By Stephen Basdeo, a writer and historian based in Leeds.

The popular song Mack the Knife was based upon the story of an eighteenth-century highwayman named Captain Macheath. This post traces the literary life of this fictional character.

Most people, at some point in their lives, will have heard the song Mack the Knife, which has been covered by a wide range of singers including Louis Armstrong (1901–71), my personal favourite, Bobby Darin (1936–73), Frank Sinatra (1915–98), and Roger Daltrey (1944–). Few people will realise, however, that the song is based upon the story of a fictional eighteenth-century highwayman named Captain Macheath, who first appeared in John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera (1727) and whose story was subsequently reimagined in Bertold Brecht’s The Three-Penny Opera (1928).

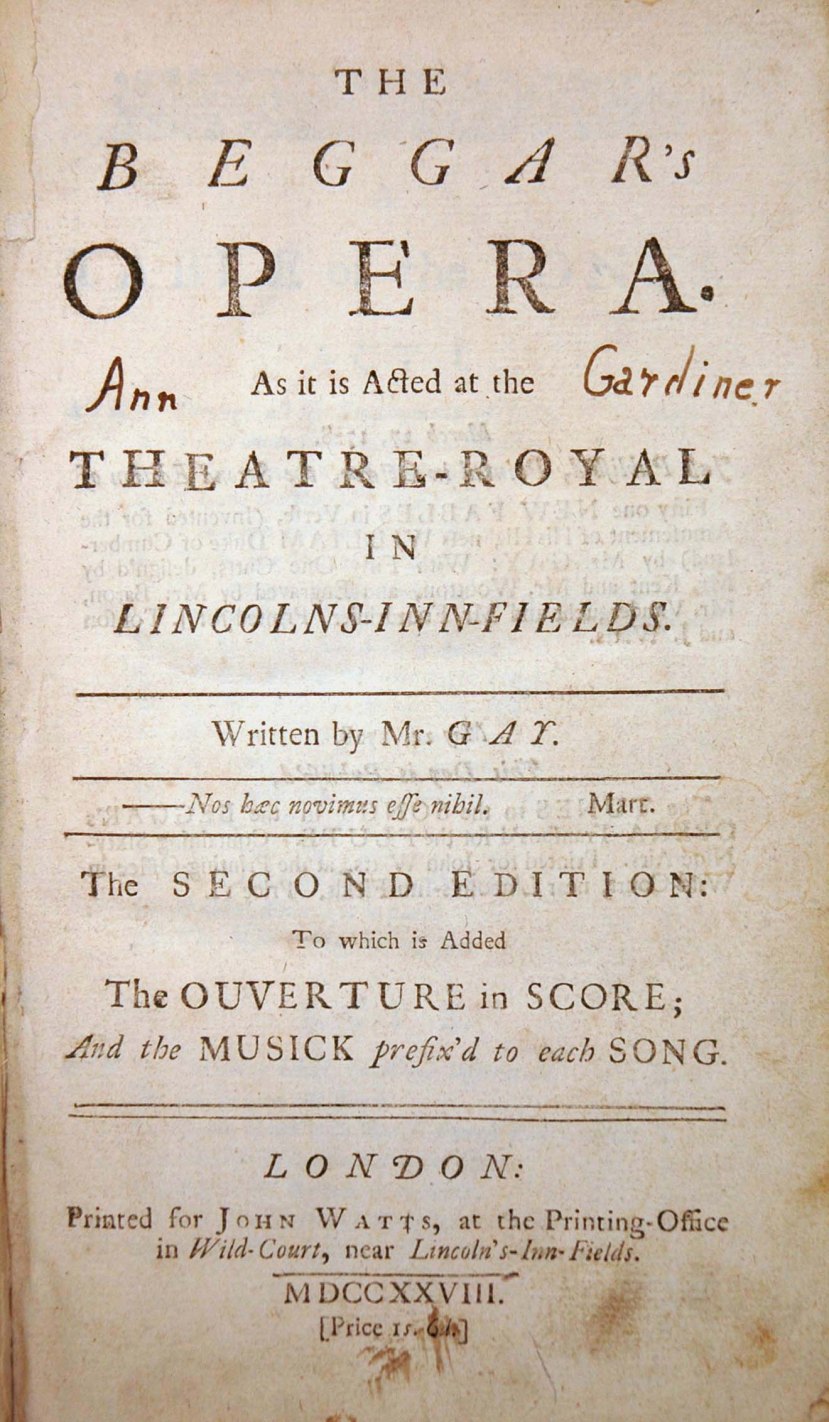

John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera (1728)

Gay’s opera was essentially the first ‘jukebox musical’: it took the tunes of contemporary popular folk songs, changed their lyrics, and inserted them into the narrative. It tells the story of a womanising highwayman, Macheath, based upon the real-life thief, Jack Sheppard (1702–24), who has a romance with the daughter of the thief taker, Peachum. The latter is a character based upon Sheppard’s nemesis, Jonathan Wild (c. 1688–1725). As thief taker, Peachum controls all the crime in London in his capacity as the main law-enforcer, and has the power of life and death over his criminals. He takes exception to the proposed marriage between Macheath and his daughter and resolves to have him hanged. What follows is a comical tale of encounters with sex workers, escapes from gaol, until finally he is taken to be hanged. Instead of being hanged, however, the playwright steps on to the stage and proclaims a reprieve at the last moment, saving the heroic highwayman from the gallows.

The play did much to cement the image of the heroic highwayman in public consciousness with contemporary audiences, which built upon previous portrayals of some robbers as noble and generous in criminal biographies such as Alexander Smith’s History of the Highwaymen (1714) and Charles Johnson’s History of the Highwaymen (1734).[i] In turn, later highwaymen such as James Maclaine (1724–50) fashioned themselves as modern-day Macheaths in order to curry favour with the public. In his play, Gay had a wider point to make, however: he wanted to criticise the government; the leading ministers of state were no better than the corrupt thief takers who patrolled London’s streets and who, while they prosecuted certain small-scale, petty criminals, left larger crimes unpunished. Thus we see Peachum in the opening scene of The Beggar’s Opera singing:

Through all the employments of life

Each neighbour abuses his brother;

Whore and rogue they call husband and wife,

All professions be-rogue one another.

The priest calls the lawyer a cheat,

The lawyer beknaves the Divine,

And the statesman because he’s so great,

Thinks his trade as honest as mine.[ii]

He then proceeds to say

A lawyer is an honest employment, so is mine. Like me too he acts in a double capacity, both against rogues and for ‘em; for ‘tis fitting that we should protect and encourage cheats, since we live by ‘em.[iii]

A particular target of Gay’s attacks in The Beggar’s Opera was the Prime Minister, Sir Robert Walpole (1676–1745). Widely viewed as corrupt, even though nobody ever managed to trace any particular frauds or embezzlements to him, to satirists in the eighteenth century he represented all that was wrong with the ruling aristocratic oligarchy.

(Portrayals of Captain Macheath/Mack the Knife through the Ages)

During the Victorian period, with the rise of the penny dreadful publishing industry, tales of highwaymen became immensely popular with both adults and youths of the lower middle and working classes. Dick Turpin (1705–39) appeared regularly in the columns of these cheap magazines, as did older highwaymen such as Robin Hood and the afore-mentioned Jack Sheppard. The actual stories differed little from other contemporary tales of highwaymen, being mostly full of daring adventures, escapes from the police, and the rescue of young maidens from aristocratic villains. Pierce Egan (1814–80), an author about whom I have written a lot on this website, authored Captain Macheath: The Highwayman of a Century Since (1840). Later anonymously-written penny dreadfuls include a long running serial in the magazine Tales of Highwaymen (1865–66), as well as Captain Macheath: The Prince of the Highway (1892), which is a virtual plagiarism of Egan’s earlier novel.

The song Mack the Knife does not appear in Gay’s opera, but appeared Brecht’s Three-Penny Opera. While in Gay’s earlier play, Macheath is a jovial and relatively good-natured fellow who flinches from using violence, Brecht gives us a Macheath, or a ‘Mack the Knife’ who, it is hinted, has a darker side to his character. This comes through most clearly in the song entitled Die Moritat von Mackie Messer, sung usually at the beginning of the play, which is the song we all know as Mack the Knife:

Oh, the shark has pretty teeth, dear

And it shows them pearly white

But the knife that Macheath carries,

No one knows where it may be.[iv]

The song then gives us a litany of some of the quite brutal crimes attributed to Macheath/Mack the Knife:

On a blue and blamy Sunday

On the Strand a man has lost his life.

A man darts around the corner,

People call him Mack the Knife.

And Schmul Meier is still missing,

One more wealthy man removed,

Somehow Mackie has his money,

Yet nothing can be proved.

Jenny Towler was discovered,

With a knife stuck in her chest,

Mackie strolls along the dockside,

Knows no more than all the rest.

Seven children and an old man,

Burned alive in old Soho

In the crowd stands Mack the Knife

Who’s not asked and doesn’t know.

And the widow not yet twenty

Only her name could she say,

Defiled one night as she lay sleeping

Mackie what price did you pay?[v]

Murder, arson, and rape: all of these crimes are attributed to Macheath; even though he is the hero of the tale, he is certainly not as noble and gentlemanly as the Macheath of Gay’s story. The story of the play is essentially the same as The Beggar’s Opera, although it is set in Victorian London instead of Georgian London as Gay’s play was: Mack the Knife marries Polly Peachum, to the chagrin of her father Peachum who is an underworld crime lord; in concert with the Chief of Police, Peachum convinces the policeman to gather enough evidence to hang Mack. Eventually Mack is arrested and is taken to be hanged, but at the last minute a pardon arrives from Queen Victoria for him. He is released and is soon elevated to a Baronetcy, the implication being that he can now steal from people legally because he is a member of the aristocracy. Through this means, Brecht, a socialist, offers a critique of the corruption endemic in the modern capitalist city in which thieves are no better than the elites, which is a similar argument to that made by Gay almost two centuries before.

Later singers, such as the ones I pointed out in the introduction, adapted Brecht’s Moritat and gave it the title of Mack the Knife. We see a slight return in these later songs to a friendlier portrayal of Macheath, such as that contained in the Bobby Darin lyrics:

Oh, the shark, babe, has such teeth, dear

And it shows them pearly white

Just a jackknife has old MacHeath, babe

And he keeps it, ah, out of sight.

Ya know when that shark bites with his teeth, babe

Scarlet billows start to spread

Fancy gloves, oh, wears old MacHeath, babe

So there’s never, never a trace of red.

Now on the sidewalk, huh, huh, whoo sunny morning, un huh

Lies a body just oozin’ life, eek

And someone’s sneakin’ ’round the corner

Could that someone be Mack the Knife?

There’s a tugboat, huh, huh, down by the river don’tcha know

Where a cement bag’s just a’drooppin’ on down

Oh, that cement is for, just for the weight, dear

Five’ll get ya ten old Macky’s back in town

Now d’ja hear ’bout Louie Miller? He disappeared, babe

After drawin’ out all his hard-earned cash

And now MacHeath spends just like a sailor

Could it be our boy’s done somethin’ rash?

Now Jenny Diver, ho, ho, yeah, Sukey Tawdry

Ooh, Miss Lotte Lenya and old Lucy Brown

Oh, that line forms on the right, babe

Now that Macky’s back in town.

I said Jenny Diver, whoa, Sukey Tawdry

Look out to Miss Lotte Lenya and old Lucy Brown

Yes, that line forms on the right, babe

Now that Macky’s back in town

Look out, old Macky’s back

It appears that there are still heavy penalties for those who cross his path, but at least he does not rape women or burn whole families alive in their houses.

For those interested in seeing original versions of The Three-Penny Opera, see the following youtuve videos:

And the Roger Daltrey version of the movie can be found here:

References

[i] For a detailed and scholarly discussion of highwaymen and masculinity see the following: Erin Mackie, Rakes, Highwaymen, and Pirates: The Making of the Modern Gentleman in the Eighteenth Century (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009). For further reading on The Beggar’s Opera (1728) see the following: Lucy Moore, The Thieves’ Opera (London: Penguin, 1997).

[ii] John Gay, The Beggar’s Opera, 3rd Edn (London: J. Watts, 1729), p. 1.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Translated approximately from the original German.

[v] Bertolt Brecht, The Three-Penny Opera (1928).

Categories: 18th century, 19th Century, 20th Century, Alexander Smith, ballads, bandits, Bobby Darin, crime, Crime History, crime literature, Criminal Biography, Criminals, Film, folk ballads, Folk Music, Frank Sinatra, highway robbery, Highwayman, highwaymen, History, Jack Sheppard, James Maclean, Louis Armstrong, Mack the Knife, murder, musicals, Organised Crime, Outlaw, Outlaws, penny blood, penny dreadful, Pierce Egan, Robert Walpole, Roger Daltrey, Socialism, The Beggar's Opera, Underworld

Thanks for the history!

Ther us an echo of “A lawyer is an honest employment, so is mine. Like me too he acts in a double capacity, both against rogues and for ‘em; for ‘tis fitting that we should protect and encourage cheats, since we live by ‘em.” in Omar’s “I got the shotgun, you got the briefcase;It’s all in the game”, speaking of Robun Hood figures https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oYj7q_by_2E