering, selected at random and following<br />

them daily until they ceased flowering permanently.<br />

Anthesis was initially recorded by observing marked<br />

A.J.S. Raju et al.<br />

mature buds in the field. Later, the observations<br />

were repeated 3–4 times on different days during<br />

0600–1400 hr in order to provide accurate anthesis<br />

schedule for each plant species. Similarly, the mature<br />

buds were followed for recording the time <strong>of</strong> anther<br />

dehiscence. The presentation pattern <strong>of</strong> pollen was<br />

also investigated by recording how anthers dehisced<br />

and confirmed by observing the anthers under a 10x<br />

hand lens. Twenty five mature but undehisced anthers<br />

was collected from different plants and placed in a petri<br />

dish. Later, each time a single anther was taken out<br />

and placed on a clean microscope slide (75x25 mm)<br />

and dabbed with a needle in a drop <strong>of</strong> lactophenolaniline-blue.<br />

The anther tissue was then observed<br />

under the microscope for pollen, if any, and if pollen<br />

grains were not there, the tissue was removed from the<br />

slide. The pollen mass was drawn into a band, and<br />

the total number <strong>of</strong> pollen grains was counted under a<br />

compound microscope (40x objective, 10x eye piece).<br />

This procedure was followed for counting the number<br />

<strong>of</strong> pollen grains in each anther collected. Based on<br />

these counts, the mean number <strong>of</strong> pollen produced per<br />

anther was determined. The mean pollen output per<br />

anther was multiplied by the number <strong>of</strong> anthers in the<br />

flower for obtaining the mean number <strong>of</strong> pollen grains<br />

per flower. The characteristics <strong>of</strong> pollen grains were<br />

also recorded. The pollen-ovule ratio was determined<br />

by dividing the average number <strong>of</strong> pollen grains per<br />

flower by the number <strong>of</strong> ovules per flower. The value<br />

thus obtained was taken as pollen-ovule ratio (Cruden<br />

1977). The presence <strong>of</strong> nectar was determined by<br />

observing the mature buds and open flowers. The<br />

volume <strong>of</strong> nectar from 20 flowers collected at random<br />

from each plant species was determined. Then, the<br />

average volume <strong>of</strong> nectar per flower was determined<br />

and expressed in µl. The flowers used for this purpose<br />

were bagged at mature bud stage, opened after anthesis<br />

and squeezed nectar into micropipette for measuring<br />

the volume <strong>of</strong> nectar. Nectar sugar concentration<br />

was determined using a Hand Sugar Refractometer<br />

(Erma, Japan). For the analysis <strong>of</strong> sugar types, paper<br />

chromatography method described by Harborne (1973)<br />

was followed. Nectar was placed on Whatman No. 1<br />

<strong>of</strong> filter paper along with standard samples <strong>of</strong> glucose,<br />

fructose and sucrose. The paper was run ascendingly<br />

for 24 hours with a solvent system <strong>of</strong> n-butanolacetone-water<br />

(4:5:1), sprayed with aniline oxalate<br />

spray reagent and dried at 120 0 C in an electric oven<br />

3378<br />

<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Threatened</strong> <strong>Taxa</strong> | www.threatenedtaxa.org | <strong>December</strong> <strong>2012</strong> | 4(15): 3377–3389

Pollination biology <strong>of</strong> Avicennia<br />

for 20 minutes for the development <strong>of</strong> spots from the<br />

nectar and the standard sugars. Then, the sugar types<br />

present and also the most dominant sugar type were<br />

recorded based on the area and colour intensity <strong>of</strong> the<br />

spot. Nectar amino acid types present in A. <strong>of</strong>ficinalis<br />

were also recorded as per the paper chromatography<br />

method <strong>of</strong> Baker & Baker (1973). Nectar was spotted<br />

on Whatman No. 1 filter paper along with the standard<br />

samples <strong>of</strong> 19 amino acids, namely, alanine, arginine,<br />

aspartic acid, cysteine, cystine, glutamic acid, glycine,<br />

histidine, isolecuine, leucine, lysine, methionine,<br />

phenylalanine, proline, serine, threonine, tryptophan,<br />

tyrosine and valine. The paper was run ascendingly<br />

in chromatography chamber for 24 hours with a<br />

solvent system <strong>of</strong> n-butanol-glacial acetic acid-water<br />

(4:1:5). The chromatogram was detected with 0.2%<br />

ninhydrin reagent and dried at 85 0 C in an electric oven<br />

for 15 minutes for the development <strong>of</strong> spots from the<br />

nectar and the standard amino acids. The developed<br />

nectar spots were compared with the spots <strong>of</strong> the<br />

standard amino acids. Then, the amino acid types<br />

were recorded. The stigma receptivity was observed<br />

visually and by H 2<br />

O 2<br />

test. In visual method, the stigma<br />

physical state (wet or dry) and the unfolding <strong>of</strong> its<br />

lobes were considered to record the commencement<br />

<strong>of</strong> receptivity; withering <strong>of</strong> the lobes was taken as loss<br />

<strong>of</strong> receptivity. H 2<br />

O 2<br />

test as given in Dafni et al. (2005)<br />

was followed for noting stigma receptivity period.<br />

Pollinators<br />

The insect species visiting the flowers were<br />

observed visually and by using Olympus Binoculars<br />

(PX35 DPSR Model). There was no night time<br />

foraging activity at the flowers. Their foraging activity<br />

was confined to daytime only and were observed on a<br />

number <strong>of</strong> occasions on each plant species for their<br />

foraging behaviour such as mode <strong>of</strong> approach, landing,<br />

probing behaviour, the type <strong>of</strong> forage they collect,<br />

contact with essential organs to result in pollination<br />

and inter-plant foraging activity in terms <strong>of</strong> crosspollination.<br />

The foraging insects were captured during<br />

1000–1200 hr on each plant species and brought them<br />

to the laboratory. For each insect species, 10 specimens<br />

were captured and each specimen was washed first in<br />

ethyl alcohol, the contents stained with aniline-blue on<br />

a glass slide and observed under microscope to count<br />

the number <strong>of</strong> pollen grains present. In case <strong>of</strong> pollen<br />

collecting insects, pollen loads on their corbiculae<br />

A.J.S. Raju et al.<br />

were separated prior to washing them. From this, the<br />

average number <strong>of</strong> pollen grains carried by each insect<br />

species was calculated to know the pollen carryover<br />

efficiency <strong>of</strong> different insect species.<br />

Breeding system<br />

Mature flower buds <strong>of</strong> some inflorescences on<br />

different individuals were tagged and enclosed in butter<br />

paper bags for breeding experiments. The number<br />

<strong>of</strong> flower buds used for each mode <strong>of</strong> pollination for<br />

each species was given in Table 1. The stigmas <strong>of</strong><br />

flowers were pollinated with the pollen <strong>of</strong> the same<br />

flower manually by using a brush; they were bagged<br />

and followed to observe fruit set in manipulated<br />

autogamy. The flowers were fine-mesh bagged without<br />

hand pollination to observe fruit set in spontaneous<br />

autogamy. The emasculated flowers were handpollinated<br />

with the pollen <strong>of</strong> a different flower on the<br />

same plant; they were bagged and followed for fruit<br />

set in geitonogamy. The emasculated flowers were<br />

pollinated with the pollen <strong>of</strong> a different individual<br />

plant; they were bagged and followed for fruit set<br />

Table 1. Results <strong>of</strong> breeding experiments in Avicennia<br />

species<br />

Breeding system<br />

No. <strong>of</strong> flowers<br />

pollinated<br />

No. <strong>of</strong> flowers<br />

set fruit<br />

Fruit set<br />

(%)<br />

Avicennia alba<br />

Autogamy (bagged) 40 7 17.5<br />

Autogamy (handpollinated<br />

and bagged)<br />

20 8 40<br />

Geitonogamy 32 20 62.5<br />

Xenogamy 28 18 64.28<br />

Open pollinations 50 21 42<br />

Avicennia marina<br />

Autogamy (bagged) 25 3 12<br />

Autogamy (handpollinated<br />

and bagged)<br />

30 10 33.33<br />

Geitonogamy 25 10 40<br />

Xenogamy 25 17 68<br />

Open pollinations 45 25 55<br />

Avicennia <strong>of</strong>ficinalis<br />

Autogamy (bagged) 56 12 21.42<br />

Autogamy (handpollinated<br />

and bagged)<br />

35 15 42.85<br />

Geitonogamy 30 19 63.33<br />

Xenogamy 56 38 67.85<br />

Open pollinations 129 75 58.13<br />

<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Threatened</strong> <strong>Taxa</strong> | www.threatenedtaxa.org | <strong>December</strong> <strong>2012</strong> | 4(15): 3377–3389<br />

3379

Pollination biology <strong>of</strong> Avicennia<br />

in xenogamy. If fruit set is there, the percentage <strong>of</strong><br />

fruit set was calculated for each mode. The flowers/<br />

inflorescences were tagged on different plant species<br />

prior to anthesis and followed for fruit and seed set<br />

rate in open-pollinations.<br />

Seedling ecology<br />

Fruit maturation period and hypocotyl or seedling<br />

growth period prior to detachment from the parent tree<br />

were also recorded. Rose-ringed Parakeet feeding on<br />

fruit and/or hypocotyls <strong>of</strong> A. alba and A. marina was<br />

observed. A sample <strong>of</strong> fruits/hypocotyls was collected<br />

at random from these plant species to calculate the<br />

percentage <strong>of</strong> damage. Casual observations on<br />

seedling dispersal during low and high tide periods<br />

were made to record the dispersal mode.<br />

Photography<br />

Plant, flower and fruit details together with insect<br />

foraging activity on flowers were photographed with<br />

Nikon D40X Digital SLR (10.1 pixel) and TZ240<br />

Stereo Zoom Microscope with SP-350 Olympus<br />

Digital Camera (8.1 pixel).<br />

Results<br />

The three Avicennia species are evergreen trees with<br />

irregular spreading branches (Image 1a; 2a). Following<br />

monsoon showers in June, they initiate flowering and<br />

continue flowering until the end <strong>of</strong> August. Individual<br />

trees flower for 35±4 (Range 32–48) days in A. alba,<br />

33±2 (Range 32–35) days in A. marina and 38±4<br />

(Range 36–41) days in A. <strong>of</strong>ficinalis. In all the three<br />

species, the flowers are borne in terminal or axillary<br />

racemes/panicles (Image 1b; 2b; 2a). An inflorescence<br />

produces 52.34±26.96 flowers (Range 15–123) over a<br />

period <strong>of</strong> 25 days (Range 24–28) in A. alba, 47±13.97<br />

flowers (Range 26–76) over a period <strong>of</strong> 22 days (Range<br />

15–22) in A. marina and 32±11 flowers (Range 9–35)<br />

over a period <strong>of</strong> 16–25 days in A. <strong>of</strong>ficinalis.<br />

The flowers are sessile, small (4mm long; 3mm<br />

diameter), orange yellow, fragrant, actinomorphic and<br />

bisexual in all the three species. They are slightly<br />

scented in A. alba and A. marina while foetid in A.<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficinalis. The flowers are 4mm long and 3mm<br />

diameter in A. alba, 6mm long and 5mm diameter<br />

in A. marina, and 10mm long and 10mm diameter<br />

A.J.S. Raju et al.<br />

in A. <strong>of</strong>ficinalis. Calyx is short, elliptic and has four<br />

ovate, green, pubescent sepals with hairs on the outer<br />

surface. Corolla has four thick, orange yellow ovate<br />

petals forming a short tube at the base. The petals are<br />

glabrous inside and hairy outside in A. marina while<br />

the adaxial petal is the broadest and shallowly bi-lobed<br />

in A. <strong>of</strong>ficinalis. Stamens are four, epipetalous, occur<br />

at the throat <strong>of</strong> the corolla. The anthers are basifixed,<br />

exserted, introrse and arranged alternate to petals. The<br />

ovary is 2mm long in A. alba and A. marina while it is<br />

7mm long in A. <strong>of</strong>ficinalis. In all, it is conspicuously<br />

hairy and bicarpellary syncarpous with four imperfect<br />

locules and each locule contains one pendulous ovule.<br />

It is terminated with a 1–2 mm long glabrous style<br />

tapered to the bifid hairy stigma. The light yellow<br />

style and stigma arise from the center <strong>of</strong> the flower and<br />

stand erect throughout the flower life. In A. <strong>of</strong>ficinalis,<br />

the entire female structure is over-arched by stamens<br />

above. The style is bent, situated below the adaxial<br />

corolla lobe but not in the center <strong>of</strong> the flower.<br />

The mature buds open throughout the day but most<br />

buds opening during 0900–1200 hr in A. alba (Image<br />

1c,d), during 1000–1300 hr in A. marina (Image 2c,d)<br />

and during 0800–1100 hr in A. <strong>of</strong>ficinalis (Image<br />

3b–d). The petals slowly open and take 3–4 hours for<br />

complete opening to expose the stamens and stigma.<br />

The stamens bend inward overarching the stigma at<br />

anthesis and the all the anthers dehisce ½ hour after<br />

anthesis by longitudinal slits. The stigma is well<br />

seated in the center <strong>of</strong> the flower. In A. <strong>of</strong>ficinalis,<br />

the stamens gradually stand erect and bend backwards<br />

over a period <strong>of</strong> three days. After anthesis, the stigma<br />

grows gradually and becomes bifid on the morning<br />

<strong>of</strong> the 2 nd day in A. alba (Image 1e,f) and A. marina<br />

(Image 2e,f) and on the 3 rd day in A. <strong>of</strong>ficinalis (Image<br />

3e–h). The bifid condition <strong>of</strong> stigma is an indication<br />

<strong>of</strong> beginning <strong>of</strong> stigma receptivity and it remains<br />

receptive for two days in A. alba and A. marina, and for<br />

five days in A. <strong>of</strong>ficinalis. The stigmatic lobes recurve<br />

completely. The flower life is six days in A. alba, five<br />

days in A. marina and seven days in A. <strong>of</strong>ficinalis. The<br />

petals, stamens and stigma drop <strong>of</strong>f while the calyx is<br />

persistent in all the three species.<br />

The pollen production per anther is 1,967±31.824.3<br />

(Range 1,929–2,010) in A. alba, 1,643.2±31.8 (Range<br />

1,600–1,690) in A. marina and 2,444±202.4 (Range<br />

2,078–2,604) in A. <strong>of</strong>ficinalis. In all, the pollen grains<br />

are light yellow, granular, tricolporate, reticulate, muri<br />

3380<br />

<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Threatened</strong> <strong>Taxa</strong> | www.threatenedtaxa.org | <strong>December</strong> <strong>2012</strong> | 4(15): 3377–3389

Pollination biology <strong>of</strong> Avicennia<br />

A.J.S. Raju et al.<br />

Image 1. Avicennia alba. a - Habitat; b - Flower unit; c - Mature Bud; d - Flower; e - Stigma condition at anthesis; f - Bifid<br />

stigma on the 2 nd day; g–i - Flower visitors collecting nectar (g - Fly (unidentified); h - Everes lacturnus; i - Fruit set in<br />

open-pollinations)<br />

broad, flat, thick; lumina small irregularly shaped<br />

and colpi deeply intruding (Image 6a–c). Their size<br />

is 24.9μm in A. alba and 33.2μm in both A. marina<br />

and A. <strong>of</strong>ficinalis. The pollen-ovule ratio is 1,967:1<br />

in A. alba, 1,643.2:1 in A. marina and 2,209.3:1 in A.<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficinalis. In all, the flowers begin nectar secretion<br />

along with anther dehiscence. The nectar secretion<br />

occurs in minute amount which is accumulated at<br />

the ovary base and on the yellow part <strong>of</strong> petals; the<br />

nectar glitters against sunlight. A flower produces<br />

0.5±0.1 (Range 0.4–0.7) μl <strong>of</strong> nectar with 40% sugar<br />

concentration in A. alba, 0.4±0.08 (Range 0.3–0.5) μl<br />

<strong>of</strong> nectar with 38% sugar concentration in A. marina<br />

and 0.65±0.09 (Range 0.5–0.8) μl <strong>of</strong> nectar with 39%<br />

sugar concentration in A. <strong>of</strong>ficinalis. The sugar types<br />

included glucose and fructose and sucrose with the<br />

first as dominant in A. alba and A. marina and the last<br />

as dominant in A. <strong>of</strong>ficinalis in which the nectar amino<br />

acids included aspartic acid, cysteine, alanine, arginine,<br />

serine, cystine, proline, lysine, glycine, glutamic acid,<br />

threonine and histidine.<br />

In all three Avicennia species, the results <strong>of</strong><br />

breeding systems indicate that the flowers are selfcompatible<br />

and self-pollinating. In A. alba, the fruit<br />

set is 17.5% in spontaneous autogamy, 40% in handpollinated<br />

autogamy, 62.5% in geitonogamy, 64.28%<br />

in xenogamy and 42% in open pollination (Image<br />

1i) (Table 1). In A. marina, the fruit set is 12% in<br />

<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Threatened</strong> <strong>Taxa</strong> | www.threatenedtaxa.org | <strong>December</strong> <strong>2012</strong> | 4(15): 3377–3389<br />

3381

Pollination biology <strong>of</strong> Avicennia<br />

A.J.S. Raju et al.<br />

Image 2. Avicennia marina: a - Habitat; b - Flowering inflorescence; c - Mature bud; d - Flower; e - Stigma condition at<br />

anthesis; f - Bifid stigma on the 2nd day; g–j - Flower visitors collecting nectar (g - Unidentified fly; h - Eristalinus arvorum;<br />

i - Rhyncomya sp.; j - Fruit set in open-pollinations)<br />

spontaneous autogamy, 33.33% in hand-pollinated<br />

autogamy, 40% in geitonogamy, 68% in xenogamy<br />

and 55% in open pollination (Image 2j) (Table 1). In<br />

A. <strong>of</strong>ficinalis, the fruit set is 21.42% in spontaneous<br />

autogamy, 42.85% in hand-pollinated autogamy,<br />

63.33% in geitonogamy, 67.85% in xenogamy and<br />

58.13% in open pollination (Image 5a) (Table 1).<br />

The insects foraged the flowers <strong>of</strong> Avicennia<br />

species during day time from 0700–1700 hr. They<br />

were Apis dorsata, A. florea, Nomia sp., Chrysomya<br />

megacephala, an unidentified fly (Image 1g), Danaus<br />

chrysippus and Everes lacturnus (Image 1h) in A. alba;<br />

Halictus sp., Chrysomya megacephala, Eristalinus<br />

arvorum (Image 2h), Rhyncomya sp. (Image 2i),<br />

an unidentified fly (Image 2g), Polistis humilis and<br />

Catopsilia pyranthe in A. marina; and Apis dorsata<br />

(Image 4a), Xylocopa pubescens, Xylocopa sp. (Image<br />

4b,c), Eristalinus arvorum, Chrysomya megacephala<br />

(Image 4d), Sarcophaga sp. (Image 4e), Euploea core<br />

(Image 4j), Danaus chrysippus, D. genutia (Image 4h),<br />

3382<br />

<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Threatened</strong> <strong>Taxa</strong> | www.threatenedtaxa.org | <strong>December</strong> <strong>2012</strong> | 4(15): 3377–3389

Pollination biology <strong>of</strong> Avicennia<br />

A.J.S. Raju et al.<br />

Image 3. Avicennia <strong>of</strong>ficinalis. a - Flowering branch; b–d - Different stages <strong>of</strong> anthesis; e - Flower with bent unreceptive<br />

stigma with dehisced anthers; f - Flower with erect receptive stigma and withered anthers; g - Unreceptive stigma;<br />

h - Receptive stigma.<br />

Junonia lemonias, J. hierta (Image 4i), a fly (Image 4f)<br />

and a wasp (Image 4g) (unidentified) in A. <strong>of</strong>ficinalis.<br />

The flies visited the flowers in groups while all other<br />

insects visited individually. The bees were both pollen<br />

and nectar feeders while all other insects only nectar<br />

feeders. All the insects probed the flowers in upright<br />

position to collect the forage. In case <strong>of</strong> Xylocopa<br />

bees, they made audible buzzes while collecting<br />

nectar aliquots from the petals. Butterflies landed on<br />

the petals, stretched their proboscis to collect nectar<br />

aliquots on the petals and at the flower base. In this<br />

process, all the insects invariably touched the anthers<br />

and the stigma; the ventral side <strong>of</strong> all insects was found<br />

powdered with pollen. Further, the body washings <strong>of</strong><br />

the all insect species revealed the presence <strong>of</strong> pollen;<br />

the average number <strong>of</strong> pollen grains per insect for each<br />

species varied from 67.6 to 336.2; in A. alba from<br />

63.1 to 227.4, in A. marina, and from 73 to 550.2 in A.<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficinalis (Table 2). As the nectar is secreted in minute<br />

amounts, the insects made multiple visits to most <strong>of</strong><br />

the flowers on a tree and moved frequently between<br />

trees to collect nectar. Such foraging behaviour was<br />

considered to be effecting self- and cross-pollination.<br />

In all Avicennia species, pollinated and fertilized<br />

flowers initiate fruit development immediately and<br />

take about 4–6 weeks to produce mature fruits. In<br />

fertilized flowers, only one ovule produces seed.<br />

Fruit is a 1-seeded leathery pale green capsule with<br />

<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Threatened</strong> <strong>Taxa</strong> | www.threatenedtaxa.org | <strong>December</strong> <strong>2012</strong> | 4(15): 3377–3389<br />

3383

Pollination biology <strong>of</strong> Avicennia<br />

A.J.S. Raju et al.<br />

Image 4. Avicennia <strong>of</strong>ficinalis - Flower visitors. a - Apis dorsata; b & c - Xylocopa sp.; d - Chrysomya megacephala;<br />

e - Sarcophaga sp.; f - Unidentified fly collecting nectar; g - Wasp (unidentified); h - Danaus genutia; i - Junonia hierta;<br />

j - Euploea core.<br />

persistent reddish brown calyx. It is 40mm long,<br />

15mm wide in A. alba, 30–35 mm long, 25mm wide<br />

in A. marina and 30mm long, 25mm wide in A.<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficinalis. It is abruptly narrowed to a short beak<br />

and hairy throughout. Seed produces light green,<br />

hypocotyl which completely occupies the fruit cavity<br />

(Image 5b). Fruit set to the extent <strong>of</strong> 6% in A. alba<br />

and to the extent <strong>of</strong> 4% in A. marina was damaged<br />

by the Rose-ringed Parakeet Psittacula krameri which<br />

fed on the concealed hypocotyl in fruits and such fruits<br />

were found to be empty. In all three Avicennia species,<br />

the fruit together with hypocotyl falls <strong>of</strong>f the mother<br />

plant; settles in the substratum immediately at low<br />

tide period when the forest floor is exposed; it floats<br />

in water and disperses by tidal currents at high tide<br />

period until settled somewhere in the soil. The radicle<br />

side <strong>of</strong> hypocotyl penetrates the soil and produces root<br />

system while plumule side produces new leaves and<br />

subsequent aerial system. The fruit pericarp detaches<br />

and disintegrates when plumular leaves are produced.<br />

3384<br />

<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Threatened</strong> <strong>Taxa</strong> | www.threatenedtaxa.org | <strong>December</strong> <strong>2012</strong> | 4(15): 3377–3389

Pollination biology <strong>of</strong> Avicennia<br />

A.J.S. Raju et al.<br />

Table 2. Pollen pick up efficiency <strong>of</strong> foraging insects on<br />

Avicennia species<br />

Insect species<br />

Sample<br />

size<br />

Range<br />

Mean±S.D<br />

Avicennia alba<br />

Apis dorsata 10 219–476 336.2±88.7<br />

A. florea 10 129–327 227.5±64.1<br />

Nomia sp. 10 110–270 200.6±50.7<br />

Chrysomya megacephala 10 86–117 101.5±11.0<br />

Fly (unidentified) 10 56–98 67.6±8.5<br />

Danaus chrysippus 10 79–96 86.2±6.28<br />

Everes lacturnus 10 57–87 70.1±10.0<br />

Avicennia marina<br />

Halictus sp. 10 110–367 215.2±78.8<br />

Chrysomya megacephala 10 126–321 227.4±66.7<br />

Rhyncomya sp. 10 91–110 99.7±7.5<br />

Eristalinus arvorum 10 96–136 118.2±13.6<br />

Polistis humilis 10 56–73 63.1±6.0<br />

Catopsilia pyranthe 10 71–95 83.8±8.61<br />

Unidentified fly 10 66–106 84.4±14.4<br />

Avicennia <strong>of</strong>ficinalis<br />

Image 5. Avicennia <strong>of</strong>ficinalis<br />

a - Fruit set in open-pollinations; b - Propagule.<br />

a<br />

b<br />

Xylocopa pubescens 10 452–789 520.2±139.1<br />

Xylocopa sp. 10 412–681 550.2±125.2<br />

Apis dorsata 10 325–541 441.3±98.1<br />

a b c<br />

Image 6. Pollen grains <strong>of</strong> Avicennia species<br />

a - A. alba; b - A. marina; c - A. <strong>of</strong>ficinalis<br />

Eristalinus arvorum 10 142–251 190.5±51.3<br />

Chrysomya megacephala 10 98–131 112.5±25.1<br />

Sarcophaga sp. 10 105–120 110.5±23.1<br />

Euploea core 10 89–154 124.5±32.6<br />

Danaus chrysippus 10 56–110 73.0±29.2<br />

D. genutia 10 79–112 94.3±24.6<br />

Junonia lemonias 10 56–128 98.6±13.2<br />

J. hierta 10 91–120 102.5±21.1<br />

Unidentified fly 10 68–104 81.0±20.4<br />

Unidentified wasp 10 45–102 85.1±12.5<br />

Discussion<br />

All the three Avicennia species studied are<br />

principally polyhaline evergreen tree species. These<br />

tree species show flowering response to monsoon<br />

showers in June; the first monsoon showers seem to<br />

provide the necessary stimulus for flowering. Opler<br />

et al. (1976) and Ewusie (1980) have reported such a<br />

flowering response to light rains in summer season in<br />

a number <strong>of</strong> plants occurring in coastal environments.<br />

The flowering period extends until August in all the<br />

three species <strong>of</strong> Avicennia at the study sites, indicating<br />

that the flowering season is only for three months in a<br />

year. On the contrary, Wium-Andersen & Christensen<br />

(1978) reported that in A. marina, flowering occurs<br />

during April–May. Further, Mulik & Bhosale (1989)<br />

noted that the flowering in this species is from April–<br />

September. These authors also mentioned that the<br />

flowering occurs during March-July in A. <strong>of</strong>ficinalis.<br />

The variation in the schedule and length <strong>of</strong> flowering<br />

season in these species may be a response to local<br />

environmental conditions and to avoid competition for<br />

the available pollinators depending on the flowering<br />

seasons and population size <strong>of</strong> the constituent plant<br />

species which vary with each mangrove forest. In all<br />

the three species, the flowers are borne either in terminal<br />

or axillary inflorescences. But, the average number <strong>of</strong><br />

flowers per inflorescence varies with each species; it<br />

is the highest in A. alba, moderate in A. marina and<br />

the least in A. <strong>of</strong>ficinalis. This flower production<br />

rate at inflorescence level may serve as an important<br />

taxonomic characteristic for the identification <strong>of</strong> these<br />

three species.<br />

In all, the flowers are strongly protandrous and the<br />

stamens with dehisced anthers over-arch the stigma.<br />

<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Threatened</strong> <strong>Taxa</strong> | www.threatenedtaxa.org | <strong>December</strong> <strong>2012</strong> | 4(15): 3377–3389<br />

3385

Pollination biology <strong>of</strong> Avicennia<br />

The stigma shows post-anthesis growth. It is erect and<br />

seated in the center <strong>of</strong> the flower in A. alba and A.<br />

marina while it is bent and situated below the adaxial<br />

corolla lobe in A. <strong>of</strong>ficinalis. The erect stigma does<br />

not change its orientation throughout the flower life in<br />

A. alba and A. marina while the bent stigma becomes<br />

erect on day 3. The stigma is bifid and appressed on<br />

the day <strong>of</strong> anthesis in all the three species; it remains<br />

in the same state also on day 2 in A. <strong>of</strong>ficinalis.<br />

The stigma commences receptivity by diverging in<br />

dorsi-ventral plane; it is receptive on day 2 and 3 in<br />

A. alba and A. marina, and on day 3, 4 and 5 in A.<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficinalis. The timing <strong>of</strong> commencement <strong>of</strong> stigma<br />

receptivity in A. <strong>of</strong>ficinalis strongly contradicts with<br />

an earlier report by Reddi et al. (1995) that the stigma<br />

attains receptivity three hours after anthesis with the<br />

bent stigma becoming erect. In A. <strong>of</strong>ficinalis, stigma<br />

behaviour is more advanced towards achieving crosspollination.<br />

In all the three species, self-pollination <strong>of</strong><br />

individual flowers is unlikely on the day <strong>of</strong> anthesis<br />

due to protandry but the stamens with dehisced anthers<br />

over-arching the stigma may facilitate the fall <strong>of</strong><br />

pollen on the receptive stigma when the latter attains<br />

receptivity. In effect, self-pollination may occur and<br />

the same is evidenced through fruit set in bagged<br />

flowers without manual self-pollination. Further, the<br />

sequence and synchrony <strong>of</strong> flowering, and pollinator<br />

behaviour at tree level contribute to geitonogamy<br />

(Clarke & Meyerscough 1991). Hand-pollination<br />

results indicate that it is self-compatible and fruit set<br />

occurs through autogamy, geitonogamy and allogamy.<br />

The hermaphroditic flowers with strong protandry<br />

and long period <strong>of</strong> flower life in these species suggest<br />

that they are primarily adapted for cross-pollination.<br />

Clarke & Meyerscough (1991) also reported that A.<br />

marina is protandrous, self-compatible and selfpollinating<br />

but the fruits resulting from spontaneous<br />

self-pollination showed a higher rate <strong>of</strong> maternal<br />

abortion reflecting an inbreeding depression. Coupland<br />

et al. (2006) reported that in A. marina, autogamy<br />

is most unlikely and emphasized the importance <strong>of</strong><br />

pollen vectors to the reproductive success. This report<br />

is not in agreement with the results obtained in handpollination<br />

experiments on A. marina. Primack et al.<br />

(1981) suggested that protandry promotes out-crossing<br />

in mangroves, and that insect pollination facilitates<br />

it. They also suggested that geitonogamy in coastal<br />

colonizing plants would allow some fruit set in isolated<br />

A.J.S. Raju et al.<br />

colonizing plants, and thereafter the proportion <strong>of</strong> such<br />

pollinations would decline as pollen is transferred<br />

between plants. Pollen transfer between plants in such<br />

situations would still result in sibling mating. However,<br />

this is counteracted by dispersal <strong>of</strong> propagules,<br />

canopy suppression <strong>of</strong> seedlings and irregular yearly<br />

flowering among trees in close proximity. Clarke &<br />

Meyerscough (1991) reported that in A. marina, some<br />

trees flower and fruit every year while some others do<br />

not flower every year. Those with complete canopy<br />

crops did not produce another large crop the following<br />

year. A similar pattern observed within a tree where<br />

fruit is produced on one branch and in the following<br />

year heavy flowering shifts to another branch. In<br />

the present study, all the three species <strong>of</strong> Avicennia<br />

flowered annually and the flowering is uniform on<br />

all branches within a tree. The study suggests that<br />

annual mass flowering, protandry, self-compatibility<br />

and self-pollination ability are important adaptations<br />

for Avicennia species to successfully colonize new<br />

areas and expand their distribution range as pioneer<br />

mangroves.<br />

All the three species <strong>of</strong> Avicennia are hermaphroditic<br />

and have similar floral architecture. In all, the flowers<br />

are <strong>of</strong> open type and shallow with small aliquots <strong>of</strong><br />

nectar which is exposed to rapid evaporation resulting<br />

in increased nectar sugar concentration. Corbet<br />

(1978) considered these characteristics as adaptations<br />

for fly pollination. Hexose-rich nectar is present in<br />

A. alba and A. marina while sucrose-rich nectar in A.<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficinalis. Hexose-rich nectar is the characteristic <strong>of</strong><br />

fly- and short-tongued bee-flowers while sucrose-rich<br />

nectar is the characteristic <strong>of</strong> wasps and butterflies<br />

(Baker & Baker 1982; 1983). The nectar sugar<br />

concentration is high and ranged from 38–40 % in<br />

all the three Avicennia species. Cruden et al. (1983)<br />

reported that high nectar sugar concentration is the<br />

characteristic <strong>of</strong> bee-flowers while low nectar sugar<br />

concentration is the characteristic <strong>of</strong> butterfly-flowers.<br />

Baker & Baker (1982) reported that the floral nectar is<br />

an important source <strong>of</strong> amino acids for insects. Dadd<br />

(1973) stated that insects require ten essential amino<br />

acids <strong>of</strong> which arginine, lysine, threonine and histidine<br />

are present in the nectar <strong>of</strong> A. <strong>of</strong>ficinalis. He also<br />

reported that proline and glycine are essential amino<br />

acids for some insects; these two amino acids are also<br />

present in the nectar <strong>of</strong> A. <strong>of</strong>ficinalis. He further stated<br />

that other amino acids such as alanine, aspartic acid,<br />

3386<br />

<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Threatened</strong> <strong>Taxa</strong> | www.threatenedtaxa.org | <strong>December</strong> <strong>2012</strong> | 4(15): 3377–3389

Pollination biology <strong>of</strong> Avicennia<br />

glutamic acid, glycine and serine while not essential<br />

do increase insect growth. All these amino acids are<br />

also present in the nectar <strong>of</strong> A. <strong>of</strong>ficinalis. Shiraishi<br />

& Kuwabara (1970) reported that proline stimulates<br />

salt receptor cells in flies. Goldrich (1973) reported<br />

that histidine elicits a feeding response while glycine<br />

and serine invoke an extension <strong>of</strong> the proboscis.<br />

The nectars <strong>of</strong> A. alba and A. marina have not been<br />

analyzed for amino acids and hence this aspect has not<br />

been discussed.<br />

The flowers <strong>of</strong> all the three species <strong>of</strong> Avicennia<br />

with differences in their structural and functional<br />

characteristics as stated above have been able to<br />

attract different classes <strong>of</strong> insects—bees, wasps, flies<br />

and butterflies. Of these, bees while collecting pollen<br />

and nectar, and all other insects while collecting nectar<br />

effected pollination and their ability to carry pollen<br />

has been evidenced in their body washings. Flies<br />

are known as short distance fliers and such behaviour<br />

largely results in autogamy or geitonogamy. Since<br />

these flies visit the flowers as large groups, there is<br />

automatically a competition for the available nectar<br />

which is secreted in small aliquots on the petals <strong>of</strong><br />

all the three Avicennia species. In consequence, they<br />

shift from tree to tree in search <strong>of</strong> nectar forage and<br />

in the process they contribute to both self- and crosspollination.<br />

All other insects are habitual long-distance<br />

fliers and effect both self- and cross-pollination. An<br />

earlier report by Subba Reddi et al. (1995) showed that<br />

only bees and flies are the pollinators <strong>of</strong> A. <strong>of</strong>ficinalis<br />

at the study sites. Tomlinson (1986) mentioned that<br />

Avicennia flowers are bee-pollinated. In Australia,<br />

A. marina is pollinated by ants, wasps, bugs, flies,<br />

bee-flies, cantharid beetles and moths (Clarke &<br />

Meyerscough 1991).<br />

Tomlinson (1986) documented that A. alba, A.<br />

marina and A. <strong>of</strong>ficinalis have very similar flowers<br />

and hence may well be served by the same class, if<br />

not by the same species <strong>of</strong> pollinators; when these<br />

species grow together, there is evidence <strong>of</strong> nonsynchrony<br />

in flowering times, which might minimize<br />

the competition for pollinators (probably bees) and at<br />

the same time spread the availability <strong>of</strong> nectar over<br />

a more extended period. In the present study, these<br />

plant species grow together, flower synchronously<br />

but served by the same classes <strong>of</strong> insects. There is<br />

no competition for pollen among different classes <strong>of</strong><br />

insects since only bees collect pollen while all other<br />

A.J.S. Raju et al.<br />

classes <strong>of</strong> insects collect only nectar. Fly pollinators<br />

with their swarming behaviour at the flowers may<br />

enable the plant species to set fruit to the extent<br />

possible. Flies and bees are usually consistent and<br />

reliable when compared to wasps and butterflies.<br />

Therefore, the study shows flies and bees play an<br />

important role in the success <strong>of</strong> sexual reproduction<br />

in all the three species <strong>of</strong> Avicennia. Despite being<br />

pollinated by different classes <strong>of</strong> insect pollinators and<br />

having the ability to self-pollinate even in the absence<br />

<strong>of</strong> insect activity as evidenced in bagged flowers,<br />

the natural fruit set stands at 42–58 % in these plant<br />

species. This low fruit set could be due to maternal<br />

abortion <strong>of</strong> self-pollinated fruits as reported by Clarke<br />

& Meyerscough (1991), non-availability <strong>of</strong> sufficient<br />

pollen to receptive stigmas due to pollen feeding<br />

activity <strong>of</strong> bees and the nutritional resource constraint<br />

to the maternal parent. Coupland et al. (2006) while<br />

reporting on fruit set aspects <strong>of</strong> A. marina in Australia<br />

mentioned that fruit set is not pollinator limited but<br />

resource limited.<br />

In Avicenniaceae, the flowers have been reported to<br />

contain four ovules (Tomlinson 1986). In the present<br />

study, all the three species <strong>of</strong> Avicennia are 4-ovuled<br />

but only one ovule develops into mature seed in<br />

fertilized and fruited flowers as in Rhizophoraceae. The<br />

production <strong>of</strong> one-seeded fruits may be due to maternal<br />

resource constraint or maternal regulation <strong>of</strong> seed set.<br />

Fruits grow and mature within 5–6 weeks in A. alba<br />

and within 4 weeks in the other two Avicennia species.<br />

The duration <strong>of</strong> fruit maturation is not in agreement<br />

with the report <strong>of</strong> Wium-Andersen & Christensen<br />

(1978) who stated that the development from flower<br />

bud to mature fruit takes a few months. The calyx is<br />

persistent in all the three species but it does not expand<br />

to enclose the growing fruit. Therefore, the calyx has<br />

no role in sheltering or protecting the fruit. As the fruit<br />

is a leathery capsule, it does not require any protection<br />

from the calyx.<br />

The single seed formed in the fruit is not dormant<br />

and germinates immediately to produce chlorophyllous<br />

seedling which remains within the fruit, while still<br />

on the maternal parent. This is a characteristic <strong>of</strong><br />

“crypto-viviparous” species; similar situation exists<br />

in the genera such as Aegiceras, Aegialitis, Nypa and<br />

Pelliciera (Tomlinson 1986). In all these species, fruit<br />

is the propagule; the seedling occupies the fruit cavity.<br />

The chlorophyllous seedling actively photosynthesizes<br />

<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Threatened</strong> <strong>Taxa</strong> | www.threatenedtaxa.org | <strong>December</strong> <strong>2012</strong> | 4(15): 3377–3389<br />

3387

Pollination biology <strong>of</strong> Avicennia<br />

while the maternal parent supplies the water and<br />

necessary nutrients (Selvam & Karunagaran 2004). In<br />

Avicennia species, the propagules are small, light and<br />

the entire embryo is buoyant after detachment from<br />

the maternal parent. Gradually, the fruit pericarp is<br />

lost exposing the leathery succulent cotyledons to tidal<br />

water. Rabinowitz (1978) reported that A. marina has<br />

an absolute requirement for a stranding period in order<br />

to establish since its propagules always float in tidal<br />

water. He also felt that the propagules must have<br />

freedom from tidal disturbance in order to take hold<br />

in the soil. In consequence, this species is restricted<br />

to the higher ground portions <strong>of</strong> the swamp where the<br />

tidal inundation is less frequent. In the present study,<br />

Avicennia species exhibit self-planting strategy at low<br />

tide and stranding strategy at high tide. However,<br />

their seedlings disperse widely in tidal water but<br />

establishment is mainly stationed in the polyhaline<br />

zone. Duke et al. (1998) reported that Avicennia<br />

seedlings disperse widely and are genetically uniform<br />

throughout their range. In the study areas, genetic<br />

studies are required to know whether all the three<br />

species studied are genetically uniform. When the<br />

seedlings settle, radicle penetrates the sediment before<br />

the cotyledons unfold. The first formal leaves appear<br />

one month after germination and the second pair one to<br />

two months (Wium-Andersen & Christensen 1978).<br />

Coupland et al. (2006) reported that Avicennia<br />

propagules are a rich source <strong>of</strong> nutrients and attract a<br />

diverse range <strong>of</strong> insect predators which in turn influence<br />

the rate <strong>of</strong> seedling maturation. Resource constraints<br />

and insect predation on developing fruit and seedling<br />

may both act to reduce fruit set. In A. marina and A.<br />

germinans, the seedlings tend to be high in nutritive<br />

value and have relatively few chemical defenses<br />

(Smith 1987; McKee 1995). These species tend to<br />

exhibit a pattern <strong>of</strong> very rapid initial predation (Allen<br />

et al. 2003). In the present study, seedling predation<br />

has been evidenced in A. alba and A. marina only; in<br />

both the species, the Rose-ringed Parakeet Psittacula<br />

krameri attacks propagules prior to their detachment<br />

from the maternal parent. Seedling predation by crabs<br />

after detachment from the maternal parent may be<br />

expected since different species <strong>of</strong> crabs have been<br />

found in the study areas. Therefore, seedling predation<br />

may reduce the success <strong>of</strong> seedling establishment in<br />

all the three species <strong>of</strong> Avicennia.<br />

References<br />

A.J.S. Raju et al.<br />

Allen, J.A., K.W. Krauss & R.D. Hauff (2003). Factors<br />

limiting the intertidal distribution <strong>of</strong> the mangrove species<br />

Xylocarpus granatum. Oecologia 135: 110–121.<br />

Baker, H.G. & I. Baker (1973). Some anthecological aspects<br />

<strong>of</strong> evolution <strong>of</strong> nectar-producing flowers, particularly amino<br />

acid production in nectar, pp. 243–264. In: Heywood, V.H.<br />

(ed.). Taxonomy and Ecology, Academic Press, London.<br />

Baker, H.G. & I. Baker (1982). Chemical constituents <strong>of</strong><br />

nectar in relation to pollination mechanisms and phylogeny,<br />

pp. 131–171. In: Nitecki, H.M. (ed.). Biochemical aspects<br />

<strong>of</strong> Evolutionary Biology, University <strong>of</strong> Chicago Press,<br />

Chicago.<br />

Baker, H.G. & I. Baker (1983). A brief historical review <strong>of</strong> the<br />

chemistry <strong>of</strong> floral nectar, pp. 126–152. In: Bentley, B. & T.<br />

Elias (eds.). The Biology <strong>of</strong> Nectaries, Columbia University<br />

Press, New York.<br />

Clarke, P.J. & P.J. Meyerscough (1991). Floral biology and<br />

reproductive phenology <strong>of</strong> Avicennia marina in south<br />

eastern Australia. Australian <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> Botany 39: 283–<br />

293.<br />

Corbet, S.A. (1978). Nectar, insect visits, and the flowers<br />

<strong>of</strong> Echium vulgare, pp. 21–30. In: Richards, A.J. (ed.).<br />

The Pollination <strong>of</strong> Flowers by Insects, Academic Press,<br />

London.<br />

Coupland, G.T., I.P. Eric & K.A. McGuinness (2006).<br />

Floral abortion and pollination in four species <strong>of</strong> tropical<br />

mangroves from northern Australia. Aquatic Botany 84:<br />

151–157.<br />

Cruden, R.W. (1977). Pollen-ovule ratios: a conservative<br />

indicator <strong>of</strong> breeding systems in flowering plants. Evolution<br />

31: 32–46.<br />

Cruden, R.W., H.M. Hermann & S. Peterson (1983). Patterns<br />

<strong>of</strong> nectar production and plant-pollinator co-evolution, pp.<br />

80–125. In: Bentley, B. & T. Elias (eds.). The Biology <strong>of</strong><br />

Nectaries. Columbia University Press, New York.<br />

Dadd, R.H. (1973). Insect nutrition: current developments and<br />

metabolic implications. Annual Review <strong>of</strong> Entomology 18:<br />

881–420.<br />

Dafni, A., P.G. Kevan & B.C. Husband (2005). Practical<br />

Pollination Biology. Enviroquest Ltd., Ontario, 590pp.<br />

Duke, N.C. (1991). A systematic revision <strong>of</strong> the mangrove<br />

genus Avicennia (Avicenniaceae) in Australasia. Australian<br />

<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> Systematic Botany 4: 299–324.<br />

Duke, N.C. (1992). Mangrove floristics and biogeography, pp.<br />

63–100. In: Robertson, A.J. & D.M. Alongi (eds.). Tropical<br />

Mangrove Ecosystems, Coastal and Estuarine Studies<br />

Series. American Geographical Union, Washington.<br />

Duke, N.C., A.H.B. John, J.A. Goodall & E.R. Ballment<br />

(1998). A genetic structure and evolution <strong>of</strong> species in the<br />

mangrove genus Avicennia (Avicenniaceae) in the Indowest<br />

pacific. Evolution 52: 1612–1626.<br />

Ewusie, J.Y. (1980). Tropical Ecology. Heinemann Educational<br />

Books Ltd., London, 205pp.<br />

Goldrich, N.R. (1973). Behavioural responses <strong>of</strong> Phormia<br />

3388<br />

<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Threatened</strong> <strong>Taxa</strong> | www.threatenedtaxa.org | <strong>December</strong> <strong>2012</strong> | 4(15): 3377–3389

Pollination biology <strong>of</strong> Avicennia<br />

regina (Meigen) to labellar stimulation with amino acids. <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> General<br />

Physiology 61: 74–88.<br />

Harborne, J.B. (1973). Phytochemical Methods. Chapman and Hall, London,<br />

302pp.<br />

McKee, K.L. (1995). Mangrove species distribution and propagule predation in<br />

Belize: An exception to the dominance-predation hypothesis. Biotropica 27: 334–<br />

345.<br />

Mulik, N.G. & L.J. Bhosale (1989). Flowering phenology <strong>of</strong> the mangroves from<br />

the west coast <strong>of</strong> Maharashtra. <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> the Bombay Natural History Society<br />

86: 355–359.<br />

Opler, P.A., G.W. Frankie & H.G. Baker (1976). Rainfall as a factor in the release,<br />

timing and synchronization <strong>of</strong> anthesis by tropical trees and shrubs. <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

Biogeography 3: 231–236.<br />

Primack, R.B., N.C. Duke & P.B. Tomlinson (1981). Floral morphology in relation<br />

to pollination ecology in five Queensland coastal plants. Austrobaileya 4: 346–<br />

355.<br />

Rabinowitz, D. (1978). Dispersal properties <strong>of</strong> mangrove propagules. Biotropica 10:<br />

47–57.<br />

Reddi, C.S., A.J.S. Raju & S.N. Reddy (1995). Pollination ecology <strong>of</strong> Avicennia<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficinalis L. (Avicenniaceae). <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> Palynology 31: 253–260.<br />

Selvam, V. & V.M. Karunagaran (2004). Ecology and Biology <strong>of</strong> Mangroves.<br />

Coastal Wetlands: Mangrove Conservation and Management. Orientation Guide<br />

1. M.S. Swaminathan Research Foundation, Chennai, 158pp.<br />

Shiraishi, A. & M. Kuwabara (1970). The effects <strong>of</strong> amino acids on the labellar hair<br />

chemosensory cells <strong>of</strong> the fly. <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> General Physiology 56: 768–782.<br />

Smith, T.J. (1987). Seed predation in relation to tree dominance and distribution in<br />

mangrove forests. Ecology 68: 266–273.<br />

Tomlinson, P.B. (1986). The Botany <strong>of</strong> Mangroves. Cambridge University Press, New<br />

York, 413pp.<br />

Wium-Andersen, S. & B. Christensen (1978). Seasonal growth <strong>of</strong> mangrove trees<br />

in southern Thailand. II. Phenology <strong>of</strong> Bruguiera cylindrica, Ceriops tagal,<br />

Lumnitzera littorea and Avicennia marina. Aquatic Botany 5: 383–390.<br />

A.J.S. Raju et al.<br />

Author Details:<br />

Pr o f. A.J. So l o m o n Ra j u is Head in the<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Environmental Sciences, Andhra<br />

University, Visakhapatnam. He is presently<br />

working on endemic and endangered plant<br />

species in southern Eastern Ghats forests with<br />

financial support from UGC and MoEF, and on<br />

mangroves <strong>of</strong> Andhra Pradesh with financial<br />

support from MoEF.<br />

Dr. P.V. Su b b a Ra o is Assistant Director working<br />

in the Ministry <strong>of</strong> Environment & Forests,<br />

Government <strong>of</strong> India, New Delhi.<br />

Mr. Ra j e n d r a Ku m a r is Research Officer<br />

working in the Ministry <strong>of</strong> Environment &<br />

Forests, Government <strong>of</strong> India, New Delhi, and<br />

also pursuing PhD (part-time) under Pr<strong>of</strong>. A.J.<br />

Solomon Raju.<br />

Dr. S. Ra m a Mo h a n is Assistant Director,<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Horticulture, Government <strong>of</strong><br />

Andhra Pradesh. He has worked under Pr<strong>of</strong>.<br />

A.J. Solomon Raju for PhD during which he did<br />

part <strong>of</strong> the work reported in this paper.<br />

<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Threatened</strong> <strong>Taxa</strong> | www.threatenedtaxa.org | <strong>December</strong> <strong>2012</strong> | 4(15): 3377–3389<br />

3389

JoTT Sh o r t Co m m u n ic a t i o n 4(15): 3390–3394<br />

Philodendron williamsii Hook. f. (Araceae), an endemic<br />

and vulnerable species <strong>of</strong> southern Bahia, Brazil used for<br />

local population<br />

Luana S.B. Calazans 1 , Erica B. Morais 2 & Cassia M. Sakuragui 3<br />

1,3<br />

Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, CCS, Instituto de Biologia, Departamento de Botânica, Av. Carlos Chagas Filho, 373 -<br />

Sala A1-084 - Bloco A, CEP 21941-902, Ilha do Fundão, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil<br />

2<br />

Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Museu Nacional, Departamento de Botânica, Quinta da Boa Vista, CEP 20940-040, Rio<br />

de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil<br />

Emails: 1 luanasbcalazans@gmail.com (corresponding author), 2 ericcabarroso@gmail.com, 3 cmsakura12@gmail.com<br />

Abstract: An updated description and information on ecology,<br />

geographical distribution, ethnobiology, uses and conservation<br />

<strong>of</strong> Philodendron williamsii are presented here. The species has<br />

a restricted geographical distribution and the roots <strong>of</strong> its natural<br />

populations are widely extracted to be used for local handicraft.<br />

During the fertile period <strong>of</strong> the plant, areas where the species<br />

grow were prospected in order to collect, observe, photograph<br />

and consult people who directly use parts <strong>of</strong> the plants. Additional<br />

specimens from five herbaria were analyzed. We propose the<br />

inclusion <strong>of</strong> the species as Vulnerable based on the categories<br />

and the criteria proposed by the IUCN. Environmental education<br />

for the local extractors and the regularization <strong>of</strong> its extractive<br />

activity are suggested here.<br />

Keywords: Conservation, extractivism, imbé, southern Bahia,<br />

taxonomy.<br />

Resumo (Portuguese Abstract): São aqui apresentadas uma<br />

descrição atualizada, informações sobre a ecologia, distribuição<br />

geográfica, etnobiologia, usos e conservação de Philodendron<br />

williamsii. A espécie tem distribuição geográfica restrita e as<br />

raízes de suas populações naturais s<strong>of</strong>rem intenso extrativismo<br />

voltado para o artesanato local. Áreas do habitat natural da<br />

espécie foram visitadas durante seu período fértil com o objetivo<br />

de coletar, observar, fotografar e consultar a população local<br />

que faz uso direto da planta. Espécimes adicionais de cinco<br />

herbários foram também analisados. A inclusão da espécie na<br />

Lista Vermelha de Espécies Ameaçadas é proposta com base<br />

nas categorias e critérios da IUCN. Sugerimos a educação<br />

ambiental com os extratores locais e a regularização desta<br />

atividade para conservação da espécie.<br />

Palavras chave: conservação, extrativismo, imbé, Sul da Bahia,<br />

taxonomia.<br />

Date <strong>of</strong> publication (online): 26 <strong>December</strong> <strong>2012</strong><br />

Date <strong>of</strong> publication (print): 26 <strong>December</strong> <strong>2012</strong><br />

ISSN 0974-7907 (online) | 0974-7893 (print)<br />

Editor: Anonymity requested<br />

Manuscript details:<br />

Ms # o3124<br />

Received 16 March <strong>2012</strong><br />

Final received 01 September <strong>2012</strong><br />

Finally accepted 24 November <strong>2012</strong><br />

Citation: Calazans, L.S.B., E.B. Morais & C.M. Sakuragui (<strong>2012</strong>).<br />

Philodendron williamsii Hook. f. (Araceae), an endemic and vulnerable<br />

species <strong>of</strong> southern Bahia, Brazil used for local population. <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Threatened</strong> <strong>Taxa</strong> 4(15): 3390–3394.<br />

Copyright: © Luana S.B. Calazans, Erica B. Morais & Cassia M. Sakuragui<br />

<strong>2012</strong>. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. JoTT allows<br />

unrestricted use <strong>of</strong> this article in any medium for non-pr<strong>of</strong>it purposes,<br />

reproduction and distribution by providing adequate credit to the authors<br />

and the source <strong>of</strong> publication.<br />

Acknowledgements: We are grateful to Marco Octávio Pellegrini for the<br />

help with the images and suggestions in the manuscript, Rodrigo Theófilo<br />

Valadares for the map elaboration, the craftsmen and foresters Mr. Aderval<br />

and Mr. Gildo for the field assistance, all the people who helped us with<br />

information, Hugo Fernandes-Ferreira for the help with the ethnobiology<br />

methodology, Vitor Tenorio da Rosa for the contribution with anatomical<br />

knowledge and Ana Cecília Castro for suggestions in the manuscript.<br />

OPEN ACCESS | FREE DOWNLOAD<br />

Philodendron williamsii Hook. f. is a poorly known<br />

species <strong>of</strong> Philodendron subgenus Meconostigma<br />

(Araceae), described in 1871 from material collected<br />

by C.H. Williams in the Bahia State, probably near<br />

Salvador and has been cultivated at Kew (Mayo<br />

1991).<br />

Due to some similar morphological characters<br />

with P. stenolobum E.G. Gonç. (Gonçalves & Salviani<br />

2002), many horticulturists believe they have it in their<br />

collections, however, they actually possess specimens<br />

<strong>of</strong> the latter. Populations currently circumscribed<br />

as P. stenolobum, which is endemic to the Espírito<br />

Santo state, were treated as P. williamsii in the latest<br />

revision <strong>of</strong> the subgenus Meconostigma (Mayo 1991),<br />

since the author could not have access to the fertile<br />

material from these populations. The main differences<br />

between them lie in leaf dimensions and gynoecium<br />

morphology (Table 1 in Gonçalves & Salviani 2002).<br />

Despite its ornamental potential for landscaping, P.<br />

williamsii is rarely found in live collections due to the<br />

difficulty <strong>of</strong> its propagation and cultivation.<br />

The aim <strong>of</strong> the work is to give new information on<br />

3390<br />

<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Threatened</strong> <strong>Taxa</strong> | www.threatenedtaxa.org | <strong>December</strong> <strong>2012</strong> | 4(15): 3390–3394

Philodendron williamsii<br />

ecology, geographical distribution, uses, ethnobiology<br />

and conservation <strong>of</strong> P. williamsii, an endemic and<br />

threatened species from the Atlantic Forests <strong>of</strong><br />

southern Bahia.<br />

Materials and Methods<br />

Field work was carried out in February and<br />

<strong>December</strong> <strong>of</strong> 2011, searching for Philodendron<br />

species in Bahia State, specially prospecting areas <strong>of</strong><br />

Itacaré and Una, where the species grows. Special<br />

effort was made to collect the plants during the fertile<br />

period. In order to obtain information on its use by<br />

the local population, semi-structured interviews were<br />

conducted (Huntington 2000), selecting informants<br />

(craftsmen, merchants and foresters) who use parts <strong>of</strong><br />

the plants directly in their activities.<br />

To complement the description, ecological data and<br />

geographical distribution, material from the following<br />

herbaria were also analyzed: ALCB, CEPEC, HUEFS,<br />

RB, RFA (acronyms according to Thiers, constantly<br />

updated). The descriptions followed Mayo (1991),<br />

with modifications. The conservation status was<br />

proposed based on the categories and the criteria<br />

proposed by the IUCN (2010).<br />

Results and Discussion<br />

Philodendron williamsii Hook. f., Bot. Mag. 97: t.<br />