After a long friendship with Michael Jackson, a torrid marriage with Liza Minnelli and eating a kangaroo’s testicle in the jungle, David Gest has become a soul music impresario, and once a year he tours the UK with his Legends Of Soul package. This year’s offering included Candi Staton, Sheila Ferguson (Three Degrees) and Gwen Dickey (Rose Royce). At the bottom of the bill was the 10th act, Little Anthony. It had to be that way, as Little Anthony had only once made the UK Top 50 (Better Use Your Head, making a belated chart entry in 1976 after Northern soul success). But it was astonishing that Little Anthony was on the bill at all. How often do we see the mainstays of the doo-wop era in the UK? Hardly ever.

In any of its many combinations, Legends Of Soul is a great night out and when I caught the show at the Liverpool Philharmonic Hall, my only complaint was that too many singers encouraged audience participation. I want to hear Sheila Ferguson sing When Will I See You Again, not the man next to me. Similarly, I don’t want Candi Staton to hold X Factor-styled auditions for You Got The Love when she can sing it perfectly well on her own. Fortunately, Little Anthony just sang his songs – Tears On My Pillow and Goin’ Out Of My Head – with a few little dance steps that he might have done with The Imperials, and it was sublime. David Gest said that Little Anthony had been Michael Jackson’s favourite singer, and it was easy to understand why.

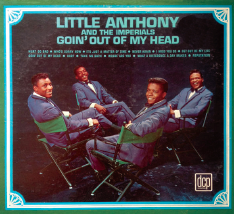

Anthony Gourdine was born in Brooklyn on 8 January 1941. As we shook hands, he said, “Don’t I look good for 39?” In fact, he looks great for 73 and speaks in a high-pitched voice that is both very pleasant and musical. What’s more, he is not that little – 5ft 8in. With The Imperials, Little Anthony won a gold disc for Tears On My Pillow in 1958 and their other major hits were Goin’ Out Of My Head (1964) and Hurt So Bad (1965). And let’s not forget Shimmy, Shimmy, Ko-Ko-Bop (1960)… though he rather wishes you would.

Did you have a musical background?

Oh yes, my mom was a gospel singer and she sang with her sisters in the Nazareth Baptist Gospel Singers in churches around New York and Buffalo. My father played alto and tenor sax with one of the big bands of the 40s, the Buddy Johnson orchestra. I was raised around music and I grew up listening to Ella Fitzgerald and Nat ‘King’ Cole, so I wouldn’t pick any other era. My mom said I was singing when I was three years old. I was singing the pop songs that I heard on the radio – Georgia Gibbs, Patti Page, The Four Aces. I was latching onto the blues: Muddy Waters, Uncle BB – that’s what I call BB King; all these cats playing Delta music.

And then rock’n’roll came along.

The transition really began in 1951 in New York City. There was a radio station that played rhythm and blues, WWRL, and they had a disc jockey called Dr Jive. Tommy Smalls was his real name. Before him, the biggest group had been The Ink Spots, but they sang pop. Now you had Sonny Til & The Orioles, The Clovers and The Crows. There was something special about them – it was the blues but it wasn’t the blues. There was this great backbeat that made you want to dance. It was rhythm and blues.

Some writers nominate Gee by The Crows as the first rock’n’roll record.

I would agree. That was the first rock’n’roll record and Earth Angel by The Penguins came a little bit later. It was a musical revolution as [African-American New York DJ] Tommy Smalls was getting white audiences listening to a black station. Then in 1953, there was this young white disc jockey out of Cleveland who called himself Moondog – his name was Alan Freed. Once that caught on, it became national music. Many of the segregationists called it race music and hated it, but the music was bringing the races together.

Did you get see these groups live?

Yes, The Apollo in Harlem had been a jazz theatre but it made a transition into this new music. My aunts would take me to The Apollo and they had package shows so I might see The Crows and The Diablos on the same bill.

Did you have favourites?

I was blown away by it all, but The Flamingos blew my mind when they came out in 1953. They sang Golden Teardrops, which was so beautiful. They had great harmonies, the best, and it was like they were from another planet.

How did you get started?

I was at the Boys High School in Brooklyn and I met William Dockerty, William Delk and a couple of other people. They were singing in the lunch room and I started singing with them. That led to a group called The Duponts. I didn’t know at the time that I had a unique voice but they would always make me the leader and they did the background. Paul Winley heard us; his brother was in the Clovers, and he convinced us to make a record for his own Winley label. We did a song called You and it was a local hit in the Tri-state area, but we weren’t really going anywhere.

I was with The Duponts for a while when my neighbour Clarence Collins, who lived across the way from me in Fort Green Project, heard us sing. His group was called The Chesters, and he said, “We got something going, but we need a lead singer.” He knew Richard Barrett, who was the A&R man for the Gone and End labels. Richard had told Clarence, “When you’ve got a lead singer, let me know.” The Dubs and The Isley Brothers were on Gone, and Richard Barrett had discovered Frankie Lymon & The Teenagers. We got the subway train to 1650 Broadway and did an audition.

One of The Chesters, Ernest Wright, had written a song, Two People In The World, so we sang that. I used to love Earl Wilson, who did The Closer You Are with The Channels. There was a great tenor thing that he did in there and so I did something like that. When Richard Barrett heard us, he immediately told George Goldner, who was the President of End and Gone. He said, “I think we got another Frankie Lymon.” They told us to come back at six o’clock with our parents and we would sign a record contract.

Two People In The World was a great B-side, but the A-side was Tears On My Pillow.

That was down to George Goldner. We hadn’t worked very much on the song when we did it, but I can hear a melody and know what to do with it. The guys did the background, which is just a variation on Earth Angel by the Penguins. We did a few notes and Mr Goldner said to me, “Can you sing how you talk?”, which was more high-pitched. He also said, “You know how Nat ‘King’ Cole pronounces his words? He says every word very clearly. Can you do it like that?” That’s what I did. One of the words is “Twas” – that’s very British! When we did the song like that, we could sense that something was going to happen. Richard Barrett came out of the booth and said, “That’s gonna be a smash!”

Was the plan to remain as The Chesters?

No, because Mr Goldner didn’t like the name. Their PR man, Lou Galley, saw a Chrysler Imperial go by and said, “What about the Imperials?” The original label just said “The Imperials”, and Imperial margarine had complained, but it didn’t matter. Alan Freed had played the record on air and said, “Well, he sounds like a little guy, let’s call him Little Anthony,” and so they changed the label to “Little Anthony & The Imperials”. I was a skinny little kid and the girls would squeal when I opened my mouth, so I knew I had something that made them scream.

Tears On My Pillow won you a gold record, but was it difficult to follow it up?

That was Richard Barrett’s job. Two young songwriters, Neil Sedaka and Howard Greenfield, had written a song for us, The Diary. I liked that song and it seemed to fit me very well. George Goldner was going to the UK to arrange some distribution for his records and he told Richard to put it out. Richard didn’t want to miss the opportunity of writing a hit song for us, so he put out his own song, So Much, but I didn’t care for it. Neil Sedaka wasn’t very happy about that and RCA released his own version. When George Goldner got back, he put The Diary out as quickly as he could but Neil Sedaka was already in the charts – it was his first hit single.

The guy in the song deserves to have things going wrong for him if he’s looking in his girlfriend’s diary!

Yeah, boys shouldn’t look in diaries, should they? [Sings] “How I’d like to look into that little book”. He was only fantasising. He didn’t have the nerve to look, but he’d sure like to know if she really liked him. It’s a good song.

There’s a single, I’m Alright, that wasn’t a big hit but it’s a great gospel rave-up.

I was raised in the church like most black performers. I knew Sam Cooke when he was with The Soul Stirrers. I saw him and liked him and he knew that I wanted to sing. One day I was fooling around with a gospel tune, I’m Alright, and we had a good beat in there. We went to The Apollo and I had a hunch that we should try this. We rehearsed it with Reuben Phillips’ orchestra and the place went bonkers. I was singing like Jackie Wilson and the girls were loving it. George Goldner said, “You don’t have a bridge in there, but this could be a hit. Why don’t you ask Sam Cooke to help you finish the song?” That’s what I did, and his name’s on the label. A few months later the Isley Brothers did Shout, which is that same gospel beat, but lots of bands did stuff like us after they’d seen us.

I loved Shimmy, Shimmy, Ko-Ko-Bop.

That did okay. It was a most unusual song but I didn’t like it at all. I was a crooner and I didn’t want to do novelties. George had a hunch that the kids would love it. When we did a show for the first Bush administration, Joint Chief Of Staff Richard Myers said, “I just loved that song.” Some groups were famous for novelty songs, but we wanted to sing standards. We did an album of Sinatra’s tunes, Shades Of The 40s, and George was happy with that as he believed I could be a young black Sinatra. David Ruffin of The Temptations loved that LP. He said everybody was looking to see what we were doing.

How do you feel about that album today?

I was too young to be doing that! Sinatra had a much better command of the lyrics than I had – he was the greatest cat when it came to interpreting a lyric. I did them the way I saw them and the album was artistically acclaimed. We were taking a chance and the young audience might have thought, “Why are they going away from things that we like?” Today it’s normal for somebody to record an album of standards, but back then it was unusual.

Other groups tried to do standards and The Flamingos did I Only Have Eyes For You, which was great, but look at The Marcels – they only did Blue Moon in the way that they did their other songs. The Marcels lived in that Rama Lama Ding Dong, Ba-Ba-Ba-Barbara Ann world and we didn’t. We did pop songs with a backbeat like Tears On My Pillow and we were really on that island by ourselves.

You left the group in 1961, then you returned to the fold.

I left in 1961 because I wanted to act because I’d been a child actor and I wanted to go back to the theatre. That was short-lived, just a couple of years but there were no arguments with The Imperials. It wasn’t really a breakup and we still hung around.

Ernest Martinelli who became our manager asked me to get the guys together as a major nightclub in Brooklyn wanted to have Little Anthony & The Imperials. We got back together to do that and then we didn’t leave. We stayed together all the way up to 1971. We’ve had so many cats in The Imperials since then.

In the early 60s, you started to record songs by Teddy Randazzo.

Well, I’d known Teddy back when I was with The Duponts. He was with The Three Chuckles then. We did a show at the New York Paramount for Alan Freed in February 1957 and Teddy said to me, “One day, kid, we are going to work together. You’re going to be my voice.”

At the end of 1963, Ernest met Teddy in the street, and Teddy invited us to discuss things with him and the arranger Don Costa. We had a good meeting and it became one of the greatest collaborations in show business. Don Costa would tell me to listen to Ella Fitzgerald, Frank Sinatra and Tony Bennett. He said, “See how they control the lyric, they know what to do with it. You can have that quality too and it’s my job to get it out of you.”

Teddy Randazzo’s songs were as good as Burt Bacharach’s.

Better. He was such a genius and he looked at me as having a unique voice he could work with. We got back on the charts with I’m On The Outside (Looking In). Then we were in New York and he was in Europe. He was flying back and he was arriving at 6.30am. He wanted us at the office at 8am. 8am, man, come on! He had a little upright piano against the wall and he said, “Listen to this.” Boom, ba, boom, he was really dramatic on the piano. Then he started singing, “Well, I think I’m going out of my head…” That beat was different from any beat we had heard. We all went, “Hey, that song ain’t bad! Is that for us?” He said, “I want you to rehearse it and we’ll record it in three days’ time.”

The song was then recorded by Sinatra.

Yes, Don Costa was his conductor and arranger and he did it first on a TV special with Ella Fitzgerald. He loved that song. I never met him but he said to Don, “Tell that kid he sings good.” The song has been recorded by artists throughout the world. Amy Winehouse did I’m On The Outside (Looking In) and Kylie Minogue topped your charts with Tears On My Pillow. It’s good to come over and find that the fans know the words.

In 2009 you and The Imperials were inducted into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame…

We had been nominated before but never got there. I think that happened nine times! But this time there was a difference because Paul Simon and Billy Joel were on the committee, and they both loved us. Clarence Collins and I were told to be by our phones at a certain time, and Clarence said, “They are not going to tell us to do this if we’ve lost out again.” When I heard we were going to be inducted, I hit my fist in the air and said, “Yes!” Artists do like to be recognised. Now I’m in there with The Beatles; I’m in there with Michael Jackson; I’ve got my own little place in there. My great-grandchildren can come and see it long after I have gone from this earth.

Well, hopefully that won’t be for a long time. Are you still recording?

A couple of months ago, I was asked to contribute to an album that Paul McCartney is making to celebrate the 45 and he wanted me to do the Peter & Gordon song, A World Without Love. Sony are so happy with it that they have asked me to make a new album, Duets, with some major artists. So I’ve become like an antique chair that everyone wants to sit in… no, that doesn’t sound quite right!

An elder statesman perhaps?

An elder statesman, I like that. You English can put things so diplomatically. I’ll remember that. David Gest calls me a national treasure, but I like elder statesman better!

Are you enjoying being in the UK?

Yes, for years, I’ve had this thing inside of me, saying, “You’ve never been to England,” and then David Gest invited me over. He told me that the audiences would love to hear my voice. The shows were great. A lot is happening to me now. I’ve got my autobiography coming out, My Journey, My Destiny, and I would like to get it out in the UK. I’ve been blessed with a voice that is supernatural; I know it’s not natural. I’ve got it on loan from God. No one is supposed to sing like this at my age! People say I am singing better than ever, but whatever happens to me, I am at a peace with the world.