1. Hill, Lance Edward. “The Deacons for ... - Freedom Archives

1. Hill, Lance Edward. “The Deacons for ... - Freedom Archives

1. Hill, Lance Edward. “The Deacons for ... - Freedom Archives

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

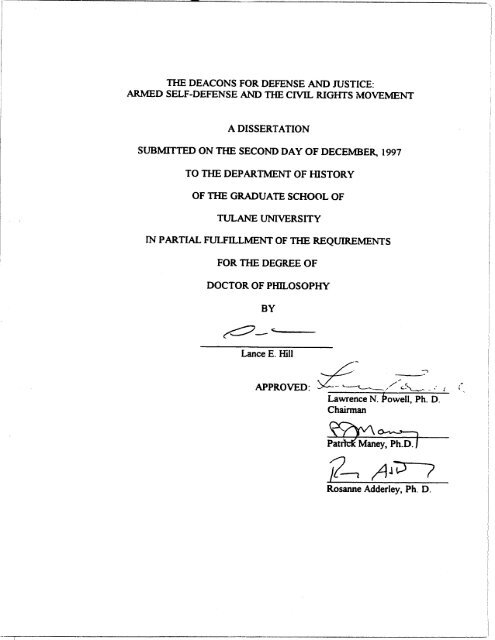

THE DEACONS FOR DEFENSE AND JUSTICE :<br />

ARMED SELF-DEFENSE AND THE CIVIIr RIGHTS MOVEMENT<br />

A DISSERTATION<br />

SUBMITTED ON THE SECOND DAY OF DECEMBER, 1997<br />

TO THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY<br />

OF THE GRADUATE SCHO(1L OF<br />

TULANE UNIVERSITY<br />

IN PARTIAL FULFII.LMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS<br />

FOR THE DEGREE OF<br />

DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY<br />

BY<br />

<strong>Lance</strong> E . <strong>Hill</strong><br />

APPROVED : __ ~--~--~~,,~~`~. _<br />

Lawrence N . owell, Ph . D .<br />

Chairman<br />

v<br />

Pa~aney, Ph.D .<br />

Rosanne Adderley, Ph . D .

UMI Number : 9817924<br />

Copyright 1997 by<br />

<strong>Hill</strong> <strong>Lance</strong> <strong>Edward</strong><br />

All rights reserved .<br />

U14II Micro<strong>for</strong>m 9817924<br />

Copyright 1998, by Ul4Q Company . All rights reserved .<br />

This micro<strong>for</strong>m edition is protected against unauthorized<br />

copying under Title 17, United States Code .<br />

300 North Zeeb Road<br />

Atut Arbor, MI 48103

© Copyright by <strong>Lance</strong> <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Hill</strong>, 1997<br />

All rights reserved

TABLE OF CON71NTS<br />

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . iv<br />

CHAPTER<br />

1 . Beginnings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .I<br />

The early Civil Rights Movement in Jonesboro, Louisiana<br />

2 . The Art of Self-Defense . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29<br />

The beginnings of armed self-defense in Jonesboro<br />

3 . The Justice and Defense Club . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47<br />

The <strong>Deacons</strong> <strong>for</strong> Defense and Justice <strong>for</strong>m in Jonesboro<br />

4. The New York Times . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .64<br />

First national publicity <strong>for</strong> the <strong>Deacons</strong><br />

5 . NotSelma . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .84<br />

The spring 1965 campaign in Jonesboro<br />

6. The Magic City . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .I09<br />

The early Civil Rights Movement in Bogalusa, Louisiana<br />

7. The Bogalusa Chapter . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 137<br />

The <strong>for</strong>mation of the Bogalusa <strong>Deacons</strong> chapter<br />

8 . The Spring Campaign . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 159<br />

The <strong>Deacons</strong> challenge the Klan in Bogalusa

9 . With a Single Bullet . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 197<br />

The Klan vanquished in Bogalusa<br />

10 . Creating the Myth . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 232<br />

The <strong>Deacons</strong>' changing media image<br />

11 . Expanding Through the South . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 262<br />

<strong>Deacons</strong> chapters established in Louisiana<br />

12 . Mississippi and Beyond . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 297<br />

<strong>Deacons</strong> chapters in Mississippi and the South<br />

13 . Up-South . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .340<br />

Organizing ef<strong>for</strong>ts in the North<br />

14 . Foundering in the North . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 371<br />

The Chicago chapter<br />

15 . A Long Time . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . : : . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .407<br />

Bogalusa events from fall 1965 to 1967<br />

BIBLIOGRAPHY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .433

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS<br />

I thank my dissertation advisor, Lawrence N. Powell, <strong>for</strong> his indispensable advice,<br />

perceptive criticism, and steadfast encouragement . Patrick Maney and Rosanne Adderley<br />

also offered valuable insights . Many others provided useful suggestions on research<br />

resources, including Clarence Mohr and Joe Caldwell .<br />

I am indebted to Gwendolyn Midlo Hall who generously allowed me to consult<br />

her research papers on the <strong>Deacons</strong> <strong>for</strong> Defense and Justice at the Am.istad Research<br />

Center, and arranged an intervie"~r with Deacon member Henry Austin. I also benefitted<br />

from the kind assistance ofthe staffs at the Special Collections division of the Tulane<br />

University Library, Amistad Research Center, and the Wisconsin State Historical Society .<br />

This dissertation would not have been possible had it not been <strong>for</strong> the members of<br />

the <strong>Deacons</strong> <strong>for</strong> Defense and Justice who shared with me their stories and wisdom .<br />

Finally, I am deeply grateful to my wife, Eileen San Juan, who provided years of<br />

intellectual companionship and moral support, and lent her critical eye to reading this<br />

manuscript. This dissertation is dedicated to her.

Chapter One<br />

Beginnings<br />

Paul Farmer brought his pistol . The President of the White Citizens Council<br />

was standing in the middle of the street along with several o~her members of the Citizens<br />

Council as well as Ku Klux Klan members . It was the Autumn of 1966 in the small<br />

paper mill town of Bogalusa, Louisiana .<br />

Itoyan Bums, a black barber and civil rights leader, knew why the Klan was<br />

there . They were waiting <strong>for</strong> the doors to open at Bogalusa Junior High . The school had<br />

recently been integrated and white students had been harassing and brutalizing black<br />

students with impunity . "They were just stepping on them, and spitting on them and<br />

hitting them," recalls Burris, and the black students "wasn't doing anything back ." In the<br />

past Burris had counseled the black students to remain nonviolent . Now he advised a<br />

new approach . "I said anybody hit you, hit back . Anybody step on your feet, step back .<br />

Anybody spit on you, spit back."'<br />

The young black students heeded Bums' advice . Fights between black and<br />

white students erupted throughout the day at the school . Now Paul Farmer and his band<br />

'Royan Burris, interview by author, 7 March 1989, Bogalusa, Louisiana, tape<br />

recording. The account ofthis incident is taken from Ibid . ; Louisiana Weekly, 24<br />

September 1966 ; and Times-Picayune, 14 September 1966 . Tension was exacerbated at<br />

the school by a rumor that civil rights activist James Meredith had been invited to speak<br />

at the school . See Lester Sobel, ed ., Civil Rights 1960-66 (New York : Facts on File,<br />

1976), p . 407 .

of Klansmen had arrived with guns, prepared to intervene . Their presence was no idle<br />

threat ; whites had murdered two black men in the mill town in the past two years,<br />

including a black sheriff's deputy .<br />

But Farmer had a problem. Standing in the street, only a few feet from the Klan,<br />

was a tine of grim and unyielding black men . They were members of the <strong>Deacons</strong> <strong>for</strong><br />

Defense and Justice, a black self-defense organization that had already engaged the Klan<br />

in several shooting skirmishes . The two groups faced off the Klan on one side, the<br />

<strong>Deacons</strong> on the other .<br />

After a few tense moments the police arrived and attempted to defuse the<br />

volatile situation . They asked the <strong>Deacons</strong> to leave first, but the black men refused .<br />

Bums recalls the <strong>Deacons</strong>' terse response to the police request . "We been leaving first<br />

all of our lives," said Bums . "This time we not going in peace." Infuriated by the<br />

<strong>Deacons</strong>' defiance, Paul Farmer suddenly pulled his pistol . In a reflex response, one of<br />

the <strong>Deacons</strong> drew his revolver and in an instant there were halfa dozen pistols waving<br />

menacingly in the air. Surveying the weapons arrayed against them, the band of<br />

Klansmen grudgingly pocketed their weapons and departed .<br />

The <strong>Deacons</strong> <strong>for</strong> Defense and Justice had faced death and never flinched .<br />

"From that day <strong>for</strong>ward," says Bums, "we didn't have too many more problems ."~<br />

=Bums, <strong>Hill</strong> interview .

In the nineteenth century the pine hills of North Louisiana were a hostile refuge<br />

<strong>for</strong> the poor and dispossessed . Following the Civil War, legions of starving and<br />

desperate whites were driven into the pine hills by destruction, drought and depleted soi :<br />

in the Southeast . They arrived to find the best alluvial land controlled by large<br />

landowners and speculators . The remaining soil was poorly suited <strong>for</strong> farming, rendered<br />

haggard and sallow by millennia ofacidic pine needles deposited on the <strong>for</strong>est floor . The<br />

lean migrants scratched the worthless sandy soil, shook their heads, and resigned<br />

themselves to the unhappy fate of subsistence farming.<br />

Upcountry whites eked out a living with a dozen acres of "corn `n `taters," a<br />

few hogs <strong>for</strong> fatback, trapping and hunting <strong>for</strong> game, and occasionally logging <strong>for</strong> local<br />

markets . Not until the turn ofthe century, when large-scale lumber industry invaded the<br />

pines, did their hopes and prospects change . Even then, prosperity was fleeting . By the<br />

1930s, the lumber leviathans had stripped the pine woods bare, leaving a residue ofa few<br />

paper and lumber mips . Those <strong>for</strong>tunate enough to find work in the pulp and paper<br />

industry watched helplessly in the 1950s and 60s as even these remaiting jobs were<br />

threatened by shrinking reserves and automation. 3<br />

These Protestant descendants of the British Isles were the latest in several<br />

generations ofwhites <strong>for</strong>ced west by a slave-based economy that consumed and depleted<br />

'Roger W . Shugg, Origins of Class Struggle in Louisiana: A Social History of<br />

While Farmers and Laborers During Slavery and After, 1810-1875(Baton Rouge :<br />

Louisiana State University Press, 1939) . The impact of automation in discussed in<br />

Robert H. Zieger, Rebuilding the Pulp and Paper Makers Union, 1933-19 ;11 (Knoxville :<br />

University of Tennessee Press, 1984) . On the role ofblacks in the paper industry, see<br />

Herbert R. Northrop, The Negro in the Paper Industry: The Racial Politics ofAmerican<br />

Industry, report no . 8, Industrial Research Unit, Department of Industry, Wharton School<br />

of Finance and Commerce, University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia : University of<br />

Pennsylvania Press, 1969) . On Bogalusa, Louisiana, see pp . 95-104.

the soil . With the end ofthe Civil War their plight was compounded by more than three<br />

million black freedmen surging across the South in search ofwork and land .<br />

Emancipation thrust blacks into merciless competition with whites <strong>for</strong> the dearth of work,<br />

land and credit .<br />

The freedmen also looked to the pines <strong>for</strong> deliverance . Blacks who remained on<br />

plantations lived in constant fear of new <strong>for</strong>ms ofbondage such as gang labor and share<br />

cropping . Thousands of dusty and tattered black families packed their belongings and<br />

trekked into the hills to escape the indignities ofdebt peonage . Like their white<br />

competitor, the freedmen sought the dignity and independence conferred by a few acres<br />

of land and the freedom to sell their labor .<br />

Through a process of social Darwitism, the pine hills were soon peopled by the<br />

most independent and self-sufficient African-Americans ; those willing to risk everything<br />

to escape economic bondage. Their passionate independence flourished in the hills as<br />

they worked as self-employed timber cutters and log haulers . By the middle of the<br />

twentieth century many of their descendants had left the land, drawn to the small<br />

industrial towns that offered decent wages in the lumber and paper mills .<br />

From the end of the Civil War through the 1960s these two fiercely independent<br />

communities, black and white, traveled separate yet parallel paths in the pine hills of<br />

North Louisiana . In the summer of 1964, in the small town ofJonesboro, these two<br />

worlds would finally cross paths-as well as swords .<br />

Jonesboro, Louisiana was one ofthe dozens ofmakeshift mill-towns that sprang<br />

up as Eastern businesses rushed to mine the vast timber spreads of Louisiana .

Incorporated in 1903, the town was little more than an appendage to a saw mill--crude<br />

shacks storing the human machinery of industry .<br />

By the 1960s Jonesboro lived in the shadow ofthe enormous Continental Can<br />

Company paper mill located in Hodge, a small town on the outskirts ofJonesboro . The<br />

New York-based company produced container board and kraft paper at the Hodge facility<br />

and employed more than 1,500 whites and 200 blacks . In addition, many blacks found<br />

employment at the OGn Mathieson Chemical Company . Those blacks who were not<br />

<strong>for</strong>tunate enough to find work in the paper mill labored as destitute woodcutters and tog<br />

haulers on the immense timber land holdings owned by Continental Can . ;<br />

Almost one-third ofJonesboro's 3,848 residents were black . Though by<br />

Southern standards Jonesboro's black community was prosperous, poverty and ignorance<br />

were still rampant . Nearly eight out ofevery ten black families lived in poverty . Ninety<br />

seven percent ofblacks over the age oftwenty-five had never completed a high school<br />

education . The "black quarters" in Jonesboro and Hodge consisted of dilapidated<br />

clapboard shacks, with cracks in the walls that whistled in the bitter winter wind. Human<br />

waste ran into the dirt streets <strong>for</strong> want of a sewerage system . Unpaved streets with exotic<br />

names like "Congo" and "Tarbottom" alternated between being dust storms and<br />

impassable rivers ofmud . s<br />

`Daniel Mitchell to Bonnie M. Moore, "Jackson Parish and Jonesboro, Louisiana:<br />

A White Paper," [September, 1964], Jonesboro, Louisiana, Monroe Project Files, CORE<br />

Papers [hereinafter cited as CORE(Monroe)], State Historical Society of Wisconsin,<br />

Madison, [hereinafter cited as SHSW] .<br />

SCensus data cited in Ibid .

Daily life in Jonesboro painstakingly followed the rituals and conventions ofJim<br />

Crow segregation . A white person walking downtown could expect blacks to<br />

obsequiously avert their eyes and step offthe sidewalk in deference . Jobs were strictly<br />

segregated, with blacks allotted positions no higher than "broom and mop" occupations .<br />

The local hospital had an all-white staff and the paper mill segregated both jobs and<br />

toilets . Blacks were even denied the simple right to walk into the public library. 6<br />

On the surface there appeared to be few diversions from the tedium and poverty .<br />

The ramshackle "Minute Spot" tavern served as the only legal drinking establishment <strong>for</strong><br />

blacks . To Danny Mitchell, a black student organizer who arrived in Jonesboro in 1964,<br />

Jonesboro's blacks appeared to seek refi~ge in gambling and other unseemly pastimes .<br />

Mitchell, with a note ofyouthful piety, once reported to his superiors in New York that<br />

most of Jonesboro's black commutity "seeks enjoyment and relief from the frustrating<br />

Gfe they endure through marital, extramarital, and inter-marital relationships ."'<br />

But there was more to Jonesboro than sex and dice . Indeed, segregation had<br />

produced a complex labyrinth of social networks and organizations in the black<br />

community . The relatively large industrial working class preserved the independent<br />

spirit that characterized blacks in the pine woods. Like many other small mill towns,<br />

blacks in Jonesboro had created a tightly-knit community that revolved around the<br />

institutions of church and fraternal orders . In the post World War II era, black men in the<br />

South frequently belonged to several fraternal orders and social clubs, such as the Prince<br />

Hall Masons and the Brotherhood <strong>for</strong> the Protection ofElks . These <strong>for</strong>mal and in<strong>for</strong>mal<br />

6Mitchell, "White Paper ."<br />

'Ibid .

organization provided a respite from the oppressive white culture . They offered status,<br />

nurtured mutual bonds of trust, and served as schools <strong>for</strong> leadership <strong>for</strong> Jonesboro's black<br />

working and middle classes . $<br />

In the period of increased activism following World War II, most ofJonesboro's<br />

civil rights leadership emerged from the small yet significant middle class ofeducators,<br />

self-employed craftsman and independent business people (religious leaders were<br />

conspicuously absent from the ranks of the re<strong>for</strong>mers) . While segregation denied blacks<br />

many opportunities, it also created captive markets <strong>for</strong> some enterprising blacks,<br />

particularly in services that whites refused to provide them . There were twenty-one<br />

black-owned businesses in Jonesboro in 1964, including taxi companies, gas stations, and<br />

a popular skating rink . 9<br />

Jackson Parish (county), where Jonesboro is located, had a small but well<br />

organized NAACP chapter since the 1940s . In the 1950s the Louisiana NAACP was<br />

gravely damaged by a state law that required disclosure of membership . Rather than<br />

divulge their members' names and expose them to harassment, many chapters replaced<br />

the NAACP with "civic and voters leagues ." Such was the case in Jackson Parish where<br />

the NAACP became the "Jackson Parish Progressive Voters League."<br />

From its inception, the Voters League concentrated its ef<strong>for</strong>ts on voter<br />

registration and enjoyed some success . When the White Citizens Council and the<br />

Registrar of Voters conspired to purge blacks from the registration rolls in 1956, the<br />

SFor a cogent summary of the literature on black fraternal orders, see David M .<br />

Fahey, The Black Lodge in White Americu: "True Re<strong>for</strong>mer " Browne and His Economic<br />

Strategy (Dayton : Wright State University, 1994), pp . 5-12 .<br />

'Mitchell, "White Paper."

Voters League retaliated with a voting rights suit initiated by the Justice Department .<br />

The Voters League prevailed and federal courts eventually <strong>for</strong>ced the registrar to cease<br />

discriminating against blacks, to report records to the federal judiciary, and to assist black<br />

applicants in registering . By 1964 nearly 18 percent ofthe parish voters were black, a<br />

remarkably high percentage <strong>for</strong> the coral South .' °<br />

The Voters League drew its leadership primarily from the ranks ofbusinessmen<br />

and educators, such as W . C . Flannagan, E. N . Francis, J . W . Dade and Fred Hearn . W .<br />

C . Flannagan, who led the Voters League in the early 1960s, was a self-employed<br />

handyman who also published a small newsletter . E . N . Francis owned several<br />

businesses, including a funeral home, grocery store, barber shop and dry-cleaning store.<br />

J . W . Dade was, by local standards, a man ofconsiderable wealth . Dade taught<br />

mathematics at Jackson I~gh School in Jonesboro and supplemented his teaching salary<br />

with income from a dozen rental houses . Fred Hearn, another Voters League leader, was<br />

also a teacher and worked as a farmer and installed and cleaned water-wells .' `<br />

The Voters League never commanded enough votes to win elective office <strong>for</strong> a<br />

black candidate . For the most part, the Voters League was limited to delivering the black<br />

vote to white candidates in exchange <strong>for</strong> poetical favors . While political patronage<br />

offered some benefits to the black community at large, it more frequently created<br />

opportunities <strong>for</strong> personal aggrandizement . At its worse, patronage disguised greed as<br />

public service . Some of the Voters League's critics felt that its leaders were principally<br />

' °Ibid .<br />

"Ibid . ; Frederick Douglas Kirkpatrick, Interview by Gwendolyn Midlo Hall, 31<br />

October 1977, New York, transcript notes, Gwendolyn 11~idlo Hall Papers (hereinafter<br />

cited as GMEI,P), Amistad Research Center, Tulane University, New Orleans, Louisiana<br />

(hereinafter cited as ARC) .

interested in gaining personal favors from politicians, and there was credence to the<br />

charge .'=<br />

In truth, the white political establishment offered a tempting assortment of<br />

patronage rewards to compliant black leaders in an ef<strong>for</strong>t to discourage them from<br />

disruptive civil rights protests. Inducements included positions in government and public<br />

education, ranging from school bus drivers to school administrators . White political<br />

patronage bought influence and loyalty in the black community . The practice testified to<br />

the fact that white domination rested on more than repression and fear : it depended on<br />

consent by a segment of the black middle class . Conflicts over segregation were to be<br />

resolved by gentlemen behind closed doors . Time and again, civil rights activists in<br />

Louisiana found the black middle class and clergy to be significant obstacles to<br />

organizing . One activist in East Felicana Parish reported that the lack ofinterest in voter<br />

registration in 1964 could be attributed to, among other things, the "General fear-<br />

inducing activity ofthe very active commutity of Toms . Every move we make is<br />

broadcast by them to the whole town<br />

."` s<br />

Indeed, the mass community meeting which became popular during the civil<br />

rights movement, was, in part, employed to limit the opportunity <strong>for</strong> middle-class leaders<br />

to make self-serving compromises . Plebiscitary democrac;~ guaranteed that all<br />

` 2Ibid . ; Mitchell, "White Paper ." The clientelist relationship between black<br />

political machines and the white power structure was noted early on by Gunnar Myrdal . j<br />

Gunnar Myrdal, An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem andModern Democracy<br />

(New York : Harper and Brothers, 1944), pp . 498-9 .<br />

` s "Weekly Report - August 1 - August 4," [August, 1964], Clinton, Louisiana,<br />

box 4, folder 13, Southern Regional Office, CORE papers [hereinafter cited as<br />

CORE(SRO)], SHSW.

agreements had to pass muster with the black rank-and-file : the working class, the poor,<br />

and the youth .<br />

There were good reasons <strong>for</strong> the suspicions exhibited by the rank-and-file .<br />

Black leadership was more complex and divided than the undifferentiated, united image<br />

reflected in the popular historical myth ofthe civil rights movement . The movement did<br />

not march in unison and speak with one voice. The black community had its share of<br />

traitors, rascals, and ordinary fools . In general, though, the leaders of the Voters League<br />

in Jonesboro were honorable men who had the community's interests at heart .<br />

hlonetheless, it was difficult <strong>for</strong> the Voters League to generate enthusiasm <strong>for</strong> voting<br />

rights when the ballot benefitted only a handful of elite blacks in the community . For<br />

most black voters in Jonesboro, elections offered tittle more than an Hobson's choice<br />

between racism and racism.<br />

The role ofthe black church in Jonesboro also contradicts the popular historical<br />

picture of the period . Deep divisions existed between the black clergy and the movement<br />

in Jonesboro . Only one church in Jonesboro, Pleasant Grove Baptist Church, initially<br />

supported the movement . Pleasant Grove had a highly active and concerned membership,<br />

led by Henry and Ruth Amos who operated a gas station, and Percy Lee Brad<strong>for</strong>d, a cab<br />

driver and mill worker . The dearth of civil rights church leaders in Jonesboro was no<br />

anomaly. While the clergy played an important role in larger cities in the South, the<br />

pattern in small towns was markedly different . In the outback, the black clergy's attitude<br />

toward the movement ranged from indifference to outrigh~ hostility . Indeed, the clergy's<br />

10

conservative stance frequently made them the target ofpretest by black youth in<br />

Jonesboro and elsewhere in Louisiana . ` j<br />

The conservative character ofrural black clergy owed to several factors . Church<br />

buildings were vulnerable to arson in retaliation <strong>for</strong> civil rights activities (churches in the<br />

South were frequently located outside of town in remote, unguarded areas) . It was<br />

common <strong>for</strong> insurance companies to cancel insurance on churches that had been active in<br />

the movement . Moreover, black ministers depended on good relationships with whites to<br />

obtain loans <strong>for</strong> the all-important "brick and mortar" building projects .<br />

But the clergy's conservatism was also emblematic ofthe contradictory<br />

character of the black church . On the one hand, the church was a <strong>for</strong>ce <strong>for</strong> change. It<br />

provided a safe and nurturing sanctuary in a hostile and oppressive world . In the midst of<br />

despair, it <strong>for</strong>ged a new community, nourished racial solidarity, defined community<br />

values, and provided pride and hope .<br />

In contrast to this uplifting role, though, the black church was equally flawed by<br />

a fatalistic outlook that bred passivity and political cynicism . Fatalism is a rational and<br />

effective adaptation in reactionary times when people live on hope alone . Religion born<br />

out of oppression and powerlessness found hope in the promise ofa rewarding afterlife .<br />

For decades, the black clergy had preached the gospel of resignation and eschewed social<br />

and political re<strong>for</strong>m . Like many other religious groups, the black church Found<br />

something undignified and morally corrupting about poetics and the secular world_ The<br />

church retained elements of nineteenth-century conservative theology that regarded<br />

"Organized protests against the black clergy in Louisiana are discussed in<br />

chapters four and fifteen .<br />

11

collective human action <strong>for</strong> political advancement as unnatural and impious . Destiny was<br />

divinely ordained . `s<br />

There were exceptions to the conservative churches, and the Pleasant Grove<br />

Baptist Church in Jonesboro was one ofthese. The church had attracted several firm<br />

civil rights advocates and in late 1963 members of the Pleasant Grove Baptist Church,<br />

along with the Voters League, invited the Congress ofRacial Equality (CORE) to initiate<br />

voter registration activities in Jonesboro and Jackson Parish . CORE was part ofthe new<br />

breed of national civil rights organizations, young, energetic, and committed to<br />

nonviolent direct action . While the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC)<br />

dominated the movement in Mississippi, CORE was the principal organizing <strong>for</strong>ce in<br />

Louisiana. They had been active in Louisiana since the 1960 sit-ins and were preparing a<br />

major summer project <strong>for</strong> 1964 .`6<br />

CORE originated as a predominantly white pacifist organization, emerging out<br />

of the Fellowship ofReconciliation, a Christian pacifist group that had been active since<br />

World War I . Formed in 1942, CORE's early leaders were profoundly influenced by the<br />

nonviolent teachings of Mohandis Gandhi . At the center of their strategy was the<br />

concept ofnonviolent direct action ; moral conversion through nonviolent protest . CORE<br />

` sThe relationship of African-American Christianity to political re<strong>for</strong>m is beyond<br />

the scope ofthis dissertation . A beginning point <strong>for</strong> the inquiry, though, is Eugene D .<br />

Genovese's, Roll, Jordan Roll: The World the Slaves Made (New York : Vintage Books,<br />

1976) and, on social gospel influences, S . P . Fullinwider, The Mind andMood in Black<br />

America: Twentieth Century Thought (Homewood, Ill . : Dorsey Press, 1969) . On<br />

nineteenth century conservative theology see Henry Farnham May, Protestant Churches<br />

and Industrial America (New York : Harper and Brothers Publishers, 1949) .<br />

` 6August Meier and Elliott Rudwick, CORE: A Study in the Civil Rights<br />

Movement 19-12-1968 (New York : Ox<strong>for</strong>d University Press, 1973 ) .<br />

13

advocated direct action and militant protest, without violence or hatred against the<br />

opponent . The organization's principles prohibited members from retaliating against<br />

violence inflicted on them . CORE believed that nonviolence would convert their<br />

enemies through "love and suffering." The organization had pragmatic as well as<br />

philosophical reasons <strong>for</strong> advocating nonviolence in the South . CORE's black leaders,<br />

such as James Farmer and Bayard Rustin, feared a brutal white backlash if blacks<br />

engaged in retaliatory violence."<br />

Despite its strong commitment to racial justice and community activism, CORE<br />

had made only modest progress in the black community in the 1940s and 1950s . But in<br />

1961 it was catapulted into the ranks of national civil rights organizations through its role<br />

in the electrifying <strong>Freedom</strong> Rides . Courageous young CORE activists led integrated<br />

groups on bus rides through the South in a campaign to integrate interstate travel<br />

facilities . They braved riotous mobs, vicious beatings, firebombs and wretched jails . By<br />

1962 they had triumphed in integrating most bus travel and terminal accommodations .<br />

In 1964 CORE planned an ambitious "Louisiana Summer 1964" project,<br />

CORE's counterpart to the Mississippi <strong>Freedom</strong> Summer project . The Louisiana project<br />

was to focus on voter registration and desegregation ofpublic facilities and public<br />

accommodations . CORE had already established several local projects in Louisiana,<br />

including a beachhead in North Louisiana in Monroe, some sixty miles East of<br />

Jonesboro . Monroe's moderate NAACP leadership had invited CORE to organize the<br />

community, but CORE had little success until they linked up with more militant working<br />

class union leaders at the Olin-Mathieson paper plant . Police harassment and an<br />

"Ibid ., chap . 1 passim .<br />

13

uncooperative registrar ofvoters seriously hampered CORE's ef<strong>for</strong>ts . From the outset,<br />

the civil rights group's presence rankled the Klan, and it was not long be<strong>for</strong>e the Klan<br />

burned crosses on the lawn ofthe house where two CORC workers were staying . ` g<br />

The first CORE organizers to visit Jonesboro were representative ofthe social<br />

mix ofCORE's field staff Mike Lesser was a white Northerner with no experience in<br />

organizing in the South . In contrast, his organizing colleague, Ronnie Moore, was a<br />

black native-born Louisianian and a seasoned organizer who had joined CORE after he<br />

was expelled from Southern University <strong>for</strong> a protest in January 1962 . Moore was<br />

eventually arrested eighteen times and spent a total of six months in jail, fifty-seven of<br />

those days in solitary confinement . Beginning in January 1964, Lesser and Moore made<br />

several trips to Jonesboro to assist the Jackson Parish Civic and Voters League and local<br />

high school students in launching a voter registration campaign. Their initial success<br />

prompted CORE to assign several task-<strong>for</strong>ce workers to Jonesboro in the late Spring of<br />

1964 in preparation <strong>for</strong> the summer project ."<br />

One ofthe first arrivals <strong>for</strong> the summer project was a young black woman from<br />

Birmingham, Catherine Patterson . Patterson had been deeply moved by an experience at<br />

the George Washington Carver High School in Birmingham, where she was a classmate<br />

ofFred Shuttiesworth, Jr ., the son of Birmingham's firebrand civil rights leader, the<br />

Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth . One day young Fred, Jr. arrived at schoo! with his face<br />

badly bruised and swollen . A racist mob had mercilessly beaten Fred and his father<br />

` BNGke Lesser, "Report on Jonesboro-Bogalusa Project," March 1965, box 5,<br />

folder 5, CORE(SRO) ; Meier and Rudwick, CORE, pp . 266-267 .<br />

` 9 L.esser, "Report ."

during a demonstration . "When I heard about that, it just moved me to action," recalled<br />

Patterson two decades later. "I guess I was outraged . It's one thing to hear about it, and<br />

it's another thing to see it on television . But to see someone that you are sitting next to in<br />

class severely beaten . . . he was a child, just like I was ." =°<br />

The incident inspired Patterson to plunge into political activism, first leading<br />

SCLC demonstrations in Birmingham and later joining CORE after graduating from high<br />

school in January 1963 . Patterson was first sent to C adsden, Alabama <strong>for</strong> nine months of<br />

organizing, and then on to Atlanta <strong>for</strong> nonviolence training. At the training, Patterson<br />

met most of the team that would be assigned to Jonesboro <strong>for</strong> the Summer Project in<br />

Louisiana . Among them was Ruthie Welts, a young black woman from Baton Rouge,<br />

and the two white activists William "Bill" Yates, a Cornell Utiversity English professor,<br />

and Mike Weaver.'- `<br />

After completing her training Patterson was dispatched to Jonesboro in the<br />

Spring of 1964, joining Danny Mitchell, a Syracuse University graduate student .<br />

Eventually the Jonesboro Summer Project contingent comprised half a dozen activists ;<br />

four blacks and two whites . Fear in the black community was so acute in Jonesboro that<br />

no local black family offered to house the CORE activists . The task <strong>for</strong>ce workers had to<br />

settle <strong>for</strong> a small house on Cedar Street in the black community, lent to them by a<br />

sympathetic black woman who had moved to Cali<strong>for</strong>nia . The CORE workers christened<br />

the small home "<strong>Freedom</strong> House" and set about organizing voter registration .<br />

2°Catherine Patterson Mitchell, interview by author, 6 June 1993, Asheville, North<br />

Carolina, tape recording .<br />

1~

The young activists took seriously their Gandhian belief that their enemies could<br />

be converted by the moral strength of nonviolence, and, accordingly, they began<br />

earnestly searching <strong>for</strong> sympathetic white supporters among town locals . It was a short<br />

search . Virtually all the town's leaders were segregationists, including Sheriff Newt T .<br />

Loe (a "rabid segregationist" noted Danny Mitchell) and Police Chief Adrian Peevy.<br />

CORE discovered only one sympathetic white person, the town pharmacist, and this lone<br />

convert moved by "love and suffering" preferred to keep his conscience to himself.'-'-<br />

CORE's belief in the redeemability ofwhite bigots grew from a perilous<br />

political naivete and an astounding lack ofunderstanding about Southern history . There<br />

were reasons <strong>for</strong> CORE's confidence in the pacifist model of social revolution .<br />

Nonviolence appeared to have succeeded in India, one of the first successful anti-colonial<br />

revolutions following World War II . And the wanton violence of World War II had<br />

accomplished little more than the destruction of sixty million human lives .<br />

But Gandhi's success blinded CORE to how difficult it would be to transfer the<br />

strategy to America. Birmingham was not Bombay . There were critical differences<br />

between India's anti-colonial struggle and the black liberation struggle unfolding in the<br />

Deep South . East Indians were the vast majority in their homeland, Far outnumbering<br />

their oppressors who constituted little more than a tiny occupying army. Support <strong>for</strong><br />

colonialism by the British people was waning in the postwar years . In general, British<br />

workers did not believe that their social and economic status depended on the continued<br />

exploitation of Indians. Cold war rhetoric exalting democracy and freedom made it<br />

diffcult <strong>for</strong> the British to use <strong>for</strong>ce to suppress the rebellion Thus, Gandhi had the<br />

2=Mitchell, "White Paper."<br />

16

advantage of engaging a distant enemy who was constrained from using violence by<br />

domestic indifference and international opinion. Nonviolence succeeded in India only<br />

because the British tacked the resolve to use violence .<br />

The United States was a different matter. In contrast to East Indians, blacks<br />

were a tiny minority surrounded by a white majority . And unlike the British working<br />

class, white Southerners were invested in domination . Slavery protected whites from the<br />

harshest work and provided them with economic security, status and privilege . The<br />

"peculiar institution" had trans<strong>for</strong>med poor whites into gendarmes <strong>for</strong> white supremacy .<br />

Time and again whites demonstrated that they were willing and eager to defend their<br />

caste position at the expense of black life and freedom . Moreover, the geographic<br />

proximity of the whites facilitated their use ofterror as a political tool . And use it they<br />

did . Emancipation made little difference. Whites resorted to wholesale violence to<br />

overthrow the biracial Reconstruction governments . In the years of dejure segregation<br />

that followed, white social and economic status continued to be predicated on black<br />

subjugation . Whites consciously benefited from a system that provided cheap black labor<br />

and exempted them from dangerous and demeaning work. The benefits of segregation<br />

constantly rein<strong>for</strong>ced white loyalty to racism and violence ; and while international<br />

opinion may have influenced the British peerage, it meant nothing to planters in the<br />

Mississippi delta, let alone "corn and 'tater" whites in the piney woods .<br />

It was these underlying material and social intere~~ts that made segregation<br />

impervious to moral appeal . Few in the United Kingdom believed that Indian<br />

Independence betokened the end ofBritish economic security or culture . But southern<br />

society rested on white supremacy. The death of segregation meant the death ofthe old

social order. Segregationists were not far from the truth when they charged that<br />

integration was revolution. The new abolitionists were asking Southern whites <strong>for</strong> more<br />

than their hearts and minds : they were demanding their caste status and the privileges<br />

pertaining thereto . Little mystery, then, that nonviolence failed to evoke love and<br />

compassion in white hearts .<br />

Gandhi had confronted a distant and demoralized enemy constrained by<br />

national and international opinion . African-Americans, in contrast, faced an omnipresent 'i<br />

enemy, willing--if not eager--to use legal and vigilante violence. White racial identity<br />

depended on continued domination and violence, and, as events demonstrated, it would<br />

surrender to nothing less than violence. But the idealistic young CORE activists making<br />

their way into Jonesboro were not to be deterred by history or realpoGtik.~<br />

The reality ofviolence, however, soon became a concern <strong>for</strong> the CORE task<br />

<strong>for</strong>ce . Police harassment had always been troublesome <strong>for</strong> civil rights activists in the<br />

South, and the Jonesboro police did occasionally tail activists during their voter<br />

registration visits in the countryside . But by Southern standards, Jonesboro's police<br />

department treated CORE reasonably well . Danny Mitchell described the police chiefs<br />

policy toward CORE as, "I' m here to protect you . . . but we don't want any<br />

demonstrations ." 2`<br />

'~In this respect, the black liberation movement more closely resembled the<br />

Moslem experience in India. Like their black counterparts in the U.S ., Moslems were a<br />

despised minority violently subjugated by a numerically superior oppressor . It is<br />

noteworthy that the Islamic movement's strategy ofviolence in India resulted in political<br />

independence and self-determination, in the <strong>for</strong>m of Pakistan. For a comparative study of<br />

nonviolence in two countries, see George M. Fredrickson, Black Liberation: A<br />

Comparative History ofBlack Ideologies in the United States and South Africa, (New<br />

York: Ox<strong>for</strong>d University Press, 1995) especially pages 225-276 .<br />

='Mitchell, "White Paper."<br />

l8

A graver danger was posed by Klan and other racist vigilantes . From the outset,<br />

the <strong>Freedom</strong> House was the target of menacing carloads of young whites cruising through<br />

the black community, shouting obscenities and threats. This type of harassment was not<br />

new . For years, whites, acting with impunity, would drive through the black "quarters"<br />

verbally harassing and physically assaulting black residents. The practice, referred to as<br />

"nigger knocking," was a time-honored tradition among whites in the rural South . But<br />

the presence of black and white civil rights activists in the commutity added a frenzied<br />

intensity to the ritual . It was not long be<strong>for</strong>e verbal assaults turned to violence . In one<br />

<strong>for</strong>eboding incident a gang ofyoung whites broke several windows at the <strong>Freedom</strong><br />

House . The black community responded to the attacks with a mix ofconcern and<br />

uncertainty . They had never been confronted with the challenge ofdefending strangers in<br />

their midst . Caution was the order of the day . A reckless display ofarmed self-defense<br />

might provoke whites to retaliate with deadly <strong>for</strong>ce.<br />

The unwritten racial code of conduct in the South <strong>for</strong>bade blacks from using<br />

weapons <strong>for</strong> self-defense against white assaults. Whites reasoned that defensive weapons<br />

had offensive potential . The code also proscribed collective <strong>for</strong>ms of self-defense, a<br />

prohibition no doubt stemming from ancient fears ofbloody slave rebellions .<br />

The black community in Jonesboro anxiously searched <strong>for</strong> a method of<br />

defending their charges without violating the racial code of conduct, but the imntinent<br />

threat ofviolence left few alternatives . Within a few days, a small number of local black<br />

men began to quietly guard the CORE activists in their daily activities . Slowly they<br />

appeared, unarmed sentinels, silent and watchful . At first they did nothing more than sit<br />

19

on the porch of the <strong>Freedom</strong> House, or follow the activists like quiet shadows as they<br />

went about their organizing work . 2s<br />

Among this initial group ofguards was Earnest Thomas, a short, powerfully<br />

built twenty-nine-year-old black man who supported his five children as a papermill<br />

worker, mason, handyman and bar room gambler. Thomas' life centered on the<br />

institutions and amusements of small-town African-American life : he was an occasional<br />

churchgoer, a member of the Scottish Rite Masons, and a barroom hustler . Held at arms<br />

length by the "respectable" black middle class, Thomas nonetheless commanded<br />

community respect <strong>for</strong> his courage and martial skills. His street savvy and cool,<br />

intimidating demeanor earned him the nickname Chilly Willy . "Chilly was very firm,"<br />

recalls Annie Purnell Johnson, a local CORE volunteer . "He didn't care . Whatever he<br />

said he was going to do, he did it ." His determination was accented by his penchant <strong>for</strong><br />

<strong>for</strong>ce. "He was violent too," says Johnson . "He could be very violent if he wanted to be .<br />

Ifyou pushed his button, he would deliver.' °26<br />

Thomas had been a fighter all his life . It was a lesson he learned early in life .<br />

Racial segregation fought a relentless battle against human nature--against the instinctual<br />

longing <strong>for</strong> companionship and shared joy among members of the human race .<br />

Frequently the intimacy of everyday life tempted people to disregard the awkward ritual<br />

of segregation . In his youth, Thomas had frequented the local swimming hole in<br />

Jonesboro, a gentle creek that wound its way through the pines . Its tranquil waters<br />

ZSCatherine Patterson Mitchell, <strong>Hill</strong> interview .<br />

26Earnest Thomas, interview by author, 6, 20 February 1993, San Mateo,<br />

Cali<strong>for</strong>nia, tape recording ; Annie Purnell Johnson, interview by author, 15 November<br />

1993, Jonesboro, Louisiana, tape recording .<br />

20

welcomed children of all colors. Here black and white children innocently played<br />

together, splashing and dunking. At a distance, colors disappeared into a shadow<br />

silhouette ofbobbing heads, the languid summer air disturbed only by occasional shrieks<br />

ofjoy .<br />

Yet, inevitably nature surrendered to the mean habits ofadult society. Thomas<br />

recalls that sometimes the whites would band together and swoop down on a handful of<br />

frolicking blacks, claiming the waters as the spoils of war. On other occasions, Thomas<br />

would join a charging army of whooping black warriors as they descended on the stream,<br />

scattering a gaggle of unsuspecting white boys . The swimming-hole wars of his youth<br />

provided Earnest Thomas with one enduring lesson : rights were secured by <strong>for</strong>ce more<br />

often than moral suasion .<br />

Thomas attended high-school in Jonesboro through the 11th grade then dropped<br />

out and served a stint in the Air <strong>for</strong>ce during the Korean War. Like many young blacks<br />

in the South, military service dramatically changed his attitude toward Jim Crow . Three<br />

years and eight months as an airborne radio operator had af<strong>for</strong>ded him brief and<br />

seductive glimpses ofa world free ofsegregation . He met Northern blacks who, with<br />

better education and more opportunities, were increasingly impatient with the slow pace<br />

ofchange. Thomas absorbed their restless craving <strong>for</strong> freedom . The military also<br />

provided him, and thousands ofother southern blacks, with the tools to realize this dream<br />

of freedom : leadership skills and an appreciation ofthe power of disciplined collective<br />

action . Discharged from the service, Thomas spurned the South and journeyed<br />

Northward to Chicago . He worked <strong>for</strong> one year at International Harvester, but soon<br />

returned to Jonesboro to raise a family.<br />

21<br />

i

Thomas was eager to work with CORE, but he had serious reservations about<br />

the nonviolent terms imposed by the young activists . He admired their devotion and<br />

energy, but the college students seemed dangerously deluded about the potential <strong>for</strong><br />

terrorist violence . And CORE made it clear to Thomas that they were unwilling to<br />

compromise their stand on nonviolence .<br />

If the CORE activists sounded like missionaries, there was a good reason .<br />

CORE was permeated with a religious style of organizing, characterized by an<br />

evangelical faith in doctrine and an unswerving belief in a bipolar world ofgood and evil .<br />

For the young CORE activists, nonviolence was more religion than strategy . And<br />

religious doctrine, as immutable truth, could not be compromised to suit the sinner. One<br />

either accepted or rejected the divinely inspired word . One was either saint or sinner.<br />

Rather than negotiate a strategy with the black community, CORE's support was<br />

contingent on local people accepting the nonviolent creed . The creed could never fail the<br />

people; only the people could fail the creed . Faith was a pillar of CORE's organizing<br />

strategy . The idea that Klansmen could be converted contradicted all reason and<br />

experience and required an act offaith comparable to a belief in the divinity ofJesus . If<br />

black men resisted these nonviolent teachings, it was no cause to reconsider doctrine .<br />

Indeed, the resistance ofthe damned only confirmed the fallen state of mankind and the<br />

urgency ofa new dispensation--one that would appear as enigmatic and paradoxical to<br />

mere mortals as did the teachings ofChrist in his own time. Failure was a sure sign of<br />

success. 2'<br />

2'This uncompromising stance, in some measure, derived from nonviolence's<br />

categorical religious roots . Gandhi had cloaked his strategy in religious garb, imbuing it<br />

with moral authority that resonated with Judeo-Christian beliefs . CORE activists'

But like most black men in the South, Earnest Thomas thought it better to be<br />

damned than dead . He and the other men in the defense group politely resisted CORE's<br />

attempt to dictate the terms ofthe local movement .<br />

Thomas quickly emerged as the leader of the defense group . No doubt his<br />

military training had accustomed him to organization . While other men would come and<br />

go, Thomas made it his responsibility to elevate the level o<strong>for</strong>ganization and instill<br />

discipline and order. During the day, the guards simply watched and kept their weapons<br />

concealed . But the night was different . The veil of darkness provided cover <strong>for</strong> hooded<br />

terrors . The guards knew that a show ofweapons would discourage Klan violence . So<br />

the night brought the moon, the stars, and the guns .<br />

The guns posed a dilemma <strong>for</strong> CORE from the very beginning . The defense<br />

group had no difficulty in accepting CORE's right to determine its own nonviolent<br />

strategy, and on the whole, they thought it an effective one . But they were not prepared<br />

to abdicate their responsibility to defend their community . They were not willing to<br />

religious training predisposed them to believe that a single act could corrupt the spirit;<br />

that violence had corrupted society as original sin had corrupted man . The absolute,<br />

uncompromising nature of nonviolent creed corresponded to the Old Testament doctrine<br />

ofthe Covenant between the Jews and God . According to the Covenant, the Israelites<br />

were protected as long as they con<strong>for</strong>med to God's word . Ifthe Chosen People broke the<br />

covenant, a wrathful God exacted his punishment . Salvation was won on terms of<br />

repentance and subnussion to the law.<br />

Gandhi's concept of Satygraha, suffering that redeems as it converts the enemy,<br />

also closely resembled the Christian concept ofsalvation on terms ofrepentance.<br />

Repentance required suffering, and conscious suffering, submitting to an assailant's<br />

violence, was a sign ofGod's grace . Nonviolence saved the devout as well as the<br />

heathen . On nonviolence, Christian doctrine, and religious symbolism, see Keith D .<br />

Miller, I~oice ofDeliverance : The Language ofMartin Lather King, Jr. and its Sources,<br />

(New York : The Free Press, 1992) and Richard Lentz, Symbols, the News Magc~ines,<br />

and Martin L:~ther King, (Baton Rouge : Louisiana State Jniversity Press, 1990) .<br />

23

extend nonviolence to all aspects of the black freedom movement, particularly in the<br />

center of a Klan stronghold . That would be suicide . They were outnumbered two-to-one<br />

and the police offered no protection .<br />

Underlying the conflict over nonviolence was a deeper issue ofautonomy . Who<br />

would determine the local organizing strategy <strong>for</strong> the black movement? National<br />

organizations, with their imported strategy, dominated by a coalition of middle class<br />

blacks, organized labor, and white pacifists and liberals? Or the local community with<br />

their own strategy determined by local experience?<br />

CORE initially won the philosophical argument, overcoming locals with their<br />

superior debating skills and the <strong>for</strong>ce ofa coherent world view and strategy . Thomas and<br />

other grassroots leaders were less articulate and lacked the clear world view of their<br />

middle class saviors . But slowly "Chilly Willy" and his working class colleagues began<br />

to find words <strong>for</strong> their thoughts and gain confidence in their own judgement and<br />

opinions .<br />

Thomas' quest <strong>for</strong> autonomy was not self-conscious and deliberate . But<br />

instinctively he and the defense group began to assert their authority over local matters .<br />

They wanted the right to defend their community with <strong>for</strong>ce ifnecessary . CORE balked<br />

at these terms and suggested a compromise in which the guards would conceal their<br />

weapons during the day. The debate found its way into many late-night discussions<br />

around the kitchen table in the <strong>Freedom</strong> House. Cathy Patterson recalls the activists<br />

admonishing Thomas : "Chilly, ifyou guys are going to be out there with guns, you have<br />

to hide them ." And Thomas would ask why . "Because you're going to invoke violence,"<br />

replied the activists . "Ifyou have a gun, you have to be prepared to use it . And we don't<br />

24

want people to get hurt ." Patterson recalls Thomas patiently listening to their arguments,<br />

and then answering fu-mly, "You're stepping on my toes . We're doing this . We know<br />

this town . We know these people. Just let us do it ." 28<br />

CORE relented . "What happened was that Chilly Willy and them started going<br />

out with us," recalls Ronnie Moore, and their position was, "O.K., you guys can be<br />

nonviolent if you want to . . . and we appreciate you being nonviolent . But we are not<br />

going to stand by and let these guys kill you ."~'<br />

The defense group's objection to the nonviolent code went beyond the issue of<br />

guard duty. Many of the men, including Thomas, declined to participate in any<br />

nonviolent direct action, including pickets and marches because ofthe rules of<br />

engagement set by CORE . "Ifyou were attacked, ifyou were spat upon, if you were<br />

kicked or jeered, we were very clear that we were not to respond to that," recalls<br />

Patterson . CORE quickly discovered that the black men ofJonesboro were unwilling to<br />

endure the humiliation attending these restrictions . "There was too much pride to do<br />

that," says Patterson. Nonviolence required black men to passively endure humiliation<br />

and physical abuse--a bitter elixir <strong>for</strong> a group struggling to overcome servility and<br />

passivity . Paradoxically, nonviolence compelled black men to sacriSce their manhood<br />

and dignity in order to acquire it .~°<br />

Nonviolence also demanded that black men <strong>for</strong>ego their right to defend their<br />

families . This, too, tested the limits of <strong>for</strong>bearance . The institution of white supremacy<br />

Catherine Patterson Mitcheq, <strong>Hill</strong> interview .<br />

2'Ronnie M. Moore, interview by author, 26 February 1993, New Orleans, tape<br />

recording .<br />

s°Ibid ; Thomas, <strong>Hill</strong> interview .<br />

25

was a complex web of social and political customs, proscribed behaviors, government<br />

policies and taws Some aspects ofracism were more endurable than others . At its most<br />

innocuous, segregation was little more than demeating symbolism . For the most part,<br />

blacks and whites drank the same water, ate the same foods and rode the same busses .<br />

But some racist practices were intolerable insults to black manhood .<br />

Compromising the sanctity of family was one ofthose transgressions. "The<br />

things that go with racial segregation . . . you lived with that," says Cathy Patterson of<br />

separate seating and other peculiarities of physical segregation . "They were things you<br />

just had to accept ." But violence against family and home violated the ancient right to a<br />

safe hearth and home . "When they saw their own children get hit or beaten," recalls<br />

Patterson, the men "reacted very differently." Nonviolence obliged black men to stand<br />

idly by as their children and wives were mercilessly beaten, a debasement that most black<br />

men would not tolerate . They clung tenaciously to their fragile claims to manhood and<br />

honor . It should have surprise no one that nonviolence ultimately discouraged black men<br />

from participating in the civil rights movement in the South, turning it into a movement<br />

ofwomen and children. Black men, unlike their crusading saviors, understood that there<br />

was no equality without honor.<br />

CORE began to slowly grasp the dilemma they had created <strong>for</strong> black men. The<br />

compromise with armed self-defense provoked "intense philosophical discussion and<br />

debates" within the CORE summer task <strong>for</strong>ce in Jonesboro . The controversy eventually<br />

led some activists, like Mike Lesser, to leave CORE . But <strong>for</strong> most activists, the palpable<br />

fear in Jonesboro was gradually eroding their faith in the grand intellectual theories .<br />

There was a conflict over the issue of nonviolence, says Patterson, but "there also was<br />

?6

enough fear that the conflict was more intellectual than it was real ." Patterson herself<br />

arrived at what she considered a principled compromise . "During the day I thought it<br />

was inappropriate to have anyone with us bearing weapons," says Patterson . "But when<br />

it got dark, we were in a great deal ofdanger. I had no objections to their presence at<br />

night . We were defenseless at night ."3 `<br />

Self-defense became an immediate concern as the movement shifted from voter<br />

registration to direct action anti-segregation demonstrations . CORE's initial voter-<br />

registration drive provoked some harassment--generally limited to white teenagers<br />

driving through the community, shouting taunts . Most whites regarded CORE's presence<br />

as a nuisance more than a dangerous menace . Voter registration organizing confined<br />

CORE activists to the black community, so the organizers seldom crossed paths with<br />

local whites . The subdued response by whites was understandable. Despite its<br />

symbolism, black voter registration posed little threat to white supremacy and the<br />

segregated caste system . Even if all blacks in Jonesboro were registered, they would<br />

comprise only one-third of the vote . At best, the black vote could be bartered <strong>for</strong><br />

influence, but it would not fundamentally alter social relationships. White businesses<br />

would continue to thrive on segregated labor, white jobs would remain secure, and life<br />

would amble along as usual in the little mill town .<br />

But desegregation was another matter . Segregation was the foundation ofthe<br />

social and labor systems ofthe South . Whites understood that desegregation challenged<br />

the system of privilege that ensured them the best jobs, housing; education and<br />

government services. If the segregation barriers fell, white workers lost substantially<br />

3`Catherine Patterson Mitchell, <strong>Hill</strong> interview .<br />

27

more than a separate toilet . The conflict over segregation was ultimately a deadly contest<br />

<strong>for</strong> power--as Jonesboro blacks were soon to discover .<br />

?8

Chapter 2<br />

The Art of Self-Defense<br />

At the beginning ofJune 1964, the CORE task <strong>for</strong>ce in Jonesboro began to plan<br />

<strong>for</strong> direct action desegregation protests to test the new civil rights bill which would<br />

become effective in July. The prospect of a militant desegregation campaign similar to<br />

Birmingham provoked considerable anxiety in the black community . Many blacks feared<br />

that Jonesboro's tiny six-man police department would prove unwilling or incapable of<br />

protecting the activists . And it was increasingly clear that Earnest Thomas' in<strong>for</strong>mal<br />

defense group was an insufficient substitute <strong>for</strong> police protection.<br />

Taking the initiative to avert a disaster was a newcomer to the black community,<br />

Frederick Douglas Kirkpatrick . At six-feet-four-inches, Kirkpatrick was an imposing<br />

figure . A stern visage and stentorian basso voice gave him a commanding presence and<br />

natural leadership qualities . Kirkpatrick arrived in Jonesboro in 1963, an ambitious<br />

young high school athletics coach from nearby Homer in Claiborne Parish . In Homer,<br />

Kirkpatrick had led his teams to two state championships . Now he had advanced his<br />

career as the new physical education teacher and athletics coach at Jackson Parish High<br />

School, the black high school in Jonesboro . Though he had no <strong>for</strong>mal religious training,<br />

Kirkpatrick had assumed the title ofReverend, a common practice in his day .<br />

Kirkpatrick's father had provided him with a religious upbringing, and the elder

Kirkpatrick himself was a Church ofGod in Christ sanctified preacher who had built an<br />

impressive ministry of three churches in Claiborne Parish .`<br />

ICirkpatrick's optimism about his new position quickly gave way to<br />

disappointment . The conditions at Jackson Parish High School were abominable .<br />

Jackson F~Lgh offered no <strong>for</strong>eign languages . A new library was tilled with empty shelves .<br />

Textbooks were tattered hand-me-downs from the white schools. Students were<br />

routinely dispatched as gardeners to maintain the Superintendent's personal lawn . The<br />

only vocational offerings were home economics and agriculture, a curriculum that<br />

condemned blacks to lives as maids and sharecroppers . It was these conditions and the<br />

threat ofKlan violence that motivated Kirkpatrick to become active in the local civil<br />

rights movement . 2<br />

Kirkpatrick and a group offellow black leaders began discussing the idea ofa<br />

black volunteer auxiliary police squad that would assist police in monitoring Klan<br />

harassment in the black community . Unlike Thomas' in<strong>for</strong>mal self-defense group, the<br />

auxiliary police utit would be oi~cially sanctioned, providing legitimacy and respect . It<br />

was a bold yet fiscally attractive proposal . The city would enjoy added police protection<br />

at no additional expense during the desegregation tests .<br />

Kirkpatrick approached Chiefof Police Peevy with a <strong>for</strong>mal request <strong>for</strong> a special<br />

volunteer black police squad to patrol the black community . Much to their surprise,<br />

ChiefPeevy accepted the proposal and promptly deputized Kirkpatrick and several other<br />

blacks, including Henry Amos, Percy Lee Brad<strong>for</strong>d, Ceola Quals and Eland Hams .<br />

'Kirkpatrick, HaU interview .<br />

=Ibid .<br />

~o

Peevy issued the squad an old police car with radio, guns, clubs and handcuffs,<br />

and local white merchants donated money to outfit the squad in crisp new uni<strong>for</strong>ms . The<br />

Police Chief assured them that their police powers extended to whites as well as blacks,<br />

and that they could arrest whites ifnecessary . It was a small development, but Jonesboro<br />

had made history by creating the first and only volunteer black police <strong>for</strong>ce in the modern<br />

civil rights movement.'<br />

Chief Peevy's decision to <strong>for</strong>m the squad appeared uncharacteristically<br />

enlightened <strong>for</strong> a white lawman in North Louisiana, and many in the black community<br />

questioned his motives . Some, like Earnest Thomas, suspected that Peevy planned to use<br />

the squad as a convenient and politic way to discipline and control the civil rights<br />

movement : "They were looking <strong>for</strong> some black policeman to do their dirty work," scoffs<br />

Thomas . {<br />

Kirkpatrick understood the dilemma confronting him . He knew that Chief Peevy<br />

expected the black police squad to discourage demonstrations and arrest civil rights<br />

workers . But Kirkpatrick thought that, despite these limitations, the squad could provide<br />

a modicum of protection <strong>for</strong> the black community and CORE .<br />

It was not the only dilemma Kirkpatrick confronted . Though a respected<br />

community leader, Kirkpatrick also occupied jobs that obligated him to the white power<br />

structure . He was employed by the pubic schools as a teacher-coach and also employed<br />

by the city as a part-time manager of the public swimming pool . His position as de facto<br />

;Charles White, interview by author, 11 November, 1993, Jonesboro, Louisiana,<br />

tape recording .<br />

TThomas, <strong>Hill</strong> interview.<br />

3l

chiefof the black police placed him in a potentially compromising position . Local laws<br />

and courts mandated segregation and gave police impunity to disrupt civil rights protests .<br />

In his new role, Kirkpatrick would be thrust in the embarrassing position ofen<strong>for</strong>cing<br />

segregation laws and thwarting lawful protests. Many agreed with Earnest Thomas'<br />

observation that Kirkpatrick was wearing "too many hats." S<br />

Among the members ofthe new police squad were several men who had already<br />

worked with Thomas in the in<strong>for</strong>mal defense group . They were mature and respected<br />

community leaders, like Brad<strong>for</strong>d and Amos, who had been active in the Voters Leag~~e .<br />

All of the volunteers were relatively independent ofthe white power structure . Amos<br />

owned a gas station, Harris was a barber, and Brad<strong>for</strong>d owned a cab service and also<br />

worked at the mill . The black police squad began patrolling the community at tight in<br />

June 1964, assuming many of the duties ofthe in<strong>for</strong>mal defense group . The patrol<br />

appeared to deter harassment, and aside from a few incidents, June was relatively quiet .<br />

At the beginning ofthe Summer, Cathy Patterson and Danny Nfitchell were joined<br />

by two more black CORE task <strong>for</strong>ce organizers, Fred Brooks, a black college student<br />

from Tennessee, and Willie Mellion, a young black recruit from Plaquemine, Louisiana .<br />

The expanded task <strong>for</strong>ce continued its work with the Voters League, concentrating on<br />

voter registration. But the implementation ofthe Civil Rights Act's public<br />

accommodations provisions in July 1965 radically changed the strategy ofthe civil rights<br />

movement . Previously CORE's summer project had centered on voter registration,<br />

which liberal contributors and foundations had supported financially. Liberals viewed<br />

SIbid .

the vote as key to trans<strong>for</strong>ming the South and also hoped that new black voters would<br />

strengthen the Democratic Party in the upcoming Fall presidential race . 6<br />

But <strong>for</strong> most blacks in Jonesboro, voter registration was more symbolism than<br />

substance . As July drew nigh, young people in particular grew increasingly impatient<br />

with the racial barriers to education, public accommodations and employment . They<br />

importuned the CORE activists with demands <strong>for</strong> direct action protest to test the public<br />

accommodations provisions of the Act.<br />

Local people were not the only impatient ones . On June 22, Fred Brooks, the<br />

irrepressible and buoyant young CORE organizer from Tennessee, boldly flaunted<br />

segregation laws by drinking from the "whites only" water fountain in the Jackson Parish<br />

Court House . Deputy W . D . McBride hustled Brooks into the Sheriff Loe's office and<br />

ordered him not to repeat the offense . Brooks spun on his heels, headed toward the<br />

fountain and defiantly drank from it again .'<br />

Deputy McBride, flustered and seething, ordered Brooks back into his office and<br />

hastily summoned Kirkpatrick in his capacity as a police deputy. It was the first test of<br />

the black police. When Kirkpatrick arrived, a furious Sheriff Loe cornered Kirkpatrick .<br />

"You'd better tell this boy something about drinking from these white water fountains,"<br />

DDanny 1Viitchell, "VEP Field Report," 24 June 1964, 124-770, Congress of Racial<br />

Equality (CORE) Papers, microfilm, ARC .<br />

'Danny Mitchell, "A Special Report on Jonesboro, Louisiana," July 1964, box 1,<br />

folder 10, Jackson Parish Files, CORE Papers, SHSW [hereinafter cited as<br />

CORE(Jackson Parish)] .

steamed the Sheriff "I'm not gonna have this . I'm gonna peel his damn head ." The<br />

incident ended without an arrest . $<br />

Relations with taw en<strong>for</strong>cement continued to deteriorate as CORE stepped up its<br />

desegregation protests . On July 4, a sheriffs deputy detained Robert Weaver, a CORE<br />

task <strong>for</strong>ce worker, and took him to the police station <strong>for</strong> interrogation and finger printing .<br />

Sheriff Loe lectured Weaver that blacks did not need CORE since they could register to<br />

vote in Jackson Parish . Loe warned Weaver to leave town by morning and one deputy<br />

threatened to "bust his head" if he saw Weaver again .'<br />

Bonnie Moore and Mike Lesser became the next victims ofthe terror campaign.<br />

On July 8 the two organizers left Jonesboro <strong>for</strong> the short one hour drive to Monroe. As<br />

they left town, they noticed three carloads of whites abruptly pull onto the highway<br />

behind them . Lesser nervously watched in the rear view mirror as the cars trailed behind .<br />

He and Moore were seasoned activists who understood the danger posed by the stalking<br />

caravan . The two tensely discussed their predicament . With rugged terrain skirting both<br />

sides of the road, the only option was to stay on the blacktop . Lesser pushed the<br />

accelerator in an ef<strong>for</strong>t to outrun the pursuers, but one car in the caravan suddenly passed<br />

them, blocking their escape . Moore and Lesser frantically debated whether to ram one of<br />

the cars from behind . As the seconds ticked away the two continued to speed deeper into<br />

the pine <strong>for</strong>est and further away from the relative security ofJonesboro . Moore decided<br />

aIbid .<br />

'Ibid .<br />

34

that they had to turn around . He ordered Lesser to execute a quick U-turn in the middle<br />

ofthe road . `°<br />

Lesser slanvned the breaks and wheeled the car around, placing their vehicle on a<br />

collision course with the two remaining pursuers who were blocking both lanes . Bonnie<br />

Moore recalls the fatalistic mood . "We decided at that moment that we were going back<br />

to the freedom house, either in one piece or with one of those cars ." Lesser dropped the<br />

accelerator to the floor and streaked toward the oncoming cars . At the last moment one<br />

of the pursuing cars veered to the side and was sideswiped as Lesser and Moore sped by .<br />

"That was the first game of chicken that I probably ever played," remembers Moore."<br />

Lesser and Moore sped back to Jonesboro, reaching speeds of one-hundred nines<br />

an hour . From the safety of the <strong>Freedom</strong> House, they called the sheriff s oi~ce to file a<br />

complaint . Within minutes, Sheriff Loe and members of the black police squad arrived .<br />

Loe had already received a complaint from the whites who Moore and Lesser had eluded .<br />

To their amazement, Loe ordered the black deputy to arrest Lesser and Moore <strong>for</strong><br />

reckless driving and leaving the scene of an accident . The deputy refused and Loe<br />

eventually departed. Fearing another attack on Lesser and Moore, members of the black<br />

squad provided the CORE activists with an armed escort back to Monroe that evening .<br />

SheriffLoe's attempt to have the black deputy arrest Lesser was the first time that the<br />

black police failed to per<strong>for</strong>m according to his expectations . It was clear that the squad<br />

was not going to be wining accomplices in repression .<br />

` °This account taken from Ibid . and Moore, <strong>Hill</strong> interview .<br />

"Ibid .<br />

35

The campaign ofharassment against CORE increased in the days following the<br />

implementation ofthe Civil Rights Act . On July 11, six CORE task <strong>for</strong>ce members<br />

including Brooks, Weaver, Yates and Patterson were stopped by Jackson and Lincoln<br />