A Timeline of Chinese Porcelain: Neolithic to Modern

Thinking of starting a collection of Chinese porcelain? Here are the periods, dynasties and styles to look out for.

The extraordinary development of Chinese porcelain began more than a thousand years before the secret of how to make it was discovered in the West. We know from archeological discoveries that the people of China were making pottery as long ago as the Neolithic period (as early as the fourth millennium B.C, or at least five thousand years ago.) These were the Yang-shao and Longshan cultures, named after the villages where the first pieces were excavated. Food and wine storage would have been necessary from the dawn of agriculture 10,000 years ago, and these early cultures made vessels for practical or ritual use that were beautifully shaped and decorated. These pieces were made from coils, a pad and beater and sometimes a wheel. They were low fired and often decorated in pigments and sometimes etched with geometric designs.

Related: Chinese Porcelain: How to Build a Collection

It would be logical to assume that the decoration of Chinese pottery and porcelain became more complex as the glaze and firing technology improved over the generations. This is often the case, but there are many exceptions to this assumption. Much would depend upon the intended purpose of the piece. Is it meant for a high ranking official, an Emperor even or maybe just as a practical provincial item? Perhaps it is intended for export to the Middle East, South East Asia, Europe or the Americas. Some elements of decoration depend upon the sources of minerals used for pigments, either through geography or trade. Other elements of the increased glaze color range are the results of centuries of experimentation and possibly accidental discovery.

When glaze technology was limited, the decoration of an object could be expressed through its shape, carving, relief application or molding under a limited palette of monochrome glazes. Gradually, pigments and technology became ever more sophisticated. Alternating oxygen levels in kilns with iron, lead and copper glazes resulted in a greater variety of hues. Slip painting, underglaze pigments and finally overglaze enamels were added to the repertoire. Eventually, especially in Jingdezhen (the imperial kilns), the role of potter and decorator were split so that each could specialize and perfect his craft.

Related: Jade: An Asian Talisman

As one looks to begin collecting, it is important to know the various periods and dynasties of mainland China and what kind of ceramics one might expect to find from that period. One important factor to bear in mind is that the Chinese often copied earlier periods of ceramic making. This was not necessarily to deceive, but out of reverence for that particular period that was possibly in fashion. It is common for decline to occur towards the end of a dynasty for obvious reasons - lack of patronage, confidence and often the distraction of unrest. Quality can vary enormously during each period with the finest pieces being made for the Imperial Palace or the highest orders of society, medium quality pieces for lower ranking officials or export and so on. Then there are some merely decorative or functional pieces.

Here is a comprehensive guide to the different periods and what porcelain was produced in each:

Neolithic Period (8,500-2070 BC )

During this period, pieces were originally made using coiled clay until the introduction of potter’s wheel with the Longshan culture. There was an improvement of kiln design (greater number of smaller vents, rather than fewer larger ones), so consequently there were fewer firing faults to the surface.

Ceramics were unglazed painted pottery with geometric designs. The vessels are mostly functional, but surviving pieces are beautifully designed and the bodies are evenly formed. The pigments used are black, dark brown, ochre and rusty reds and are sometimes terracotta colored. Some shapes are quite strange and anthropomorphic in nature, and these are often more affordable than later pieces.

Related: How to Value Your Objects in a Click of a Button

Shang Dynasty (1600-1046 BC) and Zhou Dynasty (1050-221 BC)

This period, known as the Bronze Age, is dominated by bronze casting, which became very sophisticated. However, in the northern provinces, kiln development progressed further with the introduction of high fired white kaolin clays. There was an increased use of the potter’s wheel and early examples of glazes appear that were leadless and fused at temperatures between 1,100-1,200 degrees Celsius.

Shang pieces are rare (they're really only found in museums) and often in shapes of censers and jars. The decoration is mostly horizontal grooves from turning on a wheel with additional geometric detail like lozenges, chevrons, and stamps with scrolling motifs. The glazes tend to be light in color and translucent.

Han Dynasty (221 BC-220 AD)

Now, hard glazed ware had become established and lead glazes appear that were fired at low temperatures and are more opaque. The glazes cover the earthenware well, disguising the body color and making it impermeable. The shapes are often globular vessels with handles often luted on to the shoulders.

The larger vessels often have relief bands around the shoulders that are incised with lozenge designs, scrolls and birds. Combed wavy lines are often found around the neck. The glazes are mostly brown and green, with green glazed vessels decorated with applied reliefs. Both glazed and unglazed painted pottery have figures, animals and miniature models of farmsteads and carts. These were used during burial to accompany the dead in their tombs. The unglazed pottery vessels are painted in red and black pigments with stylized zoomorphic designs and scrolls.

Tang Dynasty (618-907)

At this point, earthenware is superseded by stoneware, preparing the way eventually for porcelain. The high fired ceramics with hard glazes contain iron oxide, with the black being fired in a cleaner and more oxygen-rich atmosphere and the green in a kiln with reduced oxygen. 9th century greenware from the Yue kilns in northern Zhejiang province is highly prized because it was used by the emperor in Buddhist ceremonies and featured in several Tang poems. There’s also the sudden appearance of cobalt-blue glazes that were probably imported from the Near East in the form of glass cabochons.

During this period, monochrome vases are elegantly shaped and carved with intricate foliate scrolls or simpler overlapping leaves (lappets). There was also production of circular boxes, globular jars, stands and zhadou (spittoons). Sancai (three-color) wares also appear, usually in green, amber and straw or buff tones, and some early cobalt blue. The glazed and painted pottery figures and animals become more realistic with a sense of movement. Glazes are often splashed on with seemingly careless abandon, or sometimes the glaze just runs in the firing.

Liao Dynasty (907-1125), Song Dynasty (960-1279) and Jin Dynasty (1115-1234)

During these periods, there’s a proliferation of wealthy patronage mainly in the north. Due to this, there’s an industrialization of ceramic production and kilns begin to specialize in output. There’s an evolution of Ding (white) ware and use of copper in Jun ware.

Monochromes flourished in this period, including white Dingyao bowls, dishes and saucers carved and molded with phoenix and foliage motifs. Stoneware bowls were applied with rich brown glazes in the ‘hare’s fur’ style (brown glazes with milky white streaks) and could have stencils or be decorated with leaf and floral motifs. Elegant vases, jars, saucers and censers with early celadon and highly prized crackle glazes also appeared.

Related: 5 Things You Didn't Know About Ceramics

Yuan Dynasty (1279-1368)

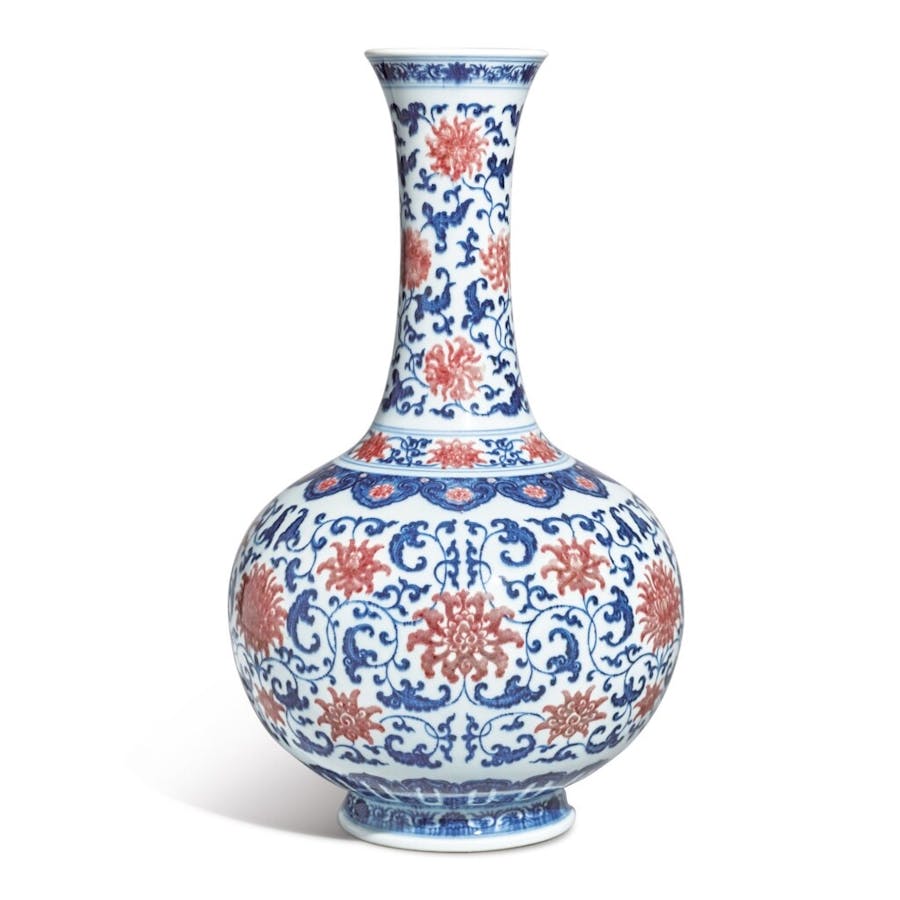

The Mongol Empire was established by Kubla Khan during this dynasty, bringing an Islamic influence. At this point, there’s a greater use of underglaze-blue and underglaze-red, and Islamic motifs appear with production concentrated at Zhingdezhen.

There’s further specialization with different workshops for different processes and extensive use of molds for shaping and decoration. The first use of cobalt blue as an underglaze pigment shipped from Kashan is identified. Also, the Fahua technique (raised slip lines to stop enamels from running into one another) is developed.

There’s still some continuation of Song-style pieces, but there's a greater quantity of qingbai (very pale blue thin porcelain.) There’s also more use of celadons, white and Jun glazes, and an increase in blue and white chargers and jars. Large vases and meiping are made in three sections with carved or molded designs such as dragons and exotic foliate scrolls. Islamic Influence can be seen on the blue and white designs for the Near East market, as well as for the Imperial court.

Ming Dynasty (1368-1644)

By now, techniques are refined and perfected, and mass production of blue and white porcelain increases to astonishing levels. Copper-red production gradually deteriorates and is superseded by the use of brighter iron-red as an over-glaze. Quality control becomes stringent during the reign of Chenghua (1465-1487), with very few intact pieces existing from this reign. From the 15th century, overglaze enamels are used to create multi-colored pieces, and imperial patronage and reign marks appear.

From this period, one can find blue and white pieces with reign marks, and the shapes include dishes, jars, and bottle vases, often copying Middle Eastern silver or metalware prototypes, decorated with dragon, phoenix, lotus scrolls, fruiting sprays, and Three Friends of Winter (bamboo, prunus and pine).

Related: 8 Sensational Flea Market Finds

From this period come the first commissions for the European market from Jesuit priests. Doucai (underglaze-blue with enamels) porcelain was highly admired and collected by the Imperial court. In the latter years of the dynasty the painting quality starts to become less precise. This is the start of mass export shipments to Europe, particularly of ‘Kraak’ porcelain (blue and white ware.)

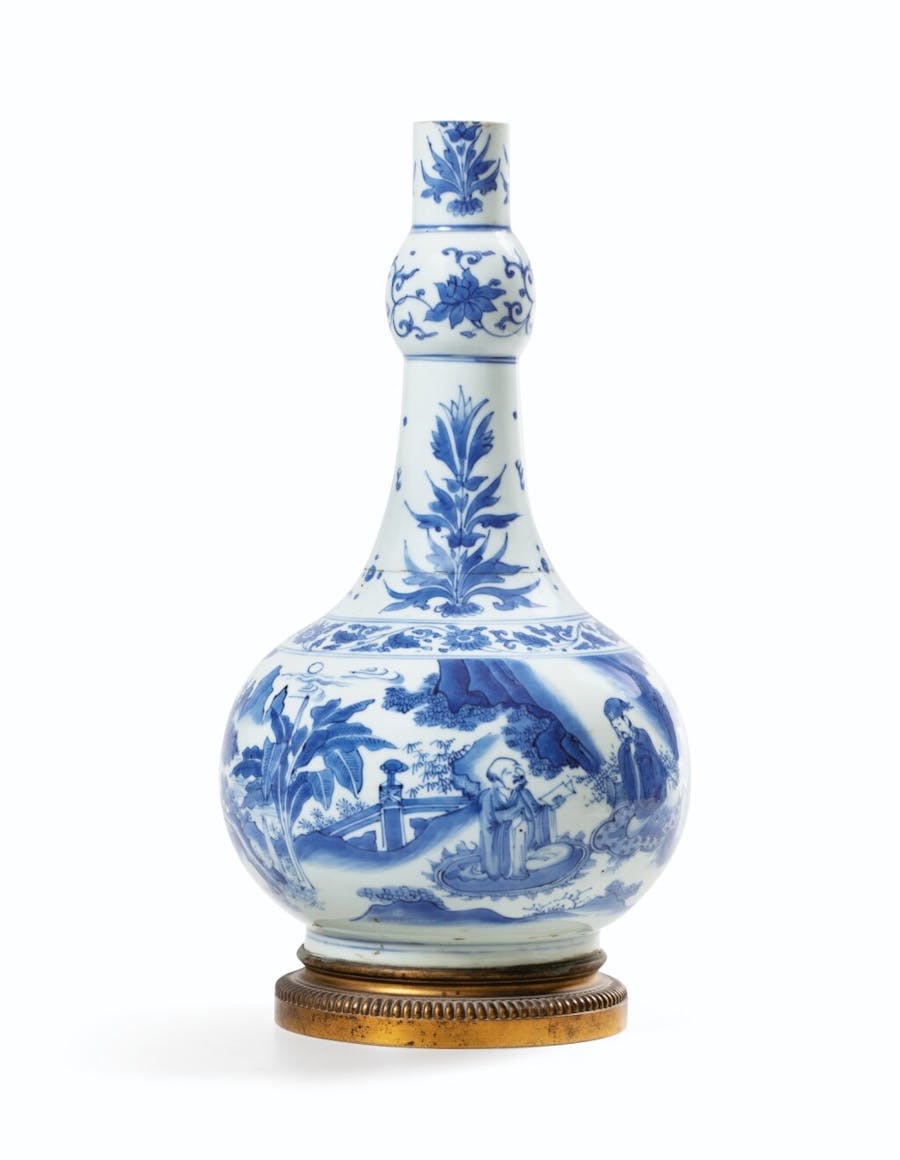

Transitional Period (mid-17th century)

This was a period of instability between dynasties, with less Imperial patronage. Porcelain demand came from scholars, dignitaries, regional rulers and the overseas market.

Due to this, from this era one will find less Imperial ware and more items made for scholars, provincial ware and export. In turn, there are more depictions of scholars, figures, and landscapes and scenes from known literature or ‘Romances’ on the porcelain.

Qing Dynasty (1644-1912)

By the Qing Dynasty, there’s a distinction between imperial kilns and those making items for export or the domestic market. There are better labor conditions under the patronage of emperor Kangxi, who re-opened and financed the kilns at Zhingdezhen. Cobalt ores are no longer imported but sourced from the Zhejiang province. These kilns produced vivid shades of bright underglaze-blue, which is characteristic of pieces from the Kangxi (1662-1722) period. At the very end of Kangxi’s reign pink (rose) enamel was imported from Europe.

Related: Expert Jean Gauchet Explains Kangxi Porcelain

Lemon-yellow glaze was developed in this period. Technically difficult to achieve, it is an improvement on the earlier imperial yellow glazes of the Ming dynasty. The refinement of the glaze involved combining the antimoniate of iron with tin oxide - a difficult process that had a high chance of failure. Objects such as these were reserved for imperial use only, except for a few pieces that found their way abroad as diplomatic gifts. The use of a five-claw dragon was an image to convey Imperial power.

Related: Snuff Bottles: Still up to Snuff

The highest quality of porcelain production was achieved in the 18th century. China-mania occurred in Europe with enormous prices paid for porcelain. Augustus the Strong of Saxony allegedly traded a regiment (Dragoon) of soldiers for 151 pieces of porcelain including a set of 16 large blue and white jars and covers. European East India companies arrive to trade and treaty ports for Europeans (known as Bunds) open in 1785 and to Americans in 1830. There’s large scale export to Europe, and Canton in China becomes a center of mass production particularly for export in the 19th century.

Related: How to Furnish Your Modern Home with Antiques

Ming patterns and shapes were followed and reinterpreted in a tighter style, especially in the blue and white palette and likewise with monochromes emulating the finest glazes of the Song Dynasty. Imperial wares are distinguished from those meant for export or provincial market by their highly refined quality and reign marks.

Related: Kintsugi: The Beauty of ‘Golden Scars’

Export wares often exhibit figural scenes or attempt to copy European designs. Some of these are European mythological or literary subjects and often copied from a known design (for example of those by Cornelius Pronk). They are also European in shape - teapots, tureens, plates and dishes.

Modern China (1921 to present day)

Emperor Qing is ousted in 1911 by the Republic of China, and civil war starts in 1927, resuming after World War II. In 1949, Chiang Kai-shek leads the the retreat of the government of the Republic of China to Taiwan also known as the Kuomintang, taking a multitude of imperial artifacts including porcelain to Taipei. Together, these pieces form the majority of the collection of the National Palace Museum. In mainland China, the Cultural Revolution was launched by Mao Zedong in 1966, and relative stability resumes in 1978 under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping.

Related: China’s 7 Most Influential Contemporary Artists

At the more accomplished end of the spectrum, porcelain becomes more delicate and fine, shown off by detailed landscapes and figures. Painted porcelain plaques are sometimes signed and mounted on screens for decoration and an increased production of many decorative items, such as garden seats, jardinieres and large vases. Towards the end of the 20th century, there's a proliferation of deliberate fakes, some of which become ever more convincing and difficult to decipher.

Diana Darwall worked in the Chinese Department at Sotheby's London from 1989 to 2000, where she became an expert and eventually ran the Chinese Export Porcelain and Works of Art sales. Since leaving to bring up her family, Diana has been dealing, collecting and undertaking freelance consultancy work.