Swing and Sensibility

Whatever Frank Sinatra sang, he swung, and his musicianship will endure longer than the swagger that today's singers so admire

When anyone asks did I see Sinatra, I answer yes; I saw him in Philadelphia in November of 1991, on his "Diamond Jubilee" tour. Really, though, all I saw from my seat in the press box was a tuxedoed snowcap who looked a little bit like Casey Stengel and occasionally sounded like him too. I wound up watching Sinatra on a color monitor suspended from a scoreboard, feeling no closer to him than if I were at home, watching him on video. What I most noticed was his hands—translucent, veined, and, to judge from his weak grip on the microphone, arthritic.

Almost forty years before, on his first collaboration with the arranger Nelson Riddle, in 1953, when Sinatra sang of having the world on a string, he might as well have had it dangling. He spent the next fifteen or so years taking songs off the market. Who wanted to hear anyone else do "Angel Eyes" or "I've Got You Under My Skin"? His interpretations were immediately accepted as definitive. During these years, with assistance from Riddle, Gordon Jenkins, and Billy May, among other arrangers, Sinatra originated what is generally called the concept album, though in his case I prefer to think of it as the LP of sensibility. Many performers, including Sinatra, had released collections of songs that were related in some way as far back as the 1940s, before the long-playing album was even invented. Sinatra's innovation, on a series of albums initiated by Songs for Young Lovers, in 1953, was to make a concept out of mood. Unlike Ella Fitzgerald (whose albums for Verve in the late 1950s combined with Sinatra's for Capitol to define an adult market for pop standards at a time when teenagers were beginning to dominate the singles charts), Sinatra never recorded composer songbooks. He didn't share billing. The unifying theme of his classic albums was either that he was feeling dreamy and sad (as on In the Wee Small Hours and Only the Lonely) or that he was feeling too marvelous for words (as on Come Dance With Me and Songs for Swingin' Lovers). Eventually he himself became the concept; by 1964, when he recorded Frank Sinatra Sings Days of Wine and Roses, Moon River, and Other Academy Award Winners, the selling point wasn't that all the songs were Oscar winners but that Sinatra had deigned to sing them.

Despite quick fame as the best of the "boy" singers of the early 1940s, and also as the cutest in the eyes of that era's hysterical teenage girls, Sinatra didn't hit his stride as a singer or an actor until the early 1950s, when he was pushing forty and starting to lose his hair. Part of the Sinatra legend is that he was destined for oblivion until he switched labels, from Columbia to Capitol, in 1953. Sinatra wasn't really washed up; he was just no longer a craze. His recording of "Mam'selle," a keepsake from the movie The Razor's Edge that reached the top of Billboard's chart in 1947, would be his last No. 1 single until "Learnin' the Blues," in 1955. But he put a whopping forty-three songs on the Top 40 between "Mam'selle" and the expiration of his Columbia contract, including nine in the Top 10. These were mostly covers of other singers' hits, including Nat King Cole's "Nature Boy" and the Weavers' "Goodnight, Irene," or novelty tunes, such as "One Finger Melody" and "Don't Cry, Joe (Let Her Go, Let Her Go, Let Her Go)," for which Sinatra didn't bother to conceal his contempt. But also among his chart entries in these years were "Almost Like Being in Love," "What'll I Do?," "But Beautiful," "I've Got a Crush on You," and the haunted "I'm a Fool to Want You"—which, legend has it, Sinatra, still licking his wounds after being dumped, completed in one take before fleeing into the night. Sinatra's dip in popularity, his romantic misadventures, his quick temper, and the rumors that began to surface about his mob connections—all the things that supposedly put his career in jeopardy—ultimately worked to his advantage. They shifted his appeal from women to men, giving him credibility as the guy on the next barstool, a singing Bogart, the recipient of an honorary degree from the School of Hard Knocks. At least two generations of American men came to love him not just for his singing but for his having met middle age head on, with a combination of style and swagger they hoped might also do the trick for them. He was them with talent and the privilege it can buy.

F. Scott Fitzgerald to the contrary, American life is swimming with second acts, the longest of them interminable. Artists who die young, in full possession of their gifts, are remembered mostly for dying. Performers who survive to old age—as Sinatra somehow did despite those Camels and sips of Jack Daniel's that were never just bits of stage business—suffer a perhaps greater indignity: they become living reminders of their audience's mortality.

SINATRA was on stage about ninety minutes that night in Philadelphia—a good night's work for anyone. But he spent much of that time resting on a stool while being serenaded with a medley of his greatest hits by the unctuous Steve Lawrence and Eydie Gorme. The most alarming sign of his diminished capacity was the teleprompter Sinatra apparently needed to recall lyrics he'd been singing from the heart for decades.

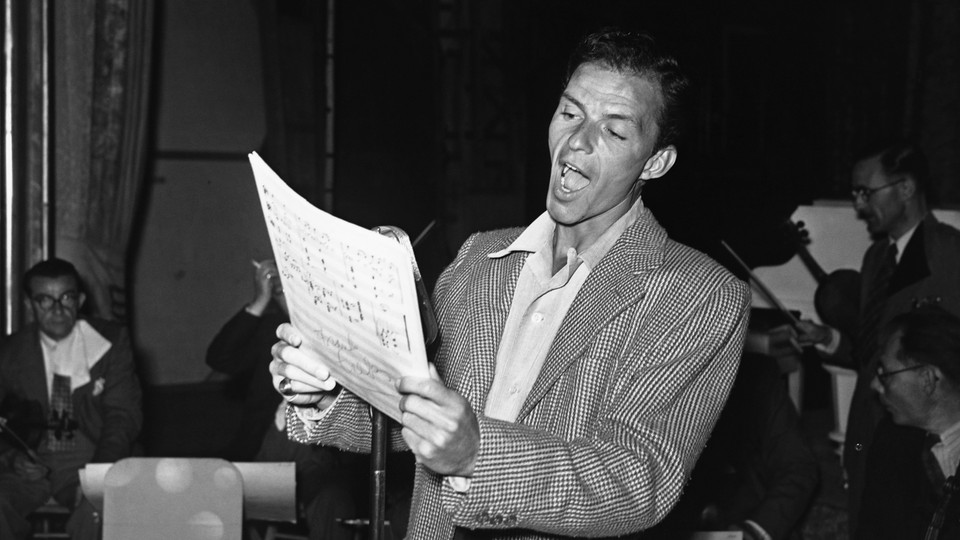

Am I making too much of Sinatra's electronic crib sheet? A friend who saw him on the same tour points out that photographs of Sinatra in the recording studio in the 1950s and 1960s show him looking at scores, even though he was unable to read music. I doubt that this proves that Sinatra never bothered to memorize lyrics. I see it as evidence of his intuitive musicianship, his way of keeping an eye open for dynamic markings and the vertical movement of notes. Regardless of his arranger or conductor, or who was listed as the producer, Sinatra was the arbiter of how the final take should sound. James Van Heusen and Sammy Cahn's "Only the Lonely" is familiar as the title track of a 1958 album that Sinatra often named as one of his favorites. On the three-disc Frank Sinatra / The Capitol Years this art song disguised as a ballad—which Sinatra seems never to have performed in concert, probably because of the difficulty that certain of its intervals would have presented to a road-show orchestra—begins with Sinatra's spoken instructions, and he could be Martin Scorsese telling his cinematographer what he wants in the next shot. "The whole orchestra should be fairly light from the beginning of the vocal," Sinatra says, presumably to Felix Slatkin, the violinist and concertmaster. "From bar eleven ... to the beginning of the crescendo."

One gathers that Sinatra's studio associates followed his orders not because he was a star and a tough guy but because his suggestions invariably worked like a charm (he is said to have given the arranger Gordon Jenkins the idea for the out-of-the-mist solo French horn that precedes the full orchestra on their 1957 recording of Leonard Bernstein's "Lonely Town"). But in 1993, when he began to record the material for Duets and Duets II (albums that proved to be his all-time best sellers, and also his recording swan song), he wasn't even in the studio at the same time as his duet partners, an assemblage of rock and pop glitterati many of whom Sinatra had probably never heard of. He simply laid down his vocals and then (in effect) told his producers to send in the clowns.

The night I saw Sinatra, it took all of his concentration just to get the words right. He seemed never to glance at the prompter, but there were times when he probably should have. On "Luck Be a Lady," instead of asking Lady Luck not to "blow on some other guy's dice" he twice asked her not to "spit."

Sinatra's failing memory, rumored to be a symptom of Alzheimer's and to be compounded by failing eyesight, was hardly the only problem on his final tours. The sheer size of the venues he played (the 18,000-seater in Philadelphia where I saw him was far from the largest) precluded the intimacy he needed to put across his ballads. His claim to be just a glorified saloon singer was a showman's conceit; he was a big-band singer who had outlived his era's ballrooms, movie palaces, and music fairs. As a singer whose pipes gave out on him before his desire to perform did, he would have found his natural habitat in cabaret—if only he could have followed the example of many of the singers he most admired, including Mabel Mercer and Sylvia Syms, and fallen back on his phrasing, limiting his accompaniment to his longtime pianist, Bill Miller. But what room could have accommodated the throngs who wanted to hear him, no matter how many sets a night he pushed himself to perform?

IN his prime, Sinatra wrote the book on phrasing. No other popular singer ever knew better the combined value of precise diction and conversational delivery, and no other has ever been more aware that the beat shouldn't necessarily fall where the rhyme does. (One of a lyricist's jobs is to make the words rhyme; before rap, one of a singer's was to deliver the lyrics in such a way that nobody would notice.) Sinatra may have been an intuitive musician, but he was an analytical singer. He knew that to inflect a word or a syllable that seems not to call for it can shift the rhythm and increase the sincerity of a lyric, by making it more like speech, and can also lavish attention on an especially attractive melodic phrase. If this sounds arcane, just listen to Sinatra sing "Don't change a hair for me" on his 1953 recording of "My Funny Valentine." Most singers stress "change" or "hair," passing up the opportunity to plumb the lowest, most unexpected, and loveliest note in Richard Rodgers's melody. In Sinatra's case the usual stress would also have meant passing up an opportunity to show off his bottom range, which he tended to use sparingly (except when he sang "Ol' Man River") but always to gorgeous effect.

The strings and horns on Sinatra's greatest Capitol and Reprise recordings weren't there for protective coloration, even though some of Sinatra's staunchest champions have questioned his pitch. I side with Henry Pleasants, who argued in The Great American Popular Singers (1974) that because the trombonist Tommy Dorsey and the violinist Jascha Heifetz, both of whom Sinatra frequently cited as influences, played instruments of unfixed pitch, Sinatra emulated their "ambiguity of intonation" along with what he once referred to as the "flowing, unbroken quality" of their phrasing.

A taste for Heifetz would explain Sinatra's flair for portamento—the ease with which he glided from note to note without taking an audible breath. The tips on breath control that he picked up from watching Dorsey enabled the young Sinatra to hold a note practically forever, as we hear him doing to climax "Ol' Man River" in the 1946 film biography of Jerome Kern, Till the Clouds Roll By. I think Pleasants would say that the technique served a greater musical purpose. It allowed Sinatra to deliver lyrics in phrases longer and more irregular than the standard four or eight bars, thus liberating him from the singsongy delivery of most of his generation's white pop singers. And it allowed him while holding a note to move it up or (more often) down the scale without disrupting the melodic flow.

This last trait would also help to explain why Sinatra was drawn to songs liberally spiked with chromatics, including Harold Arlen's "One for My Baby (And One More for the Road)," though Sinatra may initially have responded to the barroom camaraderie in Johnny Mercer's lyrics. The several recordings of this tune that Sinatra made with just Bill Miller on piano (including one from 1993, to close Duets, on which Sinatra exploits his aged vulnerability to great interpretive effect) give a hint of the pleasures he might have offered toward the end of his life had he been able to perform in small rooms.

THE explanation usually given for Sinatra's spotty track record on screen is that he didn't take acting as seriously as he did singing. The way I see it, anyone capable of giving performances as nuanced and watchable as Sinatra's in From Here to Eternity, The Man With the Golden Arm, Some Came Running, and The Manchurian Candidate has nothing to apologize for. Hollywood misused him, first by remaining skeptical of his sex appeal despite the quakes he set off at the Brooklyn Paramount, and later by giving him carte blanche to run wild with the Rat Pack in vanity productions like Robin and the Seven Hoods and Sergeants Three.

My favorites among Sinatra's star vehicles are the ones in which his acting and singing are indivisible. Young at Heart (1954) is one of Sinatra's best pictures, for the same reason that Viva Las Vegas is one of Elvis Presley's: as Ann-Margret was to Presley, Doris Day was to Sinatra—the female co-star who came closest to matching him in screen presence, singing ability, and androgynous erotic force. (Sinatra also has great chemistry in the film with Ethel Barrymore, who plays Day's aunt, with whom he flirts shamelessly.) Young at Heart is a remake of Four Daughters (1938), the movie that made John Garfield a star. Sinatra inherited Garfield's role as a Gloomy Gus songwriter who turns up on the doorstep of a cheery small-town family whose eligible daughters are all in love with another composer—a happier, better-adjusted fellow played by Gig Young.

To make ends meet while he helps Young orchestrate his magnum opus, Sinatra takes a job singing and playing piano in a noisy local pub. In a virtual dramatization of Sinatra's own postwar skid he sings "Someone to Watch Over Me" beautifully —shiveringly—but almost to himself, amid the clatter of dinner dishes and the conversation of people doing a fine job of entertaining themselves. The only one paying any attention is Day, who realizes there's more to him than meets the eye. She's as transfixed by his interpretation of Ira Gershwin's lyric as if it were a mating call.

This was Sinatra's rite of passage as a leading man, in real life as well as in the movies. He may no longer have had bobby-soxers swooning in the aisles, but his turn opposite Day suggested that he was capable of turning grown-up women to mush with the bottomless emotion he conveyed in song. Acting was extra.

A question I heard asked on TV following Sinatra's death was whether he was different in private from the way he was in public. My guess would be that for better or worse, he was no different at all. "Sinatra singing a hymn of loneliness could very well be the real Frank Sinatra," James Van Heusen and Sammy Cahn, who probably knew him better than anyone else, once wrote. Wouldn't it be nice to think so? From the very beginning the tension was between Sinatra's image and the slightly different story told by his voice. His initial appeal to teenage girls of the 1940s was comparable to that of Leonardo DiCaprio to pre-teen girls in our quicker, more jaded day. The young Sinatra came across as a boy who might try to sweet-talk a girl into going all the way but wasn't going to be insistent—unlike the boys his fans knew in real life, most of whom were desperate not to march off to war still virgins. Indulgent parents perceived Sinatra as safe, and so did many of their daughters. Often what young girls want in a boy is another girl, and the girls who swooned over Sinatra pressed him to their hearts as a young man who was as sensitive and, on some level, as self-conscious as they were.

But listen today to Sinatra's recordings with Dorsey and you hear something else—something of which his female fans may have been subliminally aware. You hear a singer whose control of every aspect of his delivery hints at expertise in other areas, including sex. Sinatra's technique and almost literary insight into lyrics gave him greater staying power than any of his rivals singing with big bands. The other quality that separated him from them was the subtlety of his rhythm, which was superior to that of most of the Dorsey band's instrumental soloists and arrangers—even though swinging wasn't necessarily part of a band singer's job description.

IN the late 1960s and the 1970s Sinatra recorded his own interpretations of songs by Stevie Wonder, George Harrison, Paul Simon, and Jim Croce, among others, in a bid to keep himself current. He sounded absurd, and not just because the lyrics held no meaning for him. Whatever its virtues, rock-and-roll doesn't swing, and Sinatra couldn't bring himself not to. Yet neither the implied condescension of these performances nor Sinatra's earlier antipathy toward rock ("the martial music of every sideburned delinquent on the face of the earth," he called it in 1957) has prevented today's middle-aged rockers from claiming him as a father figure, in what one could interpret as an attempt to make peace with their actual fathers.

In presenting Sinatra with a Grammy Legend award in 1994, Bono, of the Irish rock group U2, waxed poetic: "Rock-and-roll people love Frank Sinatra because Frank Sinatra has got what we want—swagger and attitude." But Sinatra singing a ballad could be courtly and compassionate, and much of what Bono and Bruce Springsteen, too, applaud as swagger in his up-tempo performances was actually swing—the je ne sais quoi of jazz but a commodity foreign to most of today's rock and pop.

On an episode of A&E's "Biography" series that was shown a few weeks after Sinatra's death, Camille Paglia said, "Sinatra belongs to a period where men were men and women were women." What seems more important is that he also belonged to the swing era, a period when pop and jazz were more or less the same thing. Sinatra considered himself a jazz singer, and I fear that the fewer Americans there are who know anything about jazz, the harder this aspect of his style is to grasp.

The jazz instrumentalist of whom Sinatra has always reminded me most is the tenor saxophonist Lester Young —perhaps the most innovative soloist to come along in jazz between Louis Armstrong and Charlie Parker. Young first announced his individuality by forgoing the rococo sound projection and big vibrato favored by his day's reigning tenor star, Coleman Hawkins, in favor of a quicksilver tone with almost no vibrato at all. Hawkins was to Young, who in the 1930s used his bottom register only strategically, as Bing Crosby was to Sinatra, who may have been the first pop baritone not to try to make his voice sound deeper. Young's most vital contribution to jazz, however, was the slipperiness of his rhythm— an area in which Sinatra also excelled. Sinatra often swung by postponing or displacing the beat rather than by emphasizing it. On records when we hear Sinatra snapping his fingers, it's usually to acknowledge that he and the beat are a few degrees apart, though destined for a rendezvous.

Young, like many great jazz musicians, adored Sinatra; legend has him sitting in his hotel room across the street from Birdland, alcoholic and near death, playing Sinatra records over and over, perhaps recognizing something of himself in them. Miles Davis also loved Sinatra, and his LP collaborations with the arranger Gil Evans, beginning with Miles Ahead (1957), may have been inspired by Sinatra's with Riddle (like Evans, Riddle was a genius at isolating fragments of melody and highlighting specific instruments, especially woodwinds). One of Sinatra and Riddle's models, I think, was the great Count Basie Orchestra of the mid-1950s—a powerhouse noted for its biting brass. References to Basie, both musical and lyrical, abound on Sinatra's Capitol recordings (on "Come Dance With Me," for example, Sinatra sings, "Hey there, Cutes, put on your Basie boots"), and it seems like more than coincidence that the two men experienced career renewals at around the same time. One of my unsubstantiated Sinatra fantasies is that his chief goal in forming his own label in 1960 was to sign Basie and be able to record with him whenever he desired.

A few nights after Sinatra's death Nick at Nite rebroadcast a grainy black-and-white film of a 1965 St. Louis benefit concert featuring Sinatra and Basie on the same bill as Dean Martin and Sammy Davis Jr. The show was promoted as a Rat Pack spectacular, and nobody who tuned in hoping to see the three singers getting juiced together and cracking wise about it would have been disappointed. But Sinatra is all business during his own up-tempo set with Basie, even while being heckled from the wings by Davis and Martin, both of whom are armed with hand mikes. Martin attempts to throw off Sinatra's timing by singing along with him on "Please Be Kind." At one point Martin, after correctly observing a rest, moos the title phrase dead on the beat, a split second ahead of Sinatra. "You got a beat like a cop," Sinatra deadpans, while the Basie band soars behind him. And it's true: compared with Sinatra, most pop singers of his day were flatfoots.

THROUGH middle age Sinatra was inimitable. Not so the blustering old man who, already a self-parody, gave impressionists such as Joe Piscopo and the late Phil Hartman such a broad target—the Sinatra whose anthem became "My Way," a tuneless bolero of self-seduction, less a song than an epitaph inscribed on a tombstone that he dragged onstage with him toward the end.

This Sinatra was the one I saw most often on television in the hours after he died, and before the weekend was over, I wanted to grab a shovel and bury him myself. I hope this doesn't sound as if I resented Sinatra for getting old, or for not calling it quits when he should have. It's just that I fear this is the only Sinatra younger people know, and therefore the Sinatra who will live the longest in our national memory. I don't want to remember him singing "My Way," a lyric that spoke to something crude and self-delusional in contemporary American life and in Sinatra himself. It's practically a musicalization of Las Vegas, the alternative universe that Sinatra created for himself in the desert when rock-and-roll proved not to be a passing craze. I prefer the Sinatra who sang any number of hymns to romantic love that were as absolute as a Christian prayer, beginning (when I think about it) with his 1939 recording of "All or Nothing at All" with Harry James. Even more I prefer the Sinatra I saw with Count Basie on Nick at Nite. That Sinatra was irresistible, not just for his singing but for the cocksure way he moved his shoulders in time with the rhythm section and even for the way he looked in what I have come to think of as his Yves Montand period—fifty years old and no longer pretty, but the perfect image of a uniquely American type, the swinger existentialist, right down to the cigarette and booze and the slight indentation in his right cheek (said to be from the forceps that were used to deliver him) that made him ruggedly handsome as his face started to crease.

In 1965, the same year that Sinatra and Basie did the St. Louis benefit concert that was rebroadcast on Nick at Nite, the two also performed together at the Newport Jazz Festival. Among those in attendance in a crowd of perhaps 15,000 was the photographer Burt Goldblatt, who years later wrote about the event in his book Newport Jazz Festival:The Illustrated History. Sinatra left the stage by helicopter, already airborne as the applause for him crescendoed.

The audience responded with a genuine outpouring of warmth in return. His impeccable phrasing, his way with a lyric -- that night he had it all -- and if he had had the greatest public-relations firm working out a dramatic departure, they couldn't have come up with a more effective answer than that slowly ascending helicopter blinking its lights good-bye. When the crowd finally drifted off, something seemed to be missing that night. I think it was the opportunity to tell him in person how great he had sounded to us all.

I wasn't there to see it, but this is the Sinatra I want to remember.

Francis Davis is a contributing editor of The Atlantic.

The Atlantic Monthly; September 1998; Swing and Sensibility; Volume 282, No.3; pages 120 - 126.