Musicology is the practice of musical genealogy. Much like digging into one’s own ancestry, the process works backwards. You start with a song or a band and then trace its roots as far back as you can.

When I like a song, I can’t help but probe into its DNA. Who wrote it, what is the name of the band, how many people are in it, have they been in any other bands I might know, how long have they been around, how many records have they put out, where are they from, who are their influences, and if they are still playing, where and when can I go see them?

The internet has made musicology infinitely easier than it was before information became available at the click of a button. These days, if I hear a song I like, I whip out my phone and use the Shazam app. Shazam will tell me the name of the song, the name of the artist and the name of the record. Then I can go to Google and instantly find every answer to the questions above.

When I first got interested in musicology, it was way more difficult. And like so many things related to music, it was the Grateful Dead that sparked my interest in looking backwards into the roots of songs.

The Grateful Dead melded rock ’n’ roll, blues, folk, bluegrass, country and jazz into their music. And I wanted to know from which traditions their songs came.

Here is a classic example: The Grateful Dead played a song called “Wang Dang Doodle.” I had a record called “The London Howlin’ Wolf Sessions” with “Wang Dang Doodle” on it. Looking at the credit below the song title on the record, the songwriter was identified as Willie Dixon. Some research into Willie Dixon revealed that he also wrote “Spoonful” and “Little Red Rooster,” songs that the Grateful Dead also played. More research led to the discovery that The Rolling Stones, Cream, Jeff Beck, The Doors and Led Zeppelin recorded Dixon’s tunes. That was enough for me to go buy my first Willie Dixon record, “I am the Blues.”

The best source of information about the blues in those days came from Robert Palmer’s book “Deep Blues,” which basically traced all rock ’n’ roll and blues back to Robert Johnson.

This brings me to a song in the Grateful Dead repertoire that gave me fits for 25 years. One of my favorite Grateful Dead songs was one with which they opened many of their shows, a song called “Let the Good Times Roll.” Its opening lyrics go: “Get in the groove and let the good times roll, we gonna stay here ‘till we soothe our soul, if it takes all night long.”

The best-known version of “Let the Good Times Roll” was written by Shirley & Lee in 1956. It has very similar lyrics to the song I was looking for, but has a completely different melody.

BB King has a great song called “Let the Good Times Roll.” Its lyrics go: “Hey everybody lets have some fun. You only live once and when you’re dead, you’re done, so let the good times roll.”

Not it, but fantastic nonetheless.

Of course, there is The Cars 1978 song titled “Good Times Roll” that is totally unlike any of the R&B versions, and was a large part of the soundtrack of my youth: “Let the good times roll, let them knock you around, let the good times roll, let them make you a clown, let them leave you up in the air, let them brush your rock ‘n’ roll hair, let the good times roll.”

That “let them brush your rock ’n’ roll hair” line may be the thing that got The Cars into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Dr. John, Stevie Ray Vaughan and Jimi Hendrix also recorded a song called “Let the Good Times Roll.” The lyrics include: “People talkin’ but they just don’t know. What’s in my heart, and why I love you so. I love you baby like a miner loves gold. Come on sugar, let the good times roll.”

I eventually discovered this song is actually called “Come on” and was written by New Orleans legend Earl King, who wrote the traditional Mardi Gras anthem “Big Chief.”

I never would have figured out that Earl King wrote that tune without the internet, because it has a different title from the version recorded by Hendrix et al. Even Dr. John, who hails from New Orleans, recorded that song as “Let the Good Times Roll.”

But where was the Grateful Dead’s song “Let the Good Times roll?” Nowhere. And then one day it occurred to me to type the lyrics into Google. This should have occurred to me earlier, but it didn’t. And when I typed the opening lyrics into the search engine, bam, all was revealed.

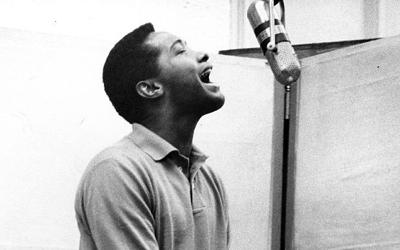

It turns out the song is called “Good Times” and was written and recorded by Sam Cooke. It was released in July 1964, five months before Cooke was shot and killed at the age of 33 by the manager of a motel in California. Despite his early demise, Cooke recorded 30 songs that made the Top 40.

“Good Times” hit No. 1 on the R&B chart and Billboard Hot 100.

The curious thing about “Good Times” is that, despite its commercial success, it did not appear on any Sam Cooke compilations (of which there are several), until a box set called Sam Cooke “Portrait of a Legend” came out in 2003.

For some reason, “Good Times” got buried in his catalogue.

Once I dove into Sam Cooke’s repertoire, I learned the story of the song “A Change is Gonna Come,” which was inspired by Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind” and was released 10 days after his death. The song is regarded as a seminal anthem in the Civil Rights movement.

That’s the way musicology works. You start to dig into a song, and the journey takes you to places you didn’t expect to go (Willie Dixon played the bass, by the way).

So why are so many songs called “Let the Good Times Roll?” Why not “It’s time to rock ’n’ roll” or “Let’s party tonight”?

The answer goes back to New Orleans. The term is the English derivation of the phrase “laissez les bon temps roulez,” which is a tribute to the spirit of New Orleans, and a nod to the important role New Orleans plays in jazz, rock ’n’ roll, blues and country music.

And if you want to dig deeper into New Orleans and its significance in popular music, you have to go back to Louis Armstrong, investigate the French influences of Zydeco music and study the drum circles that slaves held in Congo Square. Welcome to the wormhole of musicology. Let the good times roll.

Commented

Sorry, there are no recent results for popular commented articles.