The music of the holiday season always includes:

Just hear those sleigh bells jingling, ring, ting, tingling too

Come on, it’s lovely weather for a sleigh ride together with you.

Leroy Anderson’s “Sleigh Ride” has long been one of the most popular pieces of Christmas music in the United States, even though the word “Christmas” is never mentioned in the lyrics.1 According to Steve Metcalf writing in the Hartford Courant, “Sleigh Ride” has also been recorded by performers from a wider range of styles than any other piece in the history of Western music.2

This holiday favorite is only one of many Leroy Anderson compositions, written more than half a century ago, that have become an enduring part of both American concert and popular music.

Anderson’s “Blue Tango,” a sensual and dramatic dance with a sweeping melody, became the first orchestral piece to reach number one on the Billboard popular music chart. It remained at the top of the Hit Parade for twenty-two weeks and was named the top single of 1952. Anderson’s own recording of “Blue Tango” earned him a gold record, a first for an instrumental symphonic recording.3

Anderson also composed the whimsical, hummable, ticktocky “Syncopated Clock.” Written seventy-six years ago, it is still one of the most recognizable tunes today. Musicologist Howard Pollack declared that “Leroy Anderson’s orchestral miniatures, including ‘The Syncopated Clock,’ ‘Sleigh Ride,’ and ‘Blue Tango’ are among the best-known American concert music written after Gershwin’s ‘Rhapsody in Blue’ and Copland’s ‘Appalachian Spring.’”4 Most of us know his music, but few know anything about the man who wrote it.

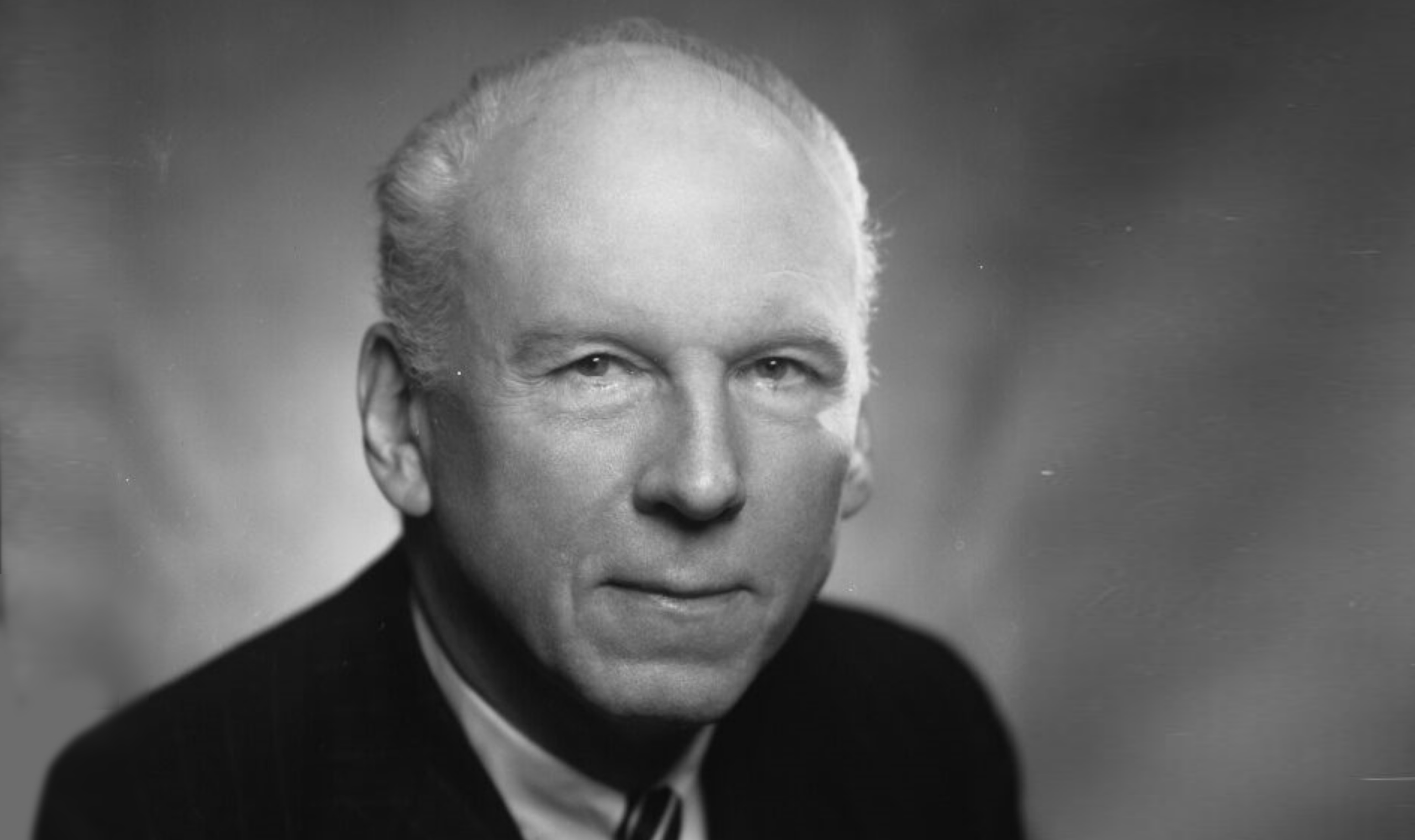

Leroy Anderson was born in 1908 in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the son of two Swedish immigrants. His father was a clerk in the Central Square Post Office, and his mother, who taught Anderson to play the piano when he was five years old, was the organist at the Swedish Mission Church.

Anderson later recalled:

We were a musical family. My father played the mandolin, mother played the guitar and I accompanied them on the piano. Those were happy evenings doing Gilbert and Sullivan, “Drink to Me Only with Thine Eyes,” and all the other songs in The Golden Songbook.

At age eleven, Anderson began piano and music studies at the New England Conservatory of Music, and he composed, orchestrated, and conducted the class song for his high school graduation. In 1925, he entered Harvard University, where he studied musical harmony, counterpoint, canon and fugue, and orchestration and composition. His musical interests included playing double bass, trombone, tuba, and organ as well as arranging and conducting. In 1929, while still a student at Harvard, he also became director of the Harvard University Band.

He graduated magna cum laude in 1929 and was inducted into the academic honor society Phi Beta Kappa; in 1930 he received his master of arts in music, also from Harvard.

Then he nearly made the biggest mistake of his life. Doubting that he had much of a chance for a successful career in music, he decided to study languages instead. He enrolled in grad school, working toward a PhD in German and Scandinavian languages at Harvard. Anderson spoke English and Swedish growing up at home, and he eventually became fluent in Danish, Norwegian, Icelandic, German, French, Italian, and Portuguese.

But he never abandoned music completely. While studying languages for his PhD, he worked as an organist and choir director at the East Milton Congregational Church and conducted and wrote musical arrangements for dance bands around Boston. In 1932 Anderson resumed leading the Harvard University Band, writing witty pieces and doing arrangements for the band that are still held in high regard and played today.

In 1936, his compositions and arrangements for the Harvard band came to the attention of Arthur Fiedler, conductor of the Boston Pops Orchestra. Fiedler asked Anderson for original compositions that he might use in his concerts. In response, Anderson wrote his first work for the Boston Pops, “Jazz Pizzicato,” in 1938. Fiedler wanted to record it, but the piece was just over ninety seconds and thus too short for a three-minute 78 rpm single. Fiedler suggested that Anderson write a companion piece, and he did. It was “Jazz Legato,” which he wrote later that same year. The combined recording went on to become one of Anderson’s signature releases. From then on, Anderson wrote a steady stream of orchestral miniatures, symphonic pieces of about three minutes in length, for the Boston Pops.

In 1942 Anderson joined the United States Army as a private and was assigned to the U.S. Counterintelligence Corps as a translator and interpreter. He attained the rank of captain and, in 1945, he was reassigned to the Pentagon as chief of the Scandinavian Desk of Military Intelligence. In 1945, while still working at the Pentagon, he composed “The Syncopated Clock” and “Promenade.” At the end of the war, he was offered the post of assistant military attaché in Stockholm. He declined. He was now fully committed to a musical career.

When he left the army in 1946, he moved into his mother-in-law’s Woodbury, Connecticut, cottage with his wife, fourteen-month-old daughter, and an upright piano. Anderson said:

During that first summer that we were here, I started “Fiddle Faddle.” I didn’t finish that until the following winter, and “Sleigh Ride” and “Serenata.” And “Sleigh Ride,” I remember, was just an idea because, it was just a pictorial thing, it wasn’t necessarily Christmas music, and it was written during the heat wave.5

He later wrote:

I had felt that the original theme of “Sleigh Ride” was not strong enough to start the number but would make a good middle section. I finally worked out a satisfactory main theme, introduction and coda and finished the orchestra score on February 10, 1948. “Sleigh Ride” was first performed on May 4, 1948 in Symphony Hall, Boston as an extra at a Pops concert conducted by Arthur Fiedler. Lyrics by Mitchell Parish were added in 1950.6

Then Anderson, an army reserve officer, was recalled to active duty in the Korean War. In 1951, during that army stint, he wrote his biggest hit, “Blue Tango.”

Throughout the 1950s, his popularity as a composer was at its height. In February 1951, WCBS-TV in New York City made “The Syncopated Clock” the theme song for The Late Show; and from 1952 to 1961, Anderson’s composition “Plink, Plank, Plunk!” was used as the theme for the CBS panel show I’ve Got a Secret.

From 1950 to 1962, Anderson conducted his own fifty-five-piece orchestra for Decca Records. One biography noted, “Never before had a symphonic composer been given an orchestra to conduct and record freshly written music.”7 With his own orchestra, Anderson premiered and recorded “Belle of the Ball,” “Blue Tango,” “Horse and Buggy,” “Plink, Plank, Plunk!,” “The Typewriter,” and “The Waltzing Cat.”

His Decca recordings were an immense commercial success. Most of these have been rereleased on the MCA label as The Best of Leroy Anderson: Sleigh Ride, and as a two-CD set, The Leroy Anderson Collection.8

In addition to Anderson’s almost two hundred orchestral miniatures, he also wrote a piano concerto and a Broadway musical. In Chicago and Cleveland in 1953, he conducted the only performances during his lifetime of his “Concerto in C Major for Piano and Orchestra.” Unsatisfied with the work, Anderson withdrew it so he could revise the first part. He worked on this concerto for the next twenty years until shortly before he died, but he never completed the changes. His family posthumously published the original concerto without his later changes, which was performed and recorded in 1988.

In 1958, Anderson wrote the music for Goldilocks, a Broadway musical that earned two Tony Awards.9

Other honors Anderson received include a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1976 and election to the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1988. In 1995, Harvard named its new band headquarters after him, and in 2003, Cambridge named the corner near his boyhood home Leroy Anderson Square.10 In 1972, the Boston Pops Orchestra paid tribute to Anderson in a nationally televised PBS concert, and Anderson himself guest conducted one piece. He told his wife, Eleanor, that it was the most important evening of his life.11

Leroy Anderson died on May 18, 1975—yet almost half a century later, his music is still well known and loved by many Americans.12 Why is this so?

Perhaps it is because Anderson taps into and expresses, as no other composer ever did, the joyous, optimistic sense of life of America at its best.

In 2020, Joshua Kosman, music critic of the San Francisco Chronicle, wrote an article titled “Don’t Discount Leroy Anderson’s Undervalued Musical Gems.” Kosman noted:

If Norman Rockwell has a counterpart in the world of orchestral music, it’s the composer Leroy Anderson. Like Rockwell, Anderson found his niche in an underappreciated arena of American popular culture, and infused it with a degree of vibrancy and inventive wit that it rarely enjoyed before or after. . . . Because they’re so short, Anderson’s pieces often tend to cluster in groups . . . [y]et each one is so particular, so distinctive, that—like Rockwell’s Saturday Evening Post covers—they create an entire world in just a few deft creative strokes.13

Composer John Williams, who often performed Anderson’s works when he led the Boston Pops, said “Leroy Anderson is an American original—direct, honest, personal, idiosyncratic, and free of pretension. His music is directed to, and reflective of, the American soul.”14

Anderson’s works do have a distinctly American flavor. “Belle of the Ball,” a whirling, twirling waltz, suggests a grand ballroom but doesn’t really sound Viennese. This may be due to Anderson’s use of horns where Strauss would have used violins. When the “Belle” makes her entrance, a fanfare announces her arrival, and the horns help carry the sweeping melody, giving it an assertive, self-confident strength. “Serenata” begins with and combines a Latin-flamenco rhythm with a freewheeling melody suggestive of 1950s Manhattan sophistication.

Anderson’s lush melodies are skillfully intertwined and orchestrated. His hummable tunes, as Kosman notes, “get into a listener’s memory and lodge there permanently.”15

With the exception of a few slow and thoughtful pieces such as “Forgotten Dreams” and “The First Day of Spring,” most of Anderson’s music is active, vibrant, and alive. The spirited “Bugler’s Holiday” requires dynamic virtuoso performances from three buglers, and “Fiddle Faddle” is a sprightly whirlwind of activity that doesn’t rest for a second.

Leroy Anderson’s music is inventive and witty. The melody of “The Waltzing Cat” expresses feline grace with “meows” from the violins. Anderson used sandpaper as a percussion instrument in “Sandpaper Ballet” and an actual typewriter in “The Typewriter”—a musical composition that has survived long after typewriters became obsolete. Last year, choreographer Bridie Gane created a humorous dance number called “Reception” about two receptionists without any customers at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, trying to cope with the boredom. Gane used “The Syncopated Clock” and “The Typewriter,” substituting computer keyboards for typewriters—and it worked.16

Above all, Leroy Anderson’s music is just plain joyful. YouTube comments on “Bugler’s Holiday” include “This song always makes me happy” and “This tune is just one of the very few that could cure total depression.”17

Although both popular and more traditional orchestral music have become quite sad, angry, and unmelodic since Anderson’s day, the upbeat, optimistic appeal of Anderson’s music remains strong. On April 22, 2020, at the start of the pandemic, a classical music critic of the New York Times wrote an article titled “Leroy Anderson Is the Composer for Now.” He advised, “During our present moment of crisis, Bach provides solace, Beethoven stirs us with resolve and Brahms probes aching emotional ambiguities. But trust me: Leroy Anderson will make you feel better about things.”18

So, if you are happy and seeking confirmation—or striving and seeking inspiration—listen to the joyful American music of Leroy Anderson.

Click To Tweet

You might also like

1. “American Composer Leroy Anderson Wrote ‘Sleigh Ride’ in Woodbury Connecticut,” Leroy Anderson Foundation, http://www.leroyandersonfoundation.org/sleigh_ride.php (accessed November 11, 2021).

2. “Quotations about Leroy Anderson,” Woodbury Music Company, http://leroyanderson.com/accolades.php (accessed November 11, 2021).

3. “Leroy Anderson,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leroy_Anderson; “Leroy Anderson,” PBS, https://www.pbs.org/sleighride/Biography/Bio.htm (accessed November 11, 2021).

4. “Quotations about Leroy Anderson.”

5. “Leroy Anderson on Christmas and Christmas Music,” WTIC Radio, Hartford Connecticut, http://www.pbs.org/sleighride/From_Leroy/xmas_music.htm (accessed November 11, 2021).

6. “The Story of How ‘Sleigh Ride’ Was Written,” Leroy Anderson Foundation, http://www.leroyandersonfoundation.org/sleigh_ride.php (accessed November 11, 2021).

7. “Leroy Anderson,” PBS.

8. You can listen to both albums on YouTube and Spotify.

9. Kathy Warnes, “Leroy Anderson Captures Fun and Feelings in His Music,” History Because It’s Here, https://historybecauseitshere.weebly.com/leroy-anderson-captures-fun-and-feelings-in-his-music.html (accessed November 11, 2021).

10. “Leroy Anderson: Biography,” LeroyAnderson.com, updated November 19, 2020, http://www.leroyanderson.com/biography.php.

11. “Leroy Anderson,” PBS.

12. “Leroy Anderson: An Immigrants’ Son Takes a Sleigh Ride to the Hollywood Walk of Fame,” New England Historical Society, https://www.newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/leroy-anderson-immigrants-son-takes-sleigh-ride-hollywood-walk-fame/ (accessed November 11, 2021).

13. Joshua Kosman, “Don’t Discount Leroy Anderson’s Undervalued Musical Gems,” Datebook, February 5, 2020, https://datebook.sfchronicle.com/music/dont-discount-leroy-andersons-undervalued-musical-gems.

14. “Quotations about Leroy Anderson.”

15. Kosman, “Don’t Discount Leroy Anderson’s Undervalued Musical Gems.”

16. Bridie Gane, “NHT—Reception,” https://vimeo.com/492909781/c37e4063ac (accessed November 11, 2021).

17. Nigel Fowler Sutton, “‘Bugler’s Holiday’ by Leroy Anderson,” YouTube, October 31, 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XHDd0jQxrI0U.

18. Anthony Tomassini, “Not Bach or Beethoven, but Leroy Anderson Is the Composer for Now,” New York Times, April 22, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/22/arts/music/leroy-anderson.html.