In April this year Merriam-Webster expanded its dictionary. To “stan” is “to exhibit fandom to an extreme or excessive degree”. Whether self-deprecatingly ironic or alarmingly sincere, stans are inescapable: from Benedict Cumberbatch’s Cumberbabes and Beyoncé’s Beyhive to burrito buffs and avocado aficionados. The word can also be used as a verb: as in “We stan a legend.”

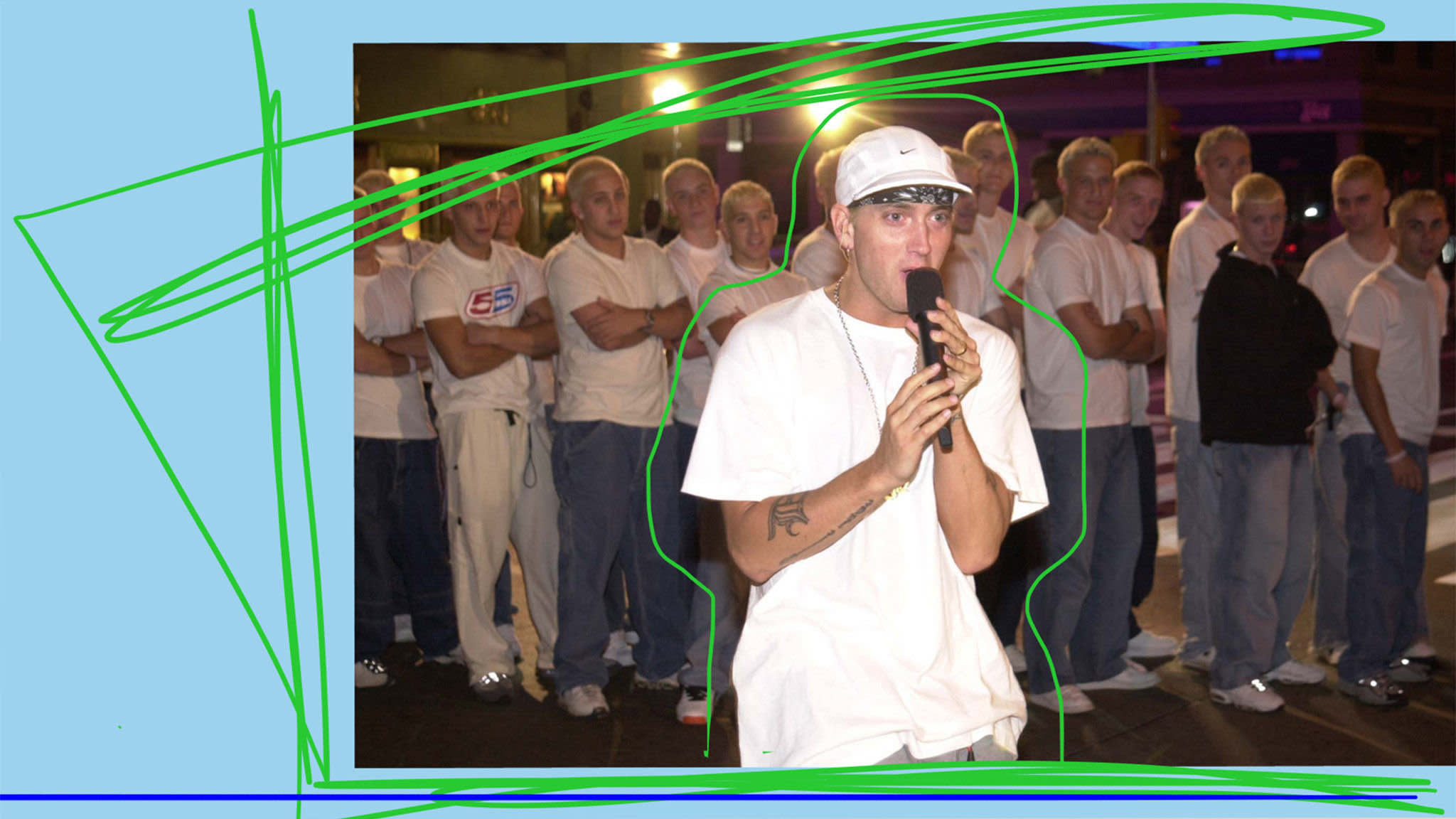

A portmanteau of “stalker” and “fan”, the word is attributed to the notorious Marshall Bruce Mathers III, aka Eminem, who studied the dictionary in his youth to amass ammunition for his lyrical arsenal.

Few songs probe the artist-fan dynamic as disturbingly as his chart-topping 2000 single “Stan”. An epistolary short story, “Stan” stretches the narrative possibilities of rap, examining fan entitlement, their delusions of shared experience and the unwelcome visibility of sudden superstardom. Enraged by his idol’s apparent indifference to his existence, Stan drives off a bridge, killing himself and his pregnant girlfriend trapped in the trunk.

Though its instrumental is austere, the song has a filmic quality. A steady downpour and rumbles of thunder soundtrack Dido’s gauzy, doleful vocals — a sample from her sleeper hit “Thank You”. Stan’s pencil scribbles away, forming indents and creases on the page as his emphasis grows more pointed. Later we hear muffled screams as his car plunges into water.

Though its lyrics are more conversational than the intoxicating assonance of sledgehammer rhymes that typify his raps, “Stan” is arguably Eminem’s most thoughtful and thought-provoking songwriting. Stan interprets as gospel the sermons of Slim Shady — to some Mathers’ cartoonish alter ego, to others a cover for his vilest impulses. He even enacts his idol’s lyrics: “Hey Slim, I just drank a fifth of vodka, dare me to drive?” he slurs, quoting the 1999 single “My Name Is”.

Eminem acknowledges his cultural influence but denies culpability for Stan’s actions. Yet on The Marshall Mathers LP, one of the bestselling albums of the decade, “Stan” sits uneasily between the hyperviolent “Kill You” and “Who Knew”, which mock gay men and joke about choking “whores” and raping “sluts”. Given the rapper’s measured advice that Stan treat his girlfriend better, misogynist murder fantasy “Kim” is particularly jarring; Eminem’s ventriloquised victim is not a persona like Slim Shady but his then wife. Such songs are deliberate acts of provocation. Frequently accused of corrupting white America’s suburban youth, Mathers goads his censors by doubling down on his freedom to offend. If Slim Shady anticipated stan culture, he was also a proto-troll.

While LGBT+ and women’s rights groups protested outside, Elton John controversially performed “Stan” with Eminem at the 2001 Grammys. The duet marked the start of a lasting friendship. The singer once referred to “the meanest MC on earth” as “you gorgeous thing” while Mathers’ wedding gift to Elton and David Furnish was “two diamond-encrusted cock-rings on velvet cushions”. John insists they remain unused.

“Stan” is a common reference point for US and UK rappers. Nas cemented the song’s place in the hip-hop canon by deriding Jay-Z as a “stan” on “Ether”. Lil Wayne inverted its concept in a series of appreciative, confessional letters to his fictional “number one fan” in “Dear Anne”, though he rightly deemed it too weak to be album-worthy. In 2017 Mancunian rapper Bugzy Malone’s “Dan” smartly updated Stan’s story for today (“Yo Bugz, I hit you up on Snapchat”). Meanwhile Arizona singer-songwriter Alec Benjamin commits the heinous acoustic-rap cover crime of sentimentalising: his vocals carry all the threat of a woolly cardigan.

In 2013 Eminem revisited “Stan”. The Marshall Mathers LP 2 opens with its sequel “Bad Guy” where Stan’s younger brother Matthew exacts revenge. Mathew’s stilted, prickly flow may lack his brother’s unhinged lucidity, but his motives transcend fraternal loyalty. Matthew claims he represents “anyone on the receiving end of those jokes”, including women and homosexuals.

Despite “Bad Guy”’s apparent contrition, some stans’ loyalty remains unimpeachable. When Eminem called rapper Tyler, the Creator a “faggot” last year, fans rushed to his defence. Perhaps Em’s letter didn’t reach them in time. Perhaps they weren’t paying attention. Even when Eminem later apologised, the Real Slim Shadys still stanned up for their idol.

What are your memories of ‘Stan’? Let us know in the comments section below.

‘The Life of a Song Volume 2: The fascinating stories behind 50 more of the world’s best-loved songs’, edited by David Cheal and Jan Dalley, is published by Brewer’s.

Music credits: Universal Music Group International; Sony BMG Music UK; Polydor Associated Labels; Columbia

Picture credit: Jeff Kravitz/FilmMagic, Inc