The 1619 Project: Changing Our Melody

Adapted from a presentation at Woodlands Community Temple

January 3, 2024 • 25 Tevet 5784

One day, many years ago, while driving my young children around town I, as usual, had music playing in the car. On this particular day I’d put on a playlist of my favorite gospel tunes. I love gospel music and have tried my hand at writing Jewish tunes that are informed by the irrepressible spirit of some of what I think is America’s greatest Christian music. As we were driving along, there was a pause between tunes when I heard a voice from the backseat ask, “Daddy, aren’t we Jewish?”

What can I say? I come by it honestly. First, regarding the lyric content of the songs, I believe in the validity of all religious messages, so long as they are kind, open-hearted and in pursuit of a just society. Second, I’ve always enjoyed a great variety of musical styles. It’s possible that comes from growing up as the youngest of six children in a home where music emerged from every room: my mom listening to Glenn Miller and to Rosemary Clooney, my dad listening to classical, and my siblings turning up the volume on everything from Andy Williams and Claudine Longet to The Beatles, Santana, and Sly and the Family Stone.

Sly and the Family Stone. Marvin Gaye. Isaac Hayes. Earth, Wind and Fire. Just a few of the superstars whose music filled my home throughout my youth. All of them were black. But at the time, I didn’t know that.

In the olden days, when record owners would read album covers over and over again while listening to the vinyl discs inside, I didn’t know that any of these performers were black simply because these weren’t my albums. I fell in love with their music from a distance, as I laid down long lines of Hot Wheels track in the hallways of our home or worked up intricate designs on my Spirograph while sitting at the kitchen table. This music was the background soundtrack to my pre-adolescent years.

What I hadn’t realized, at least not until viewing the music episode of Hulu’s “The 1619 Project” was that tunes that were written and performed by people of color, like American blacks themselves, were usually segregated out of view from my white community in Cincinnati of the 60s and 70s. “The 1619 Project,” which began as investigative reporting for The New York Times Magazine by Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones and has recently become a documentary series on Hulu, very convincingly asserts that our country’s entire history, to this day, links the consequences of slavery and the contributions of Black Americans in profound ways that still demand a complete reckoning and change of national behavior.

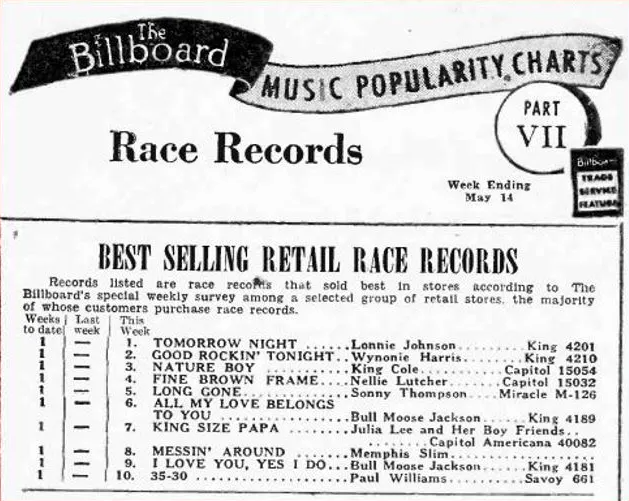

My brothers listened to alternative FM progressive rock stations which, I think, were less subject to the subtle acts of discrimination that AM radio employed, including playing hit parade listings that excluded what was actually called by Billboard (and I remember them being listed as such in our local paper) “Race Music” or, a little bit later and, I suppose, less inflammatory, “Soul Music.”

I can tell you that, while I was growing up in Cincinnati, “Soul Music” was never played on any AM radio in my home or in the public places that I frequented.

I never noticed.

I really had no idea that my life was a pretty clear reflection of an America that had only barely moved on from slavery. While I never said or did anything that was demonstrably racist, and I never witnessed such things, my recent involvement with “The 1619 Project,” namely public conversations in our local library, each session facilitated by one black and one white community figure, and specifically my conversations with Rev. Freedom Weekes of Children’s Village in Dobbs Ferry as he and I prepared our shared presentation, I’ve only now come to understand the role that I’d had no idea I had played in discriminatory living.

Prior to my and Rev. Weekes’ presentation at the library, we met for lunch and spent a delightful few hours getting to know each other. We spoke openly about our youth, and the ways in which each of us had experienced and been affected by black-white relationships. It was during this conversation that I heard my own words about the racism which I had been part of.

I was stunned by my self-revelations.

I’m going to pause here for a moment to share with you one of the great pieces of anti-racist pop. While Sly and the Family Stone was better known for their funk and psychedelic tunes, “Everyday People” crossed over into the mainstream, crossed over the racial divide, to deliver its message of acceptance and love.

Now I’m a pretty nice guy and I don’t generally harbor anger or grudges for superficial, super-uninformed, super-selfish reasons. So I asked Rev. Weekes what I could do to be a better ally and he said to me, “Talking like this is a great first step.”

So let me urge you to do the same. Find a gathering where these kinds of conversations are taking place. Listen to others’ stories. Share your own. Be honest about it. And ask the question, “How can I better support people of color in my personal and public life?” Hopefully, you’ll find it as illuminating and challenging an experience as I have. But I want to emphasize how important an experience it is.

Since retiring, I’ve spent most of my time studying and writing music. It’s been a thrill and a luxuriant dream come true. I struggle with the value of my endeavors though. After 26 years as a congregational rabbi, it feels self-indulgent and not terribly helpful to society to be spending all my time in a little room with music (and Charlie) filling my days. But I have to remember that, despite my being 67 years old, I am still quite the newbie at this music thing. I have to give myself the time to just be a student, to acquire the skills I need to be able to bring my art to bear on the important issues of our day, something I very much want to do. In the meantime, I’m watching the world around me and am just starting to dip my toes into creating music that is responsive to these times.

Ellen and I recently wrote a piece of music together called “Panim El Panim,” which is a phrase the Torah uses to describe Moses’ face-to-face encounters with God. The song’s lyrics urge us to carefully consider how we interact with one another, and to understand that it’s when we connect with others — when we connect compassionately, lovingly, and with common humanity — “these are the moments,” the song suggests, when God is here. The piece is every bit the kind of social commentary that I’ve been used to sharing in my teaching, in my preaching, and in my writing. I hope to find a way to continue such social commentary through my music. To help further the conversation about making the world a better home for everyone.

I have no idea if I’ll ever be good at this. I’ve begun researching and thinking about a new piece that will be based on the White Rose, the resistance group that operated in Munich, Germany, for less than a year in 1942-43, urging active opposition to the Nazis but which ceased when its leadership was caught and executed. If the poet in me can get this right, the song will have as much to say about our world today as it will about the world then.

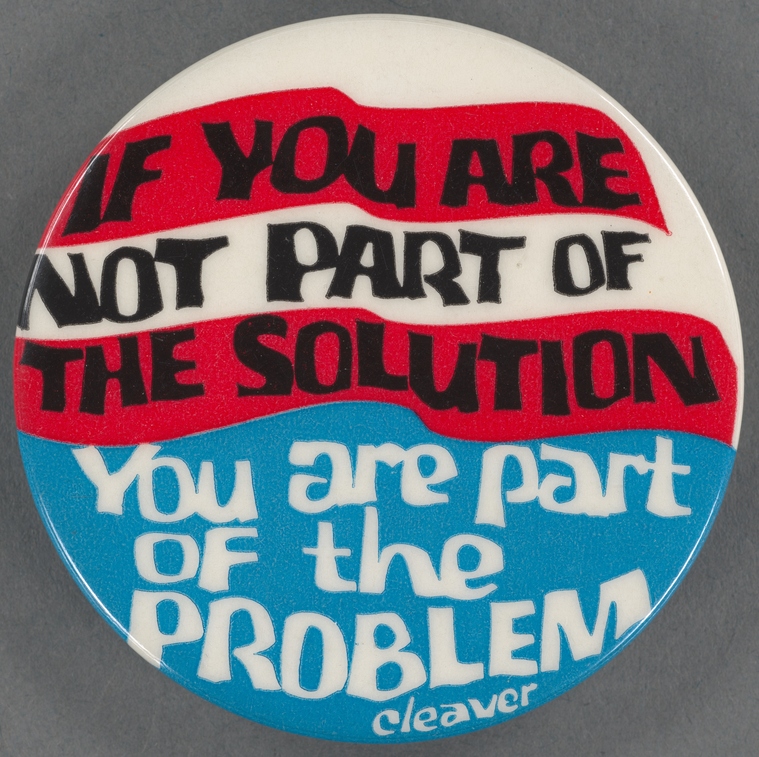

I don’t know how to solve the problem of race. All I know is that I can at least do something to try and move the needle, and to try and make sure that I’m not part of the problem.

Why do I care about racism?

Well, probably most significantly, my family cared. My father was a doctor who took care of people his entire life. My mother marched with Dr. King. And my brothers drafted little-kid me into their anti-Vietnam War activities. I am a product of a family whose values may have made it likely, if not inevitable, that I would want to help, not hinder.

Second, Jewish tradition teaches us to care. The book of Exodus tells the story of the Jewish people’s decline and descent into Egyptian slavery, and also the story of our rescue and our redemption. As we left Egypt, it became the story of our stopping at Mount Sinai and pledging ourselves for all generations to accept others and to welcome difference.

Because we know.

We know what it’s like to be stripped of freedom, and thank God what it’s like to get it back. Judaism teaches us again and again that it is our responsibility to make sure no one has to ever endure cruelty — at the very least, to not have to endure it forever.

Third, the world needs us. Regardless of religion or family of origin, the world needs us to care. It needs us to respond, to help where we can. And even when we can’t help, to name it, to call out injustice for what it is and to keep doing so until the world no longer turns a blind eye.

I don’t know whether one person’s deeds of, in this case, anti-racism are better than another’s. Sure, it seems like it would be more worthwhile to change a law than to write a song. But how are we to know who is affected by our actions? Someone might grow up to be a Supreme Court Justice because, once upon a time, they were inspired by a song!

I have always loved the music of The Beatles. I was only seven when they landed in the U.S. for the first time. But their music had already been part of that home-based soundtrack I mentioned. So in 1968, when the song “Blackbird” was released on the White Album, I was exposed to their very British view of American prejudice toward blacks. “Blackbird singing in the dead of night, take these broken wings and learn to fly.” The Beatles had seen how America treated people of color, and they recorded “Blackbird” to let us know that they’d seen, and that they hoped we’d finally do something about it.

Did “Blackbird,” which I must have heard a thousand times in my youth, embed itself inside my heart, so that one day I would want to be part of “The 1619 Project”? I can only give you a maybe on that. But I sure am glad that they put that song out into the world. Just as I’m glad to have participated in my conversations with Rev. Freedom Weekes.

Vayomer el amo … and Pharaoh said to his people … hinei am b ’nai Yisrael rav v’atzum mimenu … “Look, the Israelite people are much too numerous for us … hava nit-chak-mah lo … let us deal shrewdly with them.” (Exodus 1)

It shouldn’t have required us to know what it feels like to be the stranger, to be scorned and outcast, in order to want to do right by others. But we were the stranger and, because of that, we carry a special knowledge and a special obligation.

We may not get it right. God knows, there’ve been many times when I’ve unwittingly hurt others. But we have to keep trying, keep learning, keep getting closer to each of us producing the art, in whatever form it takes, that will shape this world into the Garden of Eden — for everyone — that God meant for it to be.

Billy

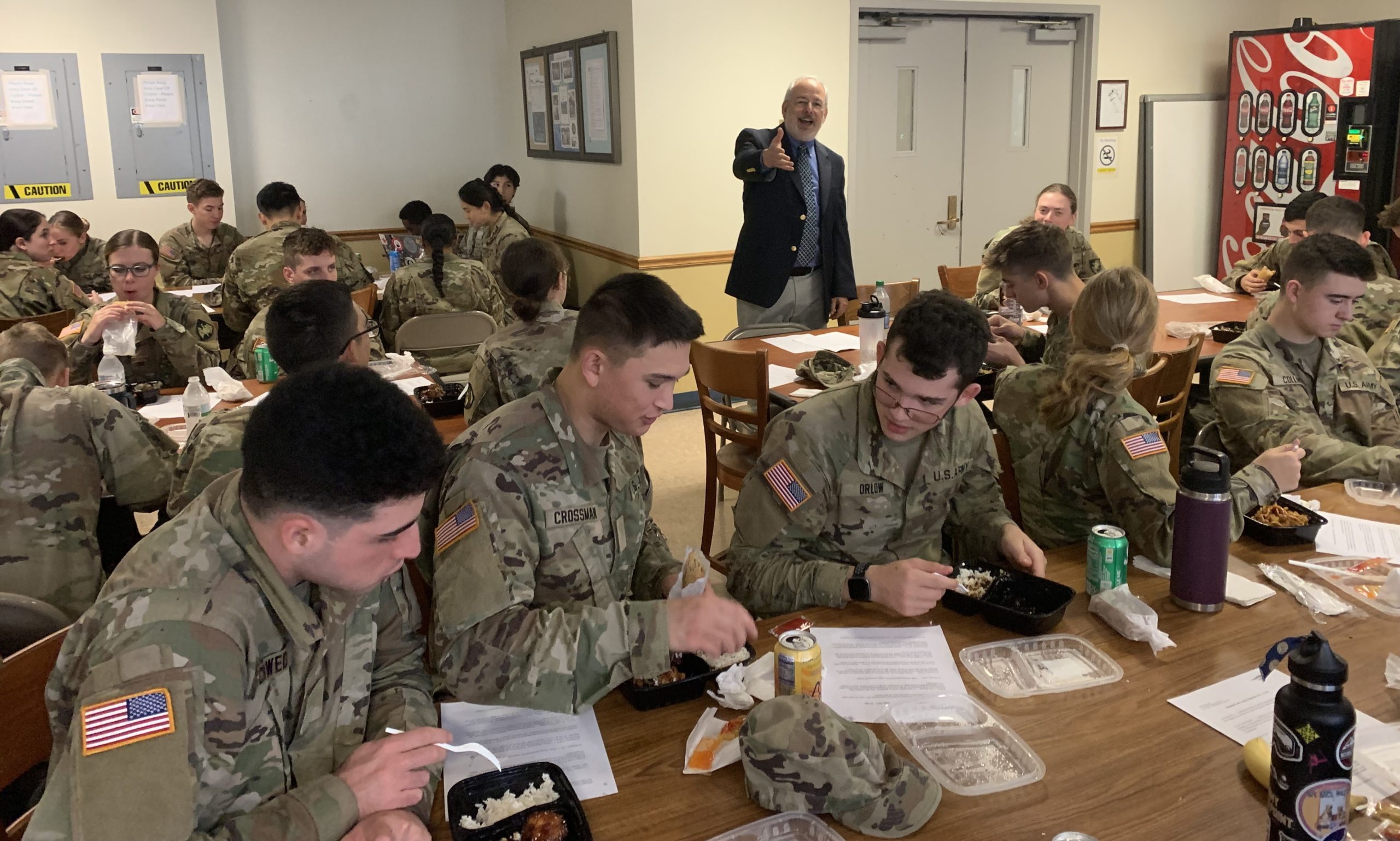

And that’s how I found myself at West Point for lunch this week.

And that’s how I found myself at West Point for lunch this week. The young people at West Point are enrolled in program that grooms them to become leaders, militarily for a while and then perhaps something else when their period of service is complete. While they train, it’s crucial that they think about what it means to be a leader. Giving troops the orders that may determine whether young men and women live or die, this is certainly part of the military leader’s job description. But remaining approachable — especially by those whose lives might one day be placed in the line of danger — preserving and nurturing those parts of themselves that will allow a solder to bring them their problems, that is extraordinary leadership.

The young people at West Point are enrolled in program that grooms them to become leaders, militarily for a while and then perhaps something else when their period of service is complete. While they train, it’s crucial that they think about what it means to be a leader. Giving troops the orders that may determine whether young men and women live or die, this is certainly part of the military leader’s job description. But remaining approachable — especially by those whose lives might one day be placed in the line of danger — preserving and nurturing those parts of themselves that will allow a solder to bring them their problems, that is extraordinary leadership.

The world was changing. A ton of that change would be for the better, and I was growing up right in the middle of it!

The world was changing. A ton of that change would be for the better, and I was growing up right in the middle of it!

Now while that might not sound very interesting to you, do note that Cincinnati sat right on the northern bank of the Ohio River. On the other side was Kentucky.

Now while that might not sound very interesting to you, do note that Cincinnati sat right on the northern bank of the Ohio River. On the other side was Kentucky. For a Cincinnati kid, other than Skyline Chili and Graeter’s Ice Cream, nothing makes me prouder of my midwest upbringing. And at this dangerous moment for America’s immigrant population, that Woodlands is considering becoming a temporary refuge, a stop on a new Underground Railroad if you will, for immigrant families who fear arrest and deportation, not much could make me feel prouder were this congregation to choose to do such a brave thing.

For a Cincinnati kid, other than Skyline Chili and Graeter’s Ice Cream, nothing makes me prouder of my midwest upbringing. And at this dangerous moment for America’s immigrant population, that Woodlands is considering becoming a temporary refuge, a stop on a new Underground Railroad if you will, for immigrant families who fear arrest and deportation, not much could make me feel prouder were this congregation to choose to do such a brave thing. Also a favorite moment of mine in the leveling of human indifference in America is the New Deal. While this wasn’t a Cincinnati deal, and it was well in place long before I was even born, the New Deal – a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt between the years 1933 and 1939 – changed this country as it struggled to emerge from the Great Depression, providing support for farmers, the unemployed, young people and old people through the Works Progress Administration, fair housing standards, the creation of a minimum wage, and Social Security, which allowed for the possibility that old age wouldn’t have to be a time of poverty and despair.

Also a favorite moment of mine in the leveling of human indifference in America is the New Deal. While this wasn’t a Cincinnati deal, and it was well in place long before I was even born, the New Deal – a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt between the years 1933 and 1939 – changed this country as it struggled to emerge from the Great Depression, providing support for farmers, the unemployed, young people and old people through the Works Progress Administration, fair housing standards, the creation of a minimum wage, and Social Security, which allowed for the possibility that old age wouldn’t have to be a time of poverty and despair. Across the years, Sesame Street would teach us about the natural and un-offensive beauty of breastfeeding as popular singer-songwriter Buffy Sainte-Marie introduced her son, who carried the exotic and impressive name Dakota Starblanket Wolfchild, lovingly and tenderly became the first baby to ever be nursed on national television. President Bill Clinton and Kami, an HIV-positive muppet, delivered a stereotype-busting message about having friends with AIDS. There have been episodes that introduced the young audience to a boy with Down syndrome, a child explaining the parts of her wheelchair, a muppet whose dad was incarcerated in jail, an Afghani Muppet who promoted girls’ rights and the importance of providing them with an education. In the 1980s, characters Susan and Gordon Robinson announced that they’d adopted a son named Miles, and in 2006, “Gina” announced she was adopting a little boy from Guatemala. And perhaps our favorite muppet, Julia, who has autism and was created by Woodlands member Leslie Kimmelman, joined the Sesame Street cast. With these episodes, characters and so much more, Sesame Street has championed diversity and inclusion, introducing the youngest members of American society to these vital understandings about the beauty of difference, and the essential commonalities that persist between us all.

Across the years, Sesame Street would teach us about the natural and un-offensive beauty of breastfeeding as popular singer-songwriter Buffy Sainte-Marie introduced her son, who carried the exotic and impressive name Dakota Starblanket Wolfchild, lovingly and tenderly became the first baby to ever be nursed on national television. President Bill Clinton and Kami, an HIV-positive muppet, delivered a stereotype-busting message about having friends with AIDS. There have been episodes that introduced the young audience to a boy with Down syndrome, a child explaining the parts of her wheelchair, a muppet whose dad was incarcerated in jail, an Afghani Muppet who promoted girls’ rights and the importance of providing them with an education. In the 1980s, characters Susan and Gordon Robinson announced that they’d adopted a son named Miles, and in 2006, “Gina” announced she was adopting a little boy from Guatemala. And perhaps our favorite muppet, Julia, who has autism and was created by Woodlands member Leslie Kimmelman, joined the Sesame Street cast. With these episodes, characters and so much more, Sesame Street has championed diversity and inclusion, introducing the youngest members of American society to these vital understandings about the beauty of difference, and the essential commonalities that persist between us all. Let me share with you one more shining moment in the history of America’s march toward becoming a gleaming beacon of acceptance and hope. It actually started in Europe during the 19th century but gradually found its way to America, actually, you guessed it, to Cincinnati! That’s the temple where I grew up. While it wasn’t the first Reform congregation in America (that was in Charleston, South Carolina), it was Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise who came to Cincinnati, wrote the first Reform prayerbook, founded the Union of American Hebrew Congregations (now the Union for Reform Judaism), built Plum Street Temple, established Hebrew Union College to educate and ordain American rabbis, and founded the Central Conference of American Rabbis which gave these HUC graduates an avenue for mentorship and support throughout their careers.

Let me share with you one more shining moment in the history of America’s march toward becoming a gleaming beacon of acceptance and hope. It actually started in Europe during the 19th century but gradually found its way to America, actually, you guessed it, to Cincinnati! That’s the temple where I grew up. While it wasn’t the first Reform congregation in America (that was in Charleston, South Carolina), it was Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise who came to Cincinnati, wrote the first Reform prayerbook, founded the Union of American Hebrew Congregations (now the Union for Reform Judaism), built Plum Street Temple, established Hebrew Union College to educate and ordain American rabbis, and founded the Central Conference of American Rabbis which gave these HUC graduates an avenue for mentorship and support throughout their careers. Every year, when Martin Luther King Day arrives, I thank my lucky stars to be living in a country that sets its sights for the loftiest of dreams, that learns from its mistakes, and that continually strives to build a nation that stands firmly on a foundation of acceptance, understanding and, barring the wholesale acceptance of those first two, on hope … that the day will come when we complete the building of a United States that offers these promises to everyone.

Every year, when Martin Luther King Day arrives, I thank my lucky stars to be living in a country that sets its sights for the loftiest of dreams, that learns from its mistakes, and that continually strives to build a nation that stands firmly on a foundation of acceptance, understanding and, barring the wholesale acceptance of those first two, on hope … that the day will come when we complete the building of a United States that offers these promises to everyone. A year ago, both tragedy and profound beauty struck at the heart of the United States of America. On a Shabbat morning in October, at the Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh, fear and sadness blanketed their lives, rapidly sending tremors of concern and shared sympathy across our nation and across the world. One week later, hundreds of synagogues hosted crowded services that were attended by Americans of every stripe who simply wanted to stand and be counted among the kind and inclusive of our nation.

A year ago, both tragedy and profound beauty struck at the heart of the United States of America. On a Shabbat morning in October, at the Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh, fear and sadness blanketed their lives, rapidly sending tremors of concern and shared sympathy across our nation and across the world. One week later, hundreds of synagogues hosted crowded services that were attended by Americans of every stripe who simply wanted to stand and be counted among the kind and inclusive of our nation.

Here’s a photo of Daryl Davis standing with Richard Preston, who participated in the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, two years ago. Here you can see the two of them visiting the Smithsonian Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington. First Davis invited Preston to his home. In time, Preston invited Davis to his wedding. “That’s a seed planted,” Davis said, as he continues his truly sacred work of bridging the divides between people.

Here’s a photo of Daryl Davis standing with Richard Preston, who participated in the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, two years ago. Here you can see the two of them visiting the Smithsonian Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington. First Davis invited Preston to his home. In time, Preston invited Davis to his wedding. “That’s a seed planted,” Davis said, as he continues his truly sacred work of bridging the divides between people.

A cursory look online reveals that a lot of people write lists of hoped-for accomplishments. Some do it for themselves; many do so to teach others (or to get you to buy whatever life-improvement product they’re peddling). I looked over some of these lists and pulled out some that I thought were worth mentioning here.

A cursory look online reveals that a lot of people write lists of hoped-for accomplishments. Some do it for themselves; many do so to teach others (or to get you to buy whatever life-improvement product they’re peddling). I looked over some of these lists and pulled out some that I thought were worth mentioning here.

Once upon time, an anonymous rabbi was walking in the woods behind the dog park with his best pal, Charlie. He was soon joined by a man who lived nearby but who was born and raised in Ireland. The man was planning to go back and visit his brothers, two of a total of seven, who still live in Cork. But he couldn’t decide which brother to stay with. The very wise rabbi suggested he stay with whichever one will be less bothered by his choice. The man said that neither brother would be happy. The exceedingly wise rabbi suggested he invite both brothers to come stay with him. The man said that would never work. The increasingly impatient rabbi asked why. The man said, “Because my brothers haven’t spoken to each other in years.” The rabbi thought, “This is why I like dogs – they may never speak but they never stop loving either.”

Once upon time, an anonymous rabbi was walking in the woods behind the dog park with his best pal, Charlie. He was soon joined by a man who lived nearby but who was born and raised in Ireland. The man was planning to go back and visit his brothers, two of a total of seven, who still live in Cork. But he couldn’t decide which brother to stay with. The very wise rabbi suggested he stay with whichever one will be less bothered by his choice. The man said that neither brother would be happy. The exceedingly wise rabbi suggested he invite both brothers to come stay with him. The man said that would never work. The increasingly impatient rabbi asked why. The man said, “Because my brothers haven’t spoken to each other in years.” The rabbi thought, “This is why I like dogs – they may never speak but they never stop loving either.”

Who could have known what would transpire at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh only six days ago, and that we would be gathering here this evening to remember the eleven men and women whose lives were ruthlessly taken by a vicious, hate-filled killer? And although our country has been here far too many times before – notably, the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, FL, the Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino in Las Vegas, the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, the Kroger killings this past week in Jeffersontown, KY, and the Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, CT – you probably don’t know this, but also won’t be surprised to learn that there have been 297 mass shootings in our country thus far in 2018.

Who could have known what would transpire at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh only six days ago, and that we would be gathering here this evening to remember the eleven men and women whose lives were ruthlessly taken by a vicious, hate-filled killer? And although our country has been here far too many times before – notably, the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, FL, the Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino in Las Vegas, the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, the Kroger killings this past week in Jeffersontown, KY, and the Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, CT – you probably don’t know this, but also won’t be surprised to learn that there have been 297 mass shootings in our country thus far in 2018. Camila, I’ve known your parents for a while now. Your dad became a Bar Mitzvah here, your parents got married here, and your mom became Jewish here. And now they’ve brought you here! And at just the right time too. I’m glad you don’t understand what I’m saying right now, but everyone else does, and this is important. After something terrible happens in our world – as with last Saturday’s shootings in Pittsburgh and Wednesday’s shootings in Kentucky – it simply must be followed by something that affirms what is good and hopeful in our lives. Which is where you come in, little one. Your mom and dad are good folks. They care about you, and will always care about you. But they also care about others, and they’re going to teach you about that in the years ahead, and we’re going to help them.

Camila, I’ve known your parents for a while now. Your dad became a Bar Mitzvah here, your parents got married here, and your mom became Jewish here. And now they’ve brought you here! And at just the right time too. I’m glad you don’t understand what I’m saying right now, but everyone else does, and this is important. After something terrible happens in our world – as with last Saturday’s shootings in Pittsburgh and Wednesday’s shootings in Kentucky – it simply must be followed by something that affirms what is good and hopeful in our lives. Which is where you come in, little one. Your mom and dad are good folks. They care about you, and will always care about you. But they also care about others, and they’re going to teach you about that in the years ahead, and we’re going to help them.

I was thinking of times, growing up in Cincinnati, when my parents opened our home to guests. I remember when I was really little that they often hosted parties during which I was ordered to stay upstairs and out of sight. Later, in my early teens, I remember my older brothers welcoming traveling hippies who would regale me with stories of their having attended Woodstock in 1969. But besides that, our house was most frequently a shelter for myriad cats and dogs. I couldn’t find a photograph from frequent times when entire litters of cats filled our home, but here are some snapshots of me and my siblings and some of the guests who stayed and stayed and stayed, teaching me important lessons in hospitality, about offering food, a place to rest, opportunities to get outside and play, and, of course, lots of love.

I was thinking of times, growing up in Cincinnati, when my parents opened our home to guests. I remember when I was really little that they often hosted parties during which I was ordered to stay upstairs and out of sight. Later, in my early teens, I remember my older brothers welcoming traveling hippies who would regale me with stories of their having attended Woodstock in 1969. But besides that, our house was most frequently a shelter for myriad cats and dogs. I couldn’t find a photograph from frequent times when entire litters of cats filled our home, but here are some snapshots of me and my siblings and some of the guests who stayed and stayed and stayed, teaching me important lessons in hospitality, about offering food, a place to rest, opportunities to get outside and play, and, of course, lots of love. But also enshrined in our laws was an insistence on welcoming those who are fleeing danger in their own lands. Since World War II, we can be proud that more refugees have been granted asylum in the United States than in any other nation. But today, applications for asylum are under siege, children are being taken from their parents, and deportations of current residents are occurring everywhere including, only eighteen miles from here, the caretaker of Temple Bet Torah in Mount Kisco where Armando Rugerio has worked for twenty years, raised two children, and now languishes in an Albany jail as he awaits a final determination of his fate.

But also enshrined in our laws was an insistence on welcoming those who are fleeing danger in their own lands. Since World War II, we can be proud that more refugees have been granted asylum in the United States than in any other nation. But today, applications for asylum are under siege, children are being taken from their parents, and deportations of current residents are occurring everywhere including, only eighteen miles from here, the caretaker of Temple Bet Torah in Mount Kisco where Armando Rugerio has worked for twenty years, raised two children, and now languishes in an Albany jail as he awaits a final determination of his fate. Eloheinu v’elohei avoteinu v’imoteinu … dear God and God of our ancestors, God of New York and God of Connecticut, God of the Jews and God of the Muslims, God of the comfortable and God of the afflicted, what goodness You have implanted in Your magnificent world! May we open our homes, our towns, our nation, to ensure that all life is honored and protected. Regardless of differences between ourselves and our neighbors, may we understand that we’re not so different that we can’t look into the eyes of another and see the faces of our sisters and our brothers. May the people of our two synagogues always be among the Righteous of the Nations who stand up and proclaim, “Besa.” My word is my promise. My faith is my honor. Humanity is to be cherished. I will do so for each and every one of them.

Eloheinu v’elohei avoteinu v’imoteinu … dear God and God of our ancestors, God of New York and God of Connecticut, God of the Jews and God of the Muslims, God of the comfortable and God of the afflicted, what goodness You have implanted in Your magnificent world! May we open our homes, our towns, our nation, to ensure that all life is honored and protected. Regardless of differences between ourselves and our neighbors, may we understand that we’re not so different that we can’t look into the eyes of another and see the faces of our sisters and our brothers. May the people of our two synagogues always be among the Righteous of the Nations who stand up and proclaim, “Besa.” My word is my promise. My faith is my honor. Humanity is to be cherished. I will do so for each and every one of them.