Where Are You Now: A Recollection of Past and Current Michelle Branch

My first introduction to popular music was through a 100% nineties-made Barbie karaoke machine, a Christmas gift from my sister. The candy-colored marvel came with three cassette tapes: “Female Favorites” (construction cone orange), “Male Artists” (mint green), and “Party Hits” (pastel purple). My personal favorites to belt out in my bedroom, with my mouth much too close to the static-y pink microphone, were “We are Family” by Sister Sledge, “Believe” by Cher, and “…Baby One More Time” by Britney Spears.

In a way, my karaoke machine acted as a catalyst, kick-starting my love for both pop music and women pop-vocalists. My sister saw how much I loved my gift and began to make mix tapes for me to pop into the player. I both blame and thank her for my unhealthy obsession with Britney Spears, that remains unwavering to this day.

HitClips came out in 1999. The small, primordial MP3 players were popularized after McDonald’s distributed them in Happy Meals. Both myself, and every other youth in America, wholeheartedly pined for the musical toy which would play only one-minute long clips of popular songs. The entire concept was flawed and nonsensical.

The music itself was ultra lo-fi, but I begged my mom for one of these things anytime we passed the toy aisle. When she relented, I picked out a small, boom-box-shaped device that came with three clips: The Backstreet Boys’ “Shape of My Heart,” Michelle Branch’s “Everywhere,” and “A Thousand Miles” by Vanessa Carlton. I listened to these clips to death. I listened to them in the bathroom while I organized and selected from my collection of hundreds of sickeningly sweet Lip Smackers every morning, I listened to them at night in my room, and I listened to them enough around my poor parents to where I would catch my mom singing the familiar tunes while working around the house. Eventually, my HitClips boom box stopped working altogether. I literally loved it to death.

When cassette tapes were finally defeated by CDs, I no longer had to park myself by the radio for hours, waiting for my favorite songs to come on so that I could record them. I convinced my dad to buy me a Walkman that you had to hold perfectly flat and still, lest your songs skip.

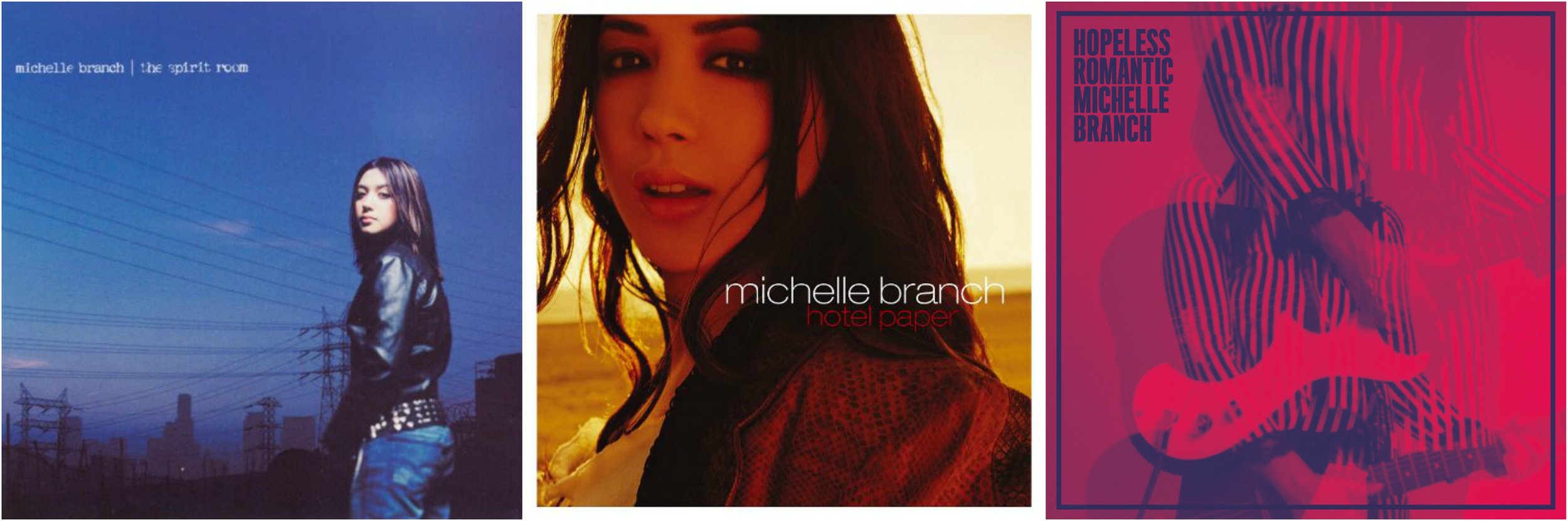

My first CDs were Avril Lavigne’s Let Go, Vanessa Carlton’s Be Not Nobody, and Michelle Branch’s The Spirit Room. And, because it was popular with the kids in my elementary class, I also convinced my dad to let me purchase the collection of songs that hit highest on the charts in 2003, Now 14. I still regard Now 14 as being one of the best Now That’s What I Call Music! compilations to ever be released. On it was power couple Beyoncé and Jay-Z’s “Crazy in Love,” “Stacy’s Mom” by Fountains of Wayne, and two songs by two incredibly important and largely forgotten female-pop singers: “Why Can’t I?” by Liz Phair, and “(There’s Gotta Be) More to Life” by Stacie Orrico.

With my childhood imagination as wild as my crown of frizzy baby hairs, I played out scenarios and visions of my future as a famous pop-singer in my head, world famous and equipped with a headset and a criminal amount of glitter. I made up dance moves and routines with my friends. At my Synagogue’s junk sale, I begged my dad for a cheap, chipped-white painted guitar with broken strings, and attempted (without any success) to write my own songs. During school I lost focus easily, dreaming about being best friends with Vanessa and Michelle (we were on a first-name basis at this point) marveling in our success together. Vanessa Carlton and Michelle Branch were writing the type of songs that made me feel like I understood the things that I desperately wanted to be a part of: love, despair, independence, and womanhood.

In fifth grade, with a closet full of plaid Bermuda shorts (thanks, Mom), sequin covered tops, and maybe even a pair of coral-colored Crocs blinged out with soccer charms, I was desperately trying to fit in at school. The transition from elementary school to junior high was rough for me. It was also rough for my classmates, and caused children to act out due to a confusing combination of new responsibilities, and their changing bodies. When kids were cruel, I still had music. I still had my portable CD player, and the confidence of the women I listened to, and their encouraging lyrics. Christmas of that year, after weeks of convincing, my parents bought me a fifth generation iPod: chunky, clunky, glitchy, and perfect. I was ecstatic. With my sister’s help, the first song I purchased on iTunes and loaded onto the player was, “My Happy Ending” by Avril Lavigne.

Purchasing an iPod for me was possibly the biggest mistake my parents made that year — within a month I had racked up hundreds of dollars in song and music video purchases on my parents’ credit card. They were as livid as my parents can get. In reality, they weren’t that angry, but they did put a password on my iTunes account.

I carried my iPod everywhere. Every night I looked forward to lying in bed, constructing an “On the Go” playlist, and falling asleep with ear-buds in. There were the classics, Britney and Christina. There were the lyrical voices of Vanessa Carlton, Michelle Branch, and Anna Nalick. There were the rebels: Avril Lavigne, Skye Sweetnam, and Ashlee Simpson.

Then there were the big voices and the girl groups: Kelly Clarkson, Gwen Stefani, Nelly Furtado, The Pussycat Dolls, and Danity Kane. These were peaceful times. just me with my music. This was before boys became interesting enough to pursue, before I needed a bra that didn’t come in a three-pack. This was before life got complicated.

Eventually, I started straightening my thick, unmanageable hair, and I traded my Bobby Jack t-shirts for Abercrombie & Fitch. My musical tastes started expanding as well, but I always turned to the girls on my iPod when I needed them most: in times of petty heartbreak that felt very real at the time, during fights with my friends, and when I was angry at the world simply because I was a girl going through puberty and I had a right to be angry at the world when I couldn’t make sense of it.

2008 saw a critical change in pop-music. Katy Perry’s “I Kissed a Girl” topped the charts along with Taylor Swift, which was quickly followed by the infamous 2009 VMA stunt by Kanye West. Listeners were less interested in lyrical ballads and more focused on dance music, songs that were easy to listen to and often heavily produced. Girl groups mostly disappeared. Lady Gaga became an icon. None of these changes were bad, necessarily, but they were changes.

My taste in music shifted, too. I became obsessed with the nineties sad boys: Elliott Smith, Conor Oberst, Jeff Mangum. Despite my sad-boy-Hopt Topic phase, I always held a huge place in my heart for the music I grew up on, and the women that shaped my adolescent years.

When I first heard Michelle Branch was releasing another album, a follow-up to Hotel Paper fourteen years later, I was both nostalgically ecstatic and worried of the changes that would come with over a decade’s worth of time passing since her last album.

I have certainly changed magnificently in the last fourteen years. I’ve lost and gained back confidence, been heartbroken, and have broken other people’s hearts. I’ve definitely gone through a few dramatic changes in style, and most importantly, I’ve figured out how to navigate Victoria’s Secret without giggling in embarrassment.

In the last fourteen years, Michelle Branch got married, had a daughter, and got divorced. She produced an album with Jessica Harp in a short-lived duo, The Wreckers.

Branch also entered “label purgatory” after a record she made in 2009 was denied by her record label for not sounding how fifteen-year-old Branch used to sound. The path that Branch had to take to finally release an album in 2017 was long, rough, and at points, a little soul-crushing.

Hopeless Romantic was co-written and co-produced by Branch’s now boyfriend, Patrick Carney, drummer for The Black Keys. The album is an obvious departure from both Hotel Paper and The Spirit Room.

For one, Branch is now 33 years old. The way that music itself is produced has changed significantly since 2003. The beats are different; the style is slightly reminiscent of Carly Rae Jepsen’s 2015 album E*MO*TION with the influence of the deep, smooth-toned vocals of HAIM. Still, Branch managed to put out an album in 2017, after a fourteen year hiatus. Her new work still made me feel the nostalgic yearn for the simplicity of adolescence. Yet, the maturity of this new record gives me confidence, and helps me believe in the power of a long wait.

Hopeless Romantic is the type of album I want to listen to under my covers in my childhood home, or in the backseat of my parent’s car. It’d be a perfect fit in a mix C.D.with Vanessa Carlton’s “White Houses” and Skye Sweetnam’s “Tangled Up In Me.” It’s a record for long road trips — falling asleep to the flashes of street lamps illuminating one’s face, and the sound of the I-74 vibrating under spinning tires.

Somewhere in a box I still keep the notes I wrote specifically on hotel notepaper. Two years ago I saw Britney Spears live with my sister. Maybe not much has changed, but what has changed has been so good.