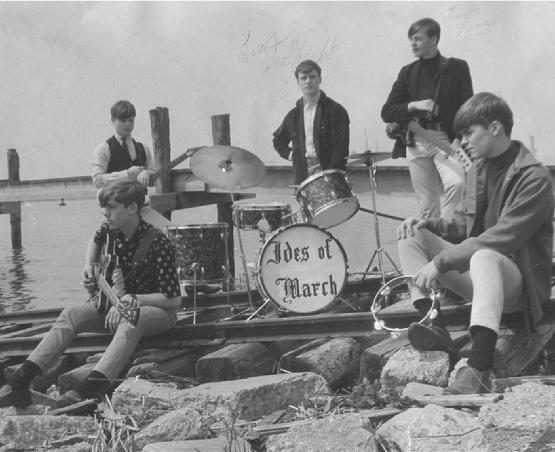

I did a crappy thing. In September 2014, I spent the day with Jim Peterik, the fabled Chicago songwriter and performer who launched not one but two incredibly influential pop bands, the Ides of March and Survivor. We ate lunch, and then I was his guest at an intimate friends-only concert he gave at The Cutting Room that evening. The idea was that I was supposed to interview him to give some pub for his then-new memoir, Through the Eye of the Tiger: The Rock ‘n’ Roll Life of Survivor’s Founding Member.

And then I didn’t write the article.

The problem is that I love this guy’s work, unironically and fully. Jim Peterik has been one of my favorite songwriters since I crawled out of my crib informing everyone that I’m a poor man’s son with a bad guitar and a simple song. “Hold On Loosely.” “Heavy Metal.” “Rockin’ Through the Night.” “Vehicle.” Just hit after perfect hit. I can picture watching Rocky III in Julie Kaufmann’s family room. I would place that opening montage with “Eye of the Tiger” up there with Tony Manero’s walk during “Stayin’ Alive,” “Don’t Dream It’s Over” during the fireworks in Adventureland, and “The Concept” during the road trip in Young Adult among the most perfectly matched song-movie combos ever. There are at least five distinct hooks in “I Can’t Hold Back,” every one of them amazing on its own, and within that kinda disposable pop confection, there’s really complex song structure at work. Just try diagramming that song with its weird half bridges and the verse starting right in the middle of a bridge.

So I love this guy, and because it’s kind of my thing to take seriously culture that smart people look down their noses at, I was eager to interview him and make the case that he deserves to be appreciated alongside Cheap Trick and Big Star.

The problem is the book kinda sucks. I will read just about any rock memoir, and as a failed rock musician, I can almost always find a thread in there—the elemental nastiness, the drug-addled mistakes, the sex-fueled rampages, the business disasters, it’s all relatable. But Peterik is just this really nice guy who did well for himself, married for 40-plus years to his high school sweetheart and just happens to write the filthiest hooks ever. Unfortunately, he’s way better at writing catchy choruses than autobiography. This thing was both way too short and way too boring. And then when I met him, I liked him so much I fell into that thing of not wanting to hurt the feelings of a guy who had grown on me—a fatal trap for a journalist. The last straw: When I went to the friends-only show, he played a golden rarity, the great Ides song “L.A. Goodbye” and dedicated it to “Ken, this really nice writer I spent the day with.”

I shitcanned the piece I was going to write.

But this summer, Peterik released a new record, The Songs, that reinterprets some of his biggest hits. Even without the layers of production sugar, the bones are just so solid. I went back to my original interview, and now, without needing to promote the book, I can present it with a clear conscience. In fact . . . I can’t hold back.

Observer: I’m from Chicago and have rock music in my own past. It’s a joke for me to say that to someone who’s achieved what you have, but some of the places you mentioned like Orphans where you were sort of discovered in your solo career are very familiar names to me. So tell me about coming to New York as a young Chicago rocker.

Jim Peterik: Well the first experience was 1970. I had never been to New York and the Ides played a NBC premier at a convention center, like NBC convention center. We had a No. 1 record. And it was like a society thing, and we’re in the lobby playing. It was very awkward and very weird. But flash-forward about a year and a half later, and we were booked at the Bitter End, and that was fun. We had just played Miami Beach at the Swingers Lounge and then flew to New York City and played the Bitter End for three nights and just killed. The first time I was in New York, I was freaked out by it. The energy was almost too much. I felt like there was so many people, and I was used to being a big fish in a small pond in Chicago. Suddenly, I was one of the masses in New York City. I didn’t know how to handle it. But the second time at the Bitter End, that stay I started getting comfortable with it. I played the Meadowlands many times with Survivor, when “Eye of the Tiger,” and that was a huge thrill. We played with REO Speedwagon. I remember that night Irv Azoff, the poison dwarf, he was courting us for management. I’ll never forget it because you know he came up to us after the set, and he said, “Hey, Jim, how are you doing? I really like your band.” Well we ended up signing with him. Frank [Frankie Sullivan, Survivor co-founder and guitarist] used to go out in the audiences wireless and on scaffolds and doing all the things I wish I was doing basically.

Well, you had developed your own sort of stage moves and persona, but you seem like such a cerebral part of the rock experience, the writer and stuff.

Well, yeah, there’s two sides to me. You know it’s the me that’s trying to write a good message in a good melody for a song, but then when you get out there, I mean was always a very . . . Well, they call them hams, but it’s more than a ham—I just love to perform. When I saw Springsteen perform, this was before he really broke. He was at the Auditorium Theater in Chicago. This is before wireless guitars, and he had a 200-foot cable. During “Spirit of the Night,” he got out into the audience and walked on the— He straddled the aisles and was rocking on the arm rests, and I was at the end. And there is Springsteen with his Telecaster, and I said, “Karen, I just saw God.” I was already a showman …

How old were you at about that time?

I saw Springsteen in ’74.

So you had already experienced quite a bit of rock success.

Oh, yeah, but it took it up another notch you know when I saw Springsteen. But I remember we opened for Sha-Na-Na at the Arie Crown Theater, and I had my Les Paul, and I used to do this thing where I put it under my chin, and during the jam on Eleanor Rigby, I used to do [sings] da-da-da-da-da-da do-do-do-do-do, and it was just really corny, but the crowd loved it. The reviewer the next day just lambasted me for it and said, “When he put that guitar and pretended to play a violin, I almost died laughing.” You know what? Critics never . . . I was never a critics’ darling.

Critics resentfully hate the kind of music that nakedly looks for hits, but I think there’s been a reckoning that what you were producing had merit. The same happened with REO Speedwagon, and it feels like there’s been a reassessment, that the stuff just really holds up in a way that nobody in 1981 would have predicted.

I agree. Sometimes success works in funny ways. We had all these top 10 records with a fair amount of No. 1 records, but we were on Solid Gold instead of Don Kirshner’s Rock Concert, you know, and Solid Gold doesn’t exactly hold the cachet of those other shows. Rolling Stone reviews used to scathe me, and you know Rolling Stone is my Bible, and I’m on the road with the Ides, and there used to be this town called Condemned, and there was this little guy hanging, a little cartoon, and then Vehicle by the Ides of March. I’d spend about two weeks in a deep depression. Then I learned, You know what? It doesn’t matter.

Speaking of deep depression there’s a good story in the book where you seem to open for all these cool bands. You’re opening for Boston, your first sort of solo gig trying to be a solo artist. And Bradley Delp is scared to go out, and later on his life ends in the most unbelievably gruesome suicide. These bands that do this kind of confection style pop, you don’t think that there’s these horrible depressed feelings swirling around. Talk about how you have had this very stable family life, this very stable emotional life amid all these really upsetting circumstances.

Well, you know what I say in the book in a different way is that when I started . . . You know I hesitated to write this book for 10 years mainly because I didn’t think I had enough drama in my life you know. I didn’t have the train wrecks that individual members of Duran Duran and Motley Crue had. First of all, I’m a voracious reader of rock bios and autobiographies. Like Rick Springfield’s Late, Late at Night. I thought it was excellent. He talks about depression and the visitations that he used to get. I love that book. I loved Howard Kaylan’s book. You don’t have to be the biggest star in the world to write a great book, and of course, I loved the Turtles. That’s where I met my wife, waiting in line to see the Turtles. But I read these books, and there’s so many train wrecks, and there’s a part of human nature that loves to watch a train wreck and can’t look away. So I’m going, “Is there enough tension in my life?” But as I started writing, I started crying when I’m talking about almost losing my marriage for being on the road for 10 years and the power struggles with Frankie and Frankie’s passive aggressive tactics. I said, You know what, there’s a lot more conflict in my life than I thought, and you know why? I always covered it up with songs. I always went to my room and poured out any emotions I had into the songs that became like a shield. But you take that shield off, and I had as hard a life as most anybody. It’s just that’s how I dealt with it.

I’m a big enough fan that I’m very familiar not just with Ides of March and Survivor but also with a ton of your collaborations from 38 Special to Brian Wilson. What I hadn’t really appreciated until reading the book is your time as both a professional songwriter—Reba McIntyre and Johnny Rivers—and also the jingle stuff. The Sunkist one? I mean, you kind of ruined my life with that song.

[Sings] I’m drinking up good vibrations, Sunkist on the taste sensation…whaaa whoop whoop. I’m embarrassed.

And the Schlitz one?

[Sings] Look out for the bull. Look out for the Schlitz Malt Liquor Bull. Nobody makes malt liquor like Schlitz.

I remember that melody! There was one that any Hawks fan would remember from listening to hockey on the radio: [sings] From the land of sky blue

[Sings] From the land of sky blue waters. I did one of those.

Did you? I thought I heard you on there.

Absolutely. That was about three years of royalties—Hamm’s Beer.

So talk to me a little bit about why you can’t get your head around performing Survivor stuff.

When I left Survivor in ’96, I forfeited the name, and the reason I was so easy on it—first of all, I hate courtrooms, and I didn’t want to go through a long battle, which it would have been with Frankie. So, I said, “Here’s the name,” and here’s why: I felt that, and it may sound egotistical, but without me as the musical leader that name would not be worth fighting for. I was the musical quarterback of that band. I was the bandleader. I ran them through everything—the arrangements, the discipline at rehearsals. When that’s not there, you don’t have a quarterback, and it proved to be true. So I went back with the Ides. Actually, I had reformed the Ides before that in ’91 or ’90, and we were doing gigs. That’s when Survivor was kind of hit and miss, and Jimmy had his own version, and it was kind of a nightmare. And I said, well, Berwyn, Illinois offered us quite a bit of money to get back for one show. We rehearsed for three months, and in the summer of ’90, Ides did this concert for 25,000 people in Berwyn. We said, Hey, man, we worked for three months; we’re not going to do just one show. That year we did maybe five shows, and every year it built. I was back with my family. And you’re right when you mentioned Survivor was more of a business entity than anything, and they resented—especially Frankie—resented any kind of writing I did with anybody else even if I couldn’t have written those songs with Survivor and it wouldn’t have been the right brand. Whereas, Ides of March, it was, “Yeah, you go, Jim. What’s good for you is good for all,” and it was just a total supportive environment. I had known the Ides guys since Cub Scouts, and I was back. And I figured, I’ve got these songs—they are my children. I can do what I want with my children. It doesn’t have to be Survivor playing “Eye of the Tiger”; it can be the Ides with the brass going [sings] bap bap bap bap.

Does it annoy you, though, that those songs are still being played by an entity called Survivor?

You know, if they’re doing good shows, I don’t mind. If they’re dogging it—and I’ve heard mixed reviews.

Have you seen them?

I have not. I purposely have not.

I know a little bit about songwriting and how the money part of it works. You said that you got a lot of money to reform and whatever that money was, it can’t be the equivalent of what you must see in your mailbox all the time from your work. I hear your songs on the radio all the time, today.

Right. Well, that’s why I had to weigh my options. I got a call from Jimi maybe eight months ago feeling out whether I wanted to rejoin on the keyboards. Him singing, Frankie on the guitar.

[Survivor’s original singer was Dave Bickler, who went on to be the voice of Budweiser’s “Real Men of Genius” campaign. He was replaced by Jimi Jamison, who died in September 2014, just a few days before this interview was conducted.]

Until about six months ago, there were two lead singers. Dave and Jimi were sharing lead vocals. David Lee Roth and Van Halen, yeah, [Peterik means Sammy Hagar]. And Jimi starts—obviously, Frankie put him up to this because Frankie wouldn’t call me direct. You know we don’t have that kind of relationship. So Jimi is giving me the kind of heart and soul: “It’s really great man. We’re singing great, we’re playing great—blah blah blah.” He kept talking, and I realized that it was still Frankie’s show, and it was not going well, and he ended up saying, “Jim, you don’t want to be out here.” And that was the last . . . he had to be honest because he’s my friend.

Your descriptions of your relationship with Frankie are really well wrought. You maintained respect for him as a musical collaborator this whole time, and yet it’s so clear how hard it is to be a room together.

Well, the only time it was comfortable, and I say he put a straw hat and cane on and came to the writing session because he knew that’s where the bread was buttered, publishing, and I enjoyed Frankie so much when we were writing together. He was a strong songwriter.

He’s a riff guy.

He was a good riff guy, but I’m a good riff guy too. A lot of the riffs that people assume are Frankie’s are mine.

I probably am guilty of that myself. I have assumed the melodies, the ideas, the lyrics were yours, and then he was the riff guy.

Well, that did exist. I mean, “Caught in the Game” was definitely his riff, which is brilliant you know, but there’s other times where I created a riff, and of course “Take You on a Saturday” was his, but I could give you other examples that were mine. But he had great rock and roll test, and he was a great editor. And you know, even if he wasn’t in the room, if I knew I was going to be presenting an idea to Frankie, I would edit myself, make sure there wasn’t something was just too intelligent that people wouldn’t get or there was a chord wasn’t too left of center. He was very mainstream. Frankie knew the brand called Survivor, and that’s the biggest thing he added to the band. He didn’t like wimpiness, and that was a good thing.

So, you had real collaborations with 38 Special. You just cited it to our waitress. And not just “Hold On Loosely” but “So Caught Up In You” was also yours?

“Wild Eyed Southern Boys,” “Fantasy Girl,” “Chain Lightnin’,” “Keep On Running Away,” “Rocking Into the Night” …

Oh, I didn’t know that. That was like their first hit, right?

[Sings] Da da do do do. The timing is really weird on that. Someone says are you sure that timing is going to be commercial? Yeah.

Two drummers? What the hell is that about?

And neither of them were really good. One guy could hardly play. It was so bad. We were rehearsing with them in Jacksonville. I’m going, “Could you just not play?” That was the wrong thing to say. But no, that song, and it’s in the book, was supposed to be on the first Survivor record that Ron Nevison produced. And this was a big-stage song.

Who are all the co-writers listed on “Rockin’ Into the Night”?

There was Frankie Sullivan and Gary Smith, the drummer, which I just gave them. Gary Smith was Survivor’s drummer before Marc Droubay. He played only on the first album. Marc Droubay and Dennis Johnson were members of the group Chase prior to this.

You described that, but why did Smith participate in the songwriting? Is that typical?

No. It was probably the goodness of my heart. I gave Frankie credit because he did create the riff. [Sings] ba ba ba da don, which became a huge part of the song. He wrote nothing with the chords or lyrically.

It was generous of you to give these guys—

I’ve been very generous with that. Gary created the rhythm for [sings] Waiting Participating. His drum part inspired me to write that part.

And that gets a songwriter credit? This guy is getting checks to this day for making up the timing of a drum part?

They both are. But then I became like the villain because Kolodner [John Kolodner, the head of A&R at Atlantic Records] was like my guy because you know he thought I was the leader of the band, and I really was. So I got blamed and when that became a top 10 record for 38 Special— We would be in the car, and that song would come on, and Frank would just slam the radio.

I love these “story of the song” things. Tell me about “Vehicle.”

I just did a radio interview, and the manager of the station kept going on and on. He said, “What a thrill! The guy that sang ‘Vehicle.’ ”

I’m not surprised by that. That song is so special, so unusual for a radio hit. It’s kind of creepy too. I was playing it. I have young daughters, and I was telling them I’m going to interview a rock star hero, and my daughter is like, “Friendly stranger in a black sedan?”

And here I’m 19 singing about it. I think I might have told in the book what happened. It’s funny, you know Hardees just did a commercial on it— Hardees and Carl’s Jr and they played it up. They played up that friendly stranger thing. They have this actor sitting on a black sedan eating a chicken sandwich. I was sitting with my stoner lab partner in biology, and he’s laughing, “Jim, look at this!” This anti-drug pamphlet that was circulating through the school. And there was this little caricature cartoon of the friendly stranger to be aware of, and he was in a black sedan you know. I’m the friendly stranger in the black sedan—would you hop inside my car? I was looking for that first line. Prior to that it was [sings] I’ve got a set of pretty wheels pretty baby won’t you hop inside my car. It didn’t have the rhythm.

Do you remember a Chicago band called The Kind?

Of course. Yeah, Frank . . .

Everyone was Frank in that band, a typical Italian Chicago band. They had a hit called “Loved By You.” They and Off Broadway, both highly influenced by you.

Well, I mean Cliff and I still— He was on the world stage. You know, I do these world stages, kind of my Ringo Starr review, about twice a year, and he was on at least two years of shows. We were doing a lot of— I mean “Bully Bully” and all those great songs, “Keeping Time” and “Don’t Get Out of Line.”

“Stay in Time.” That’s a great song.

You’re a guy who knows his rock.

That’s the greatest compliment I’ve ever gotten.

Put that recorder on pause. I want to tell you something about Cliff . . .