When Aaron Copland was awarded an Oscar for his score for William Wyler’s 1949 film The Heiress, he never bothered to pick up his statuette. The reason: Wyler had had large sections of Copland’s music re-scored, particularly in the opening credits, making greater use of a melody that Copland had employed only passingly — an old French song called “Plaisir d’Amour” (sung in the film by Montgomery Clift to Olivia de Havilland). Copland hated the fact that this sweet tune had supplanted chunks of his own score. The episode effectively ended the composer’s association with Hollywood.

The song went on to divide opinion, between those who thought it a haunting melody and adapted it for a new audience, and those who, like one composer, saw it as the aural equivalent of Heinz beans. It was written in 1784 by Bavarian-born composer Jean-Paul-Egide Martini, adapting a poem which appeared in a novel, Célestine, by Jean-Pierre Claris de Florian. Over the years, various composers arranged it, including Berlioz (1859).

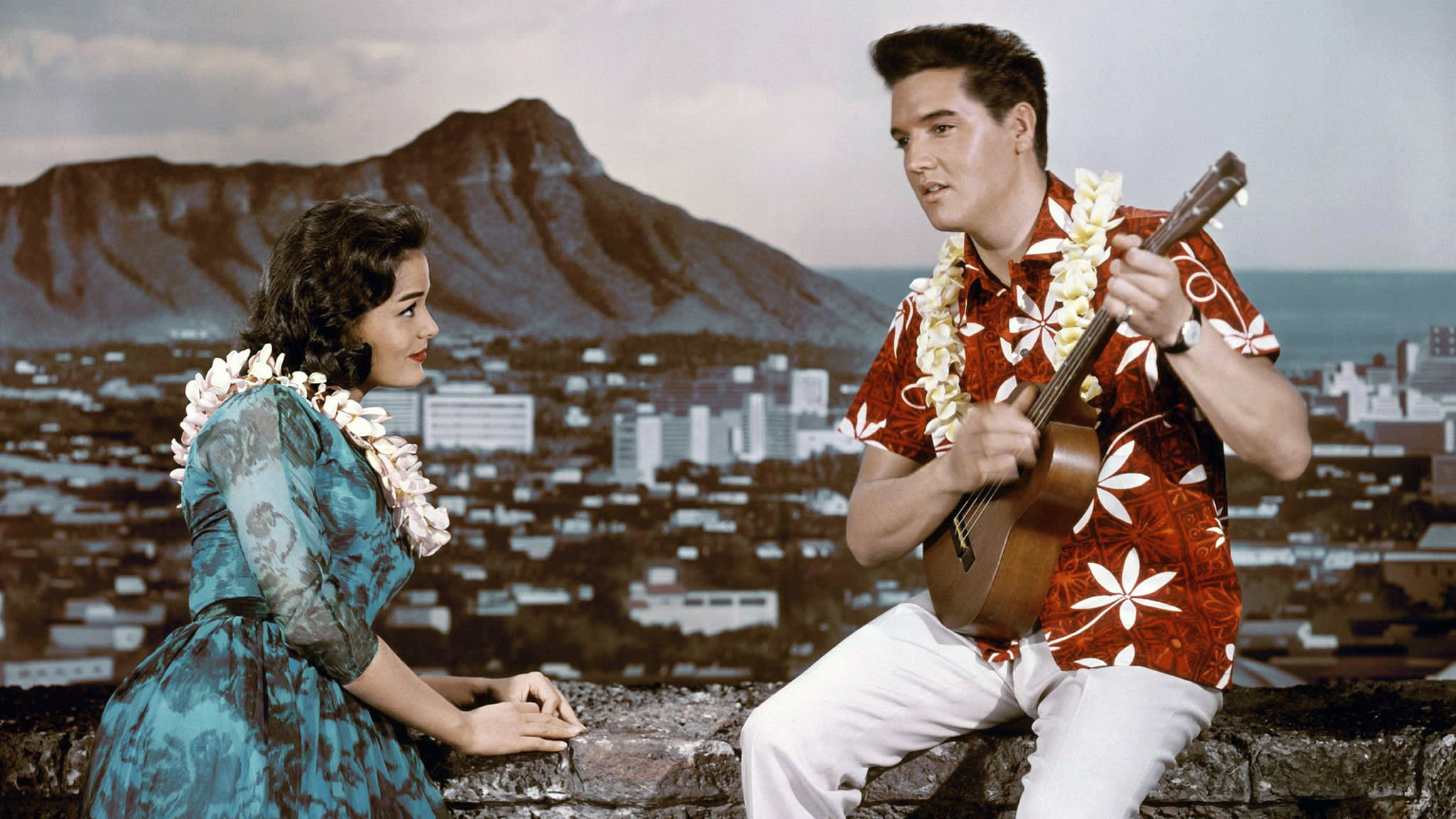

But the tune became best known as the melodic basis for one of Elvis Presley’s biggest hits: “Can’t Help Falling in Love”. And here, again, there is Hollywood connection: the song was written by George David Weiss (who also wrote Louis Armstrong’s “What a Wonderful World”), along with Luigi Creatore and Hugo Peretti, for Presley to sing in his 1961 film Blue Hawaii. Weiss later said that the film’s producers didn’t think it was sufficiently “rock and roll” for Elvis, but Presley himself accidentally overheard a demo of the song and insisted that it be used in the film. (The singer, however, struggled with it in the studio, needing 29 takes to get his breathing and delivery right.)

In Blue Hawaii, Presley gives a music box as a gift to his girlfriend’s grandmother, saying that it plays “a European love song”; when he opens it, it tinkles the opening arpeggio, after which Presley takes over the tune. Presley also says that love songs are “the same in any language”, but Weiss’s lyrics suggest otherwise. They stand in marked contrast to the words of “Plaisir d’amour”; the differences exemplify the gulf between two eras and two cultures. “Plaisir d’amour” complains, in a very French-romantic fashion, that “The joys of love are but a moment long/The pain of love endures the whole life long”. “Can’t Help Falling in Love”, on the other hand, has a more upbeat vibe, reflecting postwar American optimism and seizing on the inevitability of love, “Like a river flows surely to the sea”. It became a huge hit for the singer, and was the song with which he ended his concerts during the 1970s.

Hundreds of versions followed. In 1970 Andy Williams released what remains perhaps the finest reading of the song: dispensing with the lilting time signature of Presley’s version, the crooner is backed by a glistening, joyful big band that flows like… well, like a river. In 1976 The Stylistics gave it a disco beat and a sheen of Philadelphia brass and strings. On their 1992-93 Zoo TV world tour, U2 would end their shows with Bono singing it (moving into an impressive falsetto), before leaving the stage as Elvis’s version played over the PA. Also in 1993, UB40 had a worldwide hit with their lightweight, reggaefied recording, while Erasure electro-fied it in 2003 on their covers album, Other People’s Songs. American singer Beck recorded a sombre version — brushed drums, brooding vocals — for a tie-in album with the Amazon TV adaptation of Philip K Dick’s “if the Nazis won the war” novel, The Man in the High Castle.

“Plaisir d’Amour”, meanwhile, lived on. In the 20th century it was recorded by classical singers such as Plácido Domingo and by popular singers such as Joan Baez (in French and English.) It was also adapted as a hymn, “My God Loves Me”, still sung worldwide in Christian worship.

But resistance to the tune has endured. In 1990, Copland’s music for The Heiress was reworked by Arnold Freed into The Heiress Suite, an eight-minute work in which “Plaisir d’amour” appears only fleetingly, an afterthought. And Copland’s experiences resonated with André Previn, who wrote in No Minor Chords, his 1991 book about his own Hollywood days: “It [Copland’s score] begins with music under the credit; music that is slick, pretty, and utterly vapid.” (He means “Plaisir d’amour”.) “Then, suddenly, approximately two minutes along, there is a gearshift, and Copland’s music takes over, spare and angular and gorgeous. It’s like suddenly finding a diamond in a can of Heinz beans.”

Haunting or sickly? What’s your view of this tune and the many versions of it? Let us know in the comments section below.

‘The Life of a Song Volume 2: The fascinating stories behind 50 more of the world’s best-loved songs’, edited by David Cheal and Jan Dalley, is published by Brewer’s.

Music credits: RCA/Legacy; Sony Music Entertainment; Amherst Records; Rhino; Mute, a BMG Company; 30th Century Records; Sony Classical; AVID Entertainment; RCA/Red Seal

Picture credit: Sunset Boulevard/Corbis via Getty Images