Looking into the near future, an anonymous writer in Sydney’s Sun Herald in May 1954 said “the 45s – 7 inch microgroove discs turning at 45 revolutions a minute – holds a position in the Australian record world rather like Cinderella’s. Someday, presumably Prince Charming (in the form of the Australian buying public) will suddenly realise the quality of this disc princess and she will dazzle the world.”

In 1955 two discs were released that dramatically accelerated their popularity. But more on those shortly. This story covers the four years or so it took for the “One Ounce Bombshell” or “Mighty Midget”, as the 45 was dubbed at various times in its early days, to become a central part of music culture in Australian homes.

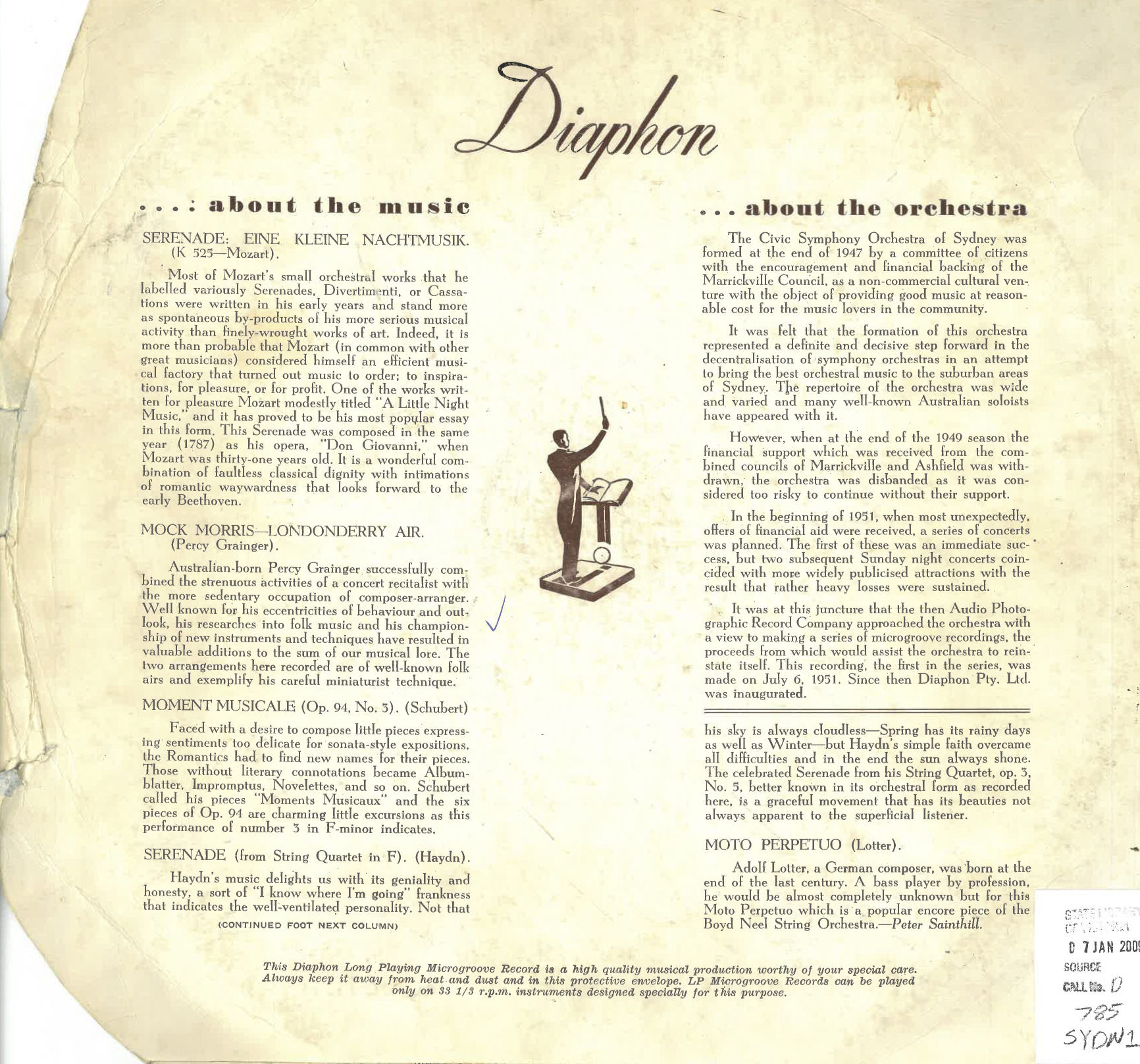

The Australian Record Company and Capitol Records

In early 1951 the Australian Record Company (ARC) was best known as the place where many of the most popular radio programs in the country were produced and recorded. At one time it was producing a greater volume of recorded programs than any other plant in the Southern Hemisphere. In mid 1951 announcements began appearing in press across the country that the ARC had reached an agreement to market and manufacture discs from the U.S label Capitol for Australian record buyers. The first Capitol 78s became available on the 9th August 1951. CT-001 was How High The Moon by Les Paul and Mary Ford.

Battle Of The Speeds

Stories about the ‘Battle of the Speeds’ were not uncommon at the time. In the U.S and Europe all three speeds were available. In Australia the focus was still on the popular 78 rpm format and the emerging 33 1/3 rpm LP market. A story titled Record War Extends, published on 5th August 1951 discussed the ARC agreement and looked ahead to the potential for introducing 7” records saying “prospects of 45 rpm records before Christmas are still doubtful, and will depend on supplies of raw material; but if one local firm adheres to its plans and starts production of 20,000 a week, as threatened, it seems certain that other groups will join in immediately.” Triple speed players (78, 45 and 33 rms) made by Decca were available in October 1951 and units made by Stromberg Carlson were being advertised in November.

Despite these developments, 1952 appears to have passed without any further significant initiatives relating to 45s. It is worth noting that a key marketing aspect of the new LPs across 1952 and 1953 was that they had a greater playing time than standard 78s. This was particularly attractive to the classical record buyers who comrpised biggest market segment at the time. In this light, the smaller 7” with less playing capacity, might have appeared to be a less attractive proposition.

Extended Play and Augmented Play 78 rpm Records

In August 1953 Sydney’s Festival Records, and Germany’s Radiola-Telefunken both announced technological advances that facilitated longer playing times for their 78s. Festival called the new discs Extended Play (EPs) while Radiola announced them as Augmented Play (APs). Festival’s EPs were developed by Robert Iredale who would go on to a long career with the label. The EP allowed for 9 minutes a side on a single 78, which meant 4 songs could fit on one disc without extra cost. Pianist Les Welch released the first Festival 78 EP which featured My One And Only Heart, Say You’re Mine Again, Lay Something On The Bar Beside Your Elbow, and Just Another Polka.

The First 7” 45 rpm Records In Australia

The first 7” 45 rpm records were extended play discs, featured at least four songs, and were marketed by the Australian Record Company on the Capitol label beginning in October 1953. Writing on November 1st, Hugh Bingham said “Capitol appears to have taken a trick in the battle of the speeds with the first 45 EP.” The ARC chose Desert Songs by Gordon MacRae and Lucille Norman as the initial release with the catalogue number CEC-001. The CEC series continued with light classical material from The Indianapolis Symphony Orchestras., the Ballet Theatre Orchestra’ and Leonard Pennario through late 1953 and into 1954. By November ARC had added the CEF line which focussed on jazz recordings. The Goodman Touch by Benny Goodman (CEF-001) was the first in this series and the second 45 rpm disc to be released in Australia. The CEF series expanded over the coming months with additional titles from the likes of Nat ‘King’ Cole and Pee Wee Hunt.

The Greatest Novelty Records Of The Moment

“At last the 45 rpm extended playing records are to hand” wrote a reviewer for The Mirror in Perth on November 7th 1953. They are “lifelike in their reproduction and each side plays for 7 minutes compared with the usual 3 minute playing time of a 10” standard disc.” In December, music writer Gil Walquist discussed the pricing and convenience of the different speeds available and praised the high quality reproductions on 45 are saying they were the “greatest novelty in records at the moment”.

Highlighting their summer broadcasts for 1953/54, 2GB in Sydney announced a new program called The 45 Club. It was presented by Leon Becker, and at the time it was thought to be the first full radio program of featuring only 45rpm microgroove recordings in Australia.

However the 45 didn’t take off right away. Writing on the 13th April 1954 Gil Wahlquist noted that “radio stations in South Australia are not installing three speed machines and that is holding up the development of the 45 rpm market. At some stations, including the ABC said Wahlquist, “the playing of 45 rpm discs is a ‘special’ job, and not for the ordinary shift rostered announcer, who spins the majority of the discs you hear on air.” Wahlquist also writes that Capitol’s policy for issuing 45 rpm is that they don’t duplicate music issued on other speeds. Additionally, he flagged plans by EMI to begin issuing English pressed 45s in the next two or three months. Ultimately he concludes “although it is languishing at the moment, the 45 business is no flash in the pan.”

Nixa Add Classical Titles

Although EMI had been talking about local 7” records in the next few months they were not the next label to issue 45s. Electronic Industries Ltd had been pressing LP records on the Nixa label since late 1952. and on the 1st of May 1953 Perth newspaper the Mirror reported that Nixa was “to enter the 7” 45rpm market in the next two weeks with releases of light classical orchestral pieces.” Sure enough, the first two titles, Strauss Operetta Weiner Blut by the Berlin Civic Opera (UREP 5) and Ponchielli Opera La Giaconda by Professori d’Orchestra La Scala (UREP 1), were reviewed on the 11th May by Brian Moroney. By August 1954 Nixa had issued at least half a dozen 45 rpm discs featuring the likes of the Symphony Orchestra of Radio Leipzig, the Radio Berlin Orchestra, and the La Scala Orchestra of Milan. These were all sourced from the Urania label. Advertisements from the time show Nixa marketing these discs as having 7 minutes of music per side. This appears to make it the second label to begin marketing 45 rpm records in Australia.

The First Nixa E.P Issued In Austraila

EMI/Columbia/HMV Release The First 45rpm Single Play Discs

Ads for the first HMV & Columbia 45 rpm Microgroove records were appearing in the papers by August 1954. While Capitol and Nixa focussed on the extended play format, E.M.I’s initial releases were the earliest 7” single play records to become available in Australia.

Early advertisements emphasised that these were music for the “average record collector” and that they were “NOT extended play”. Music writer Gil Wahlquist featured the first E.M.I singles in a September 1954 article noting that “their surface is superior, they are almost unbreakable, and they are easy to handle, stack, and store.” The singles were available for 6/10 which made them cheaper than the Capitol 7” EPs on the market.

The First Columbia 7″ Issued In Australia

Those available included Josef Locke – My Heart And I (SCMO-101), Benny Goodman and his Orchestra – Temptation Rag (SCMO-102), Ray Martin’s Concert Orchestra – Carnavalito (SCMO-103), Montparnasse – Eddie Calvert (SCMO-104), and I’d Give My Life – Frankie Laine (SCMO-105) on the Columbia label, and Valse Triste – Leopold Stokowski (7RO-101), Merry Wives of Windsor – London Philharmonic Orchestra (7RO-102), and The Stars Were Brightly Shining – Giuseppe di Stefano (7RO-103) on the His Masters Voice (H.M.V) label. In October radio reporter Lesley Morris wrote that E.M.I had announced they were replacing 78s with other speeds in the U.K and would be doing the same in Australia in time. By December E.M.I had decided to add 7” EPs to their catalogue, and did so by issuing titles by acts including Ken Griffin and Duke Ellington. At first, the EPs were imported from the U.K before local production began later in 1955. This explains why early reviews use the U.K catalogue numbers. For example this review on 7th December 1954 cites the Duke Ellington EP available as being SEG-7503 whereas the local pressing Duke Ellington – Hawk Tales eventually carried the catalogue number SEGO-7503. In February 1955 E.M.I announced that it would release as average of eighteen discs a week in that year and that three of those would be 7” 45rpm records.

One Of The First E.Ps Issued By Columbia (E.M.I) in Australia

Fixing The Spindle Holes

Over the ten months since the introduction of the 7” it appears that Australian record buyers had been frustrated by different sized spindle holes in their records. LPs and 78s had a small hole while 45s had larger holes. As early as October 1953, A.R.C were marketing “a dingus called ‘a spider’ which enables the [7”] discs to be played on a normal turntable”.

April 1954

August 1954

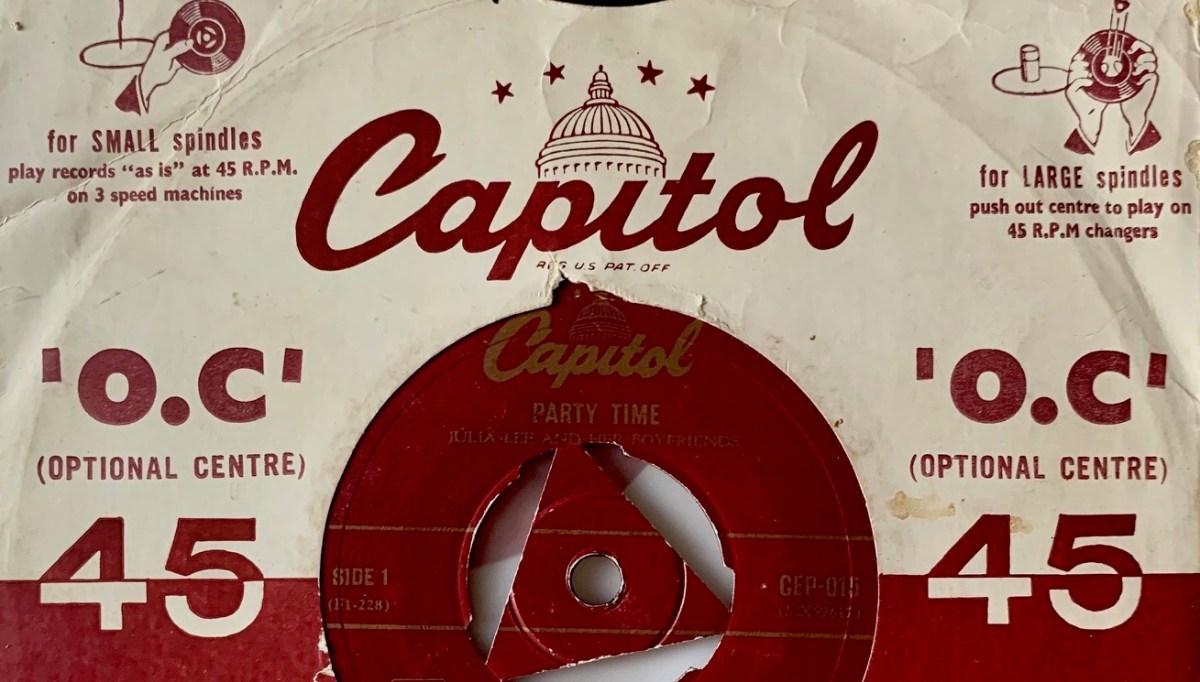

Writing in the The Sun on 5th August 1954, Vox Pop said “part of the reason for slow sales so far in the 45 discs has been the finicky business of fitting spiders into the 1 ½ in centres to fit them on a standard spindle.” On the same date, as E.M.I launched their 7” single, the ARC introduced the “Optional Centre” or O.C for it’s Capitol 45s. The O.S discs gave the option of playing them on a small spindle “or (by pressing out the centre piece) on the larger one found only on special 45 rpm players.” Praising their local development, George Hope in the Daily Telegraph on 8th August 1954, wrote that production of 45s has been “stepped up.”

Julia Lee – Party Time (CEP-015) – One of the first Capitol discs to be marketed with the Optional Centre

Among the first to hit the stores were Julia Lee & Her Boyfriends – Party Time (CEP-015) Dixieland Detour by Pee Wee Hunt (CEP-022), Stan Kenton Classics (CEP-023) and Cocktail Time with the Ernie Felice Quartet (CEP-024). Subsequently, September advertisements for the first E.M.I singles also made mention of their ‘new optional centre’ as well.

Festival Records Join The 45 Market

Rear sleeve for Barry Frank Festival EP XP45-627 (1955)

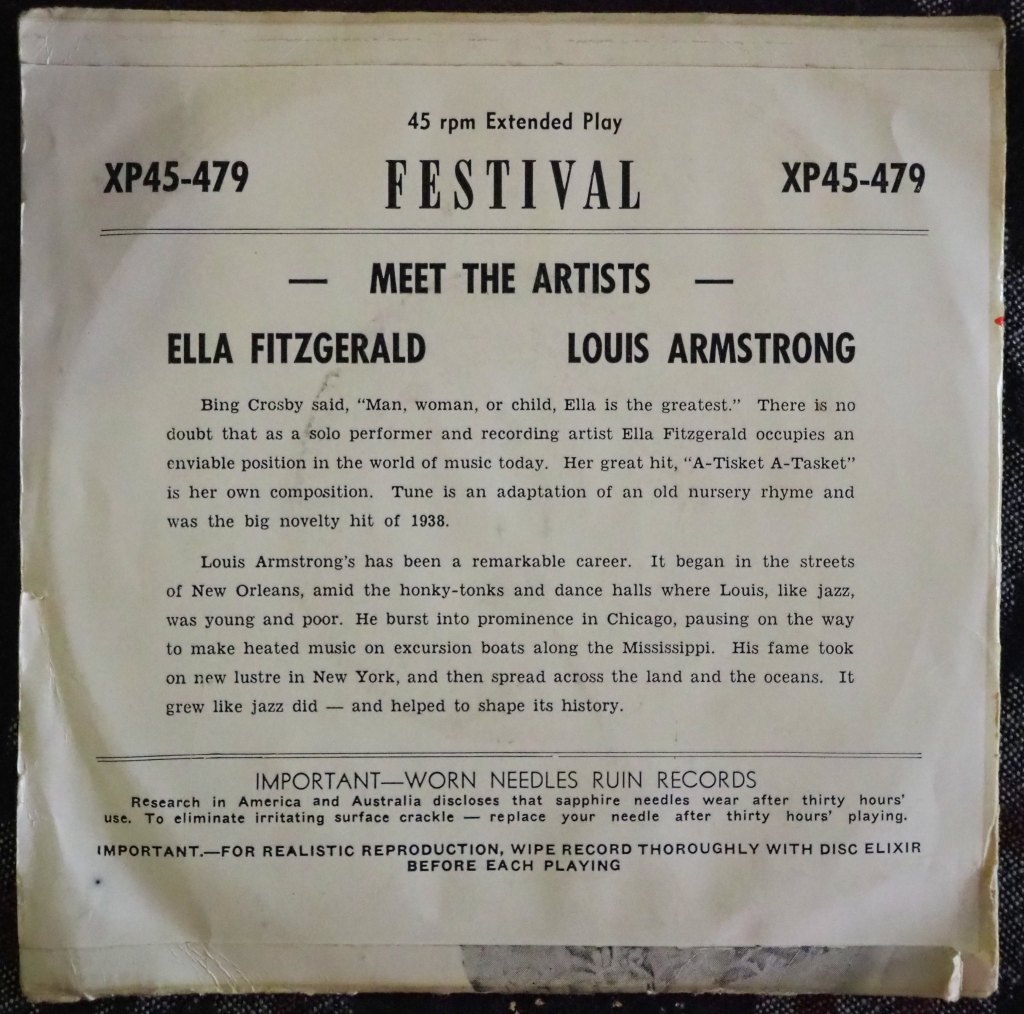

Up until October 1954 Festival Records had continued to rely on their innovative 78rpm E.Ps. However, on 24th November Festival announced their first release 45 rpm E.P which featured Ella Fitzgerald with Louis Armstrong and Delta Rhythm Boys (XP-45-479). Where there had been quality control issues with early Festival LPs and 78rpm E.Ps, it seems they hit the ground running with their 45 E.Ps. On the 18th December 1954 Harold Tidemann reviewed the Fitzgerald/Armstrong E.P saying that the reproduction it offered was “first class”.

The First 45 E.P Issued By Festival Records

Early advertisements pointed to future 45rpm titles by Alfred Drake & Mimie Benzell (XP45-451/2), Frank Luther (XP45-476), and Pearl Bailey (XP-45-447) as ones to watch out for. These appear to have been in stores by January 1955.

By Autumn 1955 45rpm records had been around for almost 18 months and yet no company had issued one by an Australian artist. Festival were the first to do so. As had been the case with the first Festival release in 1952, the first 7” featured the label’s music director Les Welch. Les Welch and his Orchestra (XP45-624) and Les Welch and His Boogie Woogie Quartette (XP45-626) were the initial offerings. They were soon followed by Tess & Flip Carbine – Wagon Wheels (XP45-633) in May 1955, and the Gus Merzi Quintette – Dizzy Fingers (XP45-656) in June. All four were extended play discs.

One Of The First 45s To Feature An Australian Act

First Australian Country 7″ – May 1955

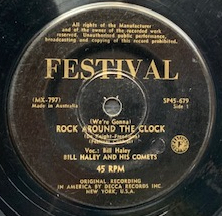

July 1955 marked a turning point for the the 45rpm in Australia when Festival issued two of its first 7” singles: Bill Haley and his Comets – Rock Around The Clock (XP45-679) and Darryl Stewart – A Man Called Peter (XP45-684). By the years end these singles would be two of the biggest hits of 1955.

Interestingly, the songs were featured in two very different films which proved to be among the most popular with Australian audiences over the next 6 months, and it is likely this also played an important part in their recognition. Rock Around The Clock Was featured in an expose of rebellious youth culture called Blackboard Jungle, while A Man Called Peter was the title song for a film about a Scottish man who received a calling from God and became Chaplain of the U.S senate.

Rock Around The Clock

While it’s well known as a classic of rock and roll today, Rock Around The Clock didn’t grab everyone’s attention upon its release. Presenting the A.B.C’s jazz program Tempo Of The Times in July 1955, Alan Saunders played the records with the back announcement ‘That recording was played by Bill Haley and his Comets, and it will be all right with me if they don’t come around for another 70 years.” Others got it right away though and two weeks later Geoff Brooke, writing in his On The Grapevine” column in the Argus, reported on the new American popular music trend of ‘rhythm and blues’ which has the “whole band swinging a series of repetitious phrases, while a tenor saxophone honks away wildly over them.” Brooke cited Rock Around The Clock as a good example of the style, before sharing that the single was currently popular and that Colin Canning at Loel’s Rhythm Corner in Melbourne had reported selling 42 copies in just one hour the previous week. By the 20th August 1955 stories were being published that no single before Rock Around The Clock had sold so proficiently. A review in the Argus stated that the single has already sold 10,000 copies in Melbourne alone.

Rock Around The Clock Sample Record

First Pressing of Rock Around The Clock (note: publisher is Festival Control)

A noteworthy aspect of Rock Around the Clock is the different ways in which people tried to describe it. On 13th August 1955, Bill Patey wrote about the “Rock Around The Clock brand of jazz” that should have appeared in the film The Wild One (as opposed to the west coast jazz it utilised). A later review by Patey described it as “another variation on the hackneyed Shot Gun Boogie chord progression”, while another August 1955 newspaper column recounted a call to the Festival offices by a woman who was inquiring whether or not it could be considered a lullaby. By September, columnist Geoff Brooke was identifying it as rhythm and blues and predicting that it wouldn’t last long as a popular form of music.

Of course it did last and ultimately Rock Around The Clock sold over 140,000 copies and spent six weeks at number one according the Kent Music Report.

A Man Called Peter

A Man Called Peter premiered in Australian cinemas in July 1955. It proved to be a very popular film in the second half of 1955 and into 1956. When it opened at the Regent in Melbourne in January 1956, Hoyts offered a money back guarantee to film goers and it was claimed that this was the first time such an offer had been made.

The first hit 7″ by an Australian act in 1955

The theme song was cut in the U.S by vocalist Bill Farrell, whose version was being marketed in Australia as a 78rpm in early August 1955 on Esquire-Mercury. However, as they had often done before, Festival decided to cut a local version with vocalist Daryl Stewart. Les Welch did the arrangement, Wilbur Kentwell played organ and he was accompanied by trumpeter Dick McNally. By October 1955 it was listed as a best seller.

The Kent Chart listed the song as one of the biggest hits of the year and it appears to have been a popular choice of song for many amateur singers at functions at the end of the year.

More Local Labels Launch 45s

As sales for these and other popular releases continued, it was becoming increasingly obvious that the record buying public were pleased with the 45rpm format, either as extended or single plays. This resulted in more labels issuing their own 7″ records.

Electronic Industries Ltd, who were already had light classical 45s on Nixa, began issuing popular recordings on Mercury in March/April, featuring artists like Jan August and Patti Page, and then jazz cuts on Clef in August, with the Gene Krupa Sextet – Payin’ Them Dues Blues (CL-001) as the initial release.

Early Jan August E.P On The Mercury Label

Debut Single For The Clef Label

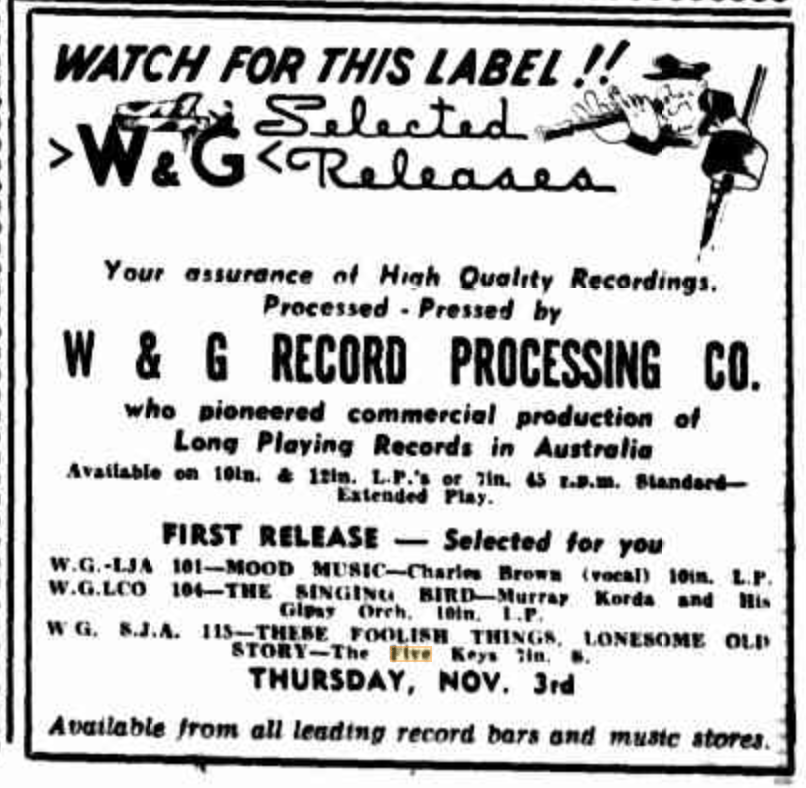

Melbourne’s W&G label were advertising their first 45 in October, offering The Five Keys – Lonesome Old Story (WG-SJA-115). By early 1956 they’d added E.Ps including Maxwell Davis – And His Tenor Sax (WG-EBA 107).

October 1955 Ad For W&G

Early W&G E.P from Maxwell Davis

To cap the big year they had enjoyed with 7” records, In December Festival issued Ella Fitzgerald – Songs In A Mellow Mood (XP45-693/3) which was a triple 45 package.

The 45 Really Takes Off

The Australian Record Company (A.R.C) launched the Coronet label in January 1956. As they had done previously with Capitol, their focus was initially on 45rpm extended play releases. Songs From Guys And Dolls (KEP-001) and Cha Cha – Belmonte And His Orchestra (KEP-003) were among the first. Their single releases stayed in the 78 format until later in 1956 when they also began issuing 7” singles on the label. In April 1956 ARC also began issuing 7” records on its Pacific label which featured Australian artists. The first release was the extended play Accordion Time by the Camilleri Quartet (PEP-001).

The first Coronet 7″

Early Coronet 7″ E.P

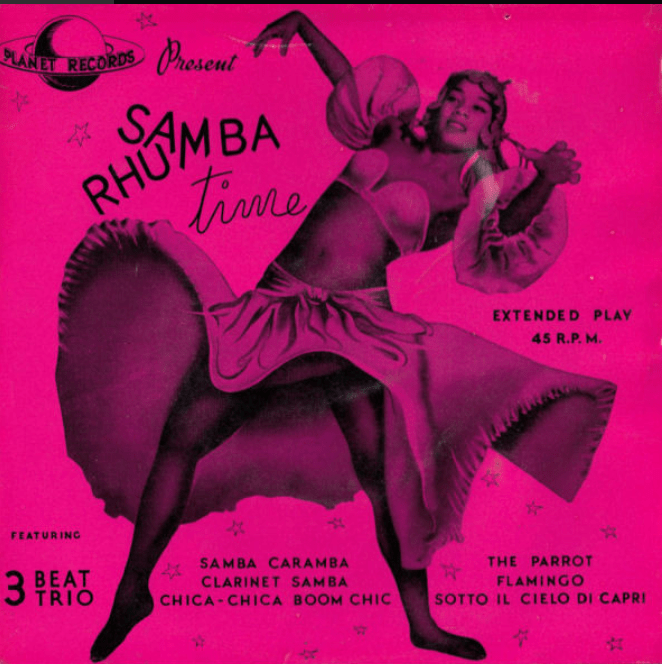

Further Australian innovation with the 45 was announced by Planet Records in February 1956 as they began to promote their first extended play discs with six songs. Bob Crawford and Marcus Herman had developed a ‘secret process – claimed to be unique in the world’ for putting three tracks on each side of a 7”. The opening release to feature the technological advance was Samba-Rhumba Time – The Three Beats (PZ-001).

The First Planet EP Featuring 6 Tracks

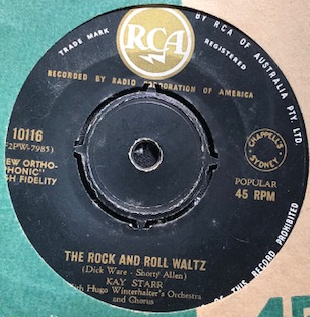

Perhaps the last, but by no means least, notable entrant into the 7” market was Amalgamated Wireless of Australia (A.W.A) who secured the exclusive rights to distribute the American R.C.A label. R.C.A had signed Elvis Presley in November of 1955 and already had established stars like Mario Lanza, Perry Como and Eddie Fisher on their books. In late May A.W.A began to issue 45s with initial releases including Eddie Fisher – Dungaree Doll (10115) & Kay Starr – Rock ‘n Roll Waltz (10116). Heartbreak Hotel, Presley’s first 45 release in Australia followed in July. Despite reviewer Bill Patey describing it as “a grotesque grasp-and-groan opus” the single represented the first of many hits for Presley over the decades that followed. Success that helped cement the 7” 45rpm in the hearts of record buyers across the country.

Early RCA 45s

I’ve tried to use as many resources as I could find to inform this story. Thanks to those collectors (Martin, Kevin, Clem & David among others) who helped me with a couple of the images I was chasing. If you have additional information that would improve it’s scope or accuracy then please leave a comment or get in touch via the contact page. It’s always great to hear from fellow collectors.

If you enjoyed reading then please share with your friends and sign up for email alerts from Sonic Archaeology (back at the top of this page) whenever something new is published.