Do you recall what was revealed?

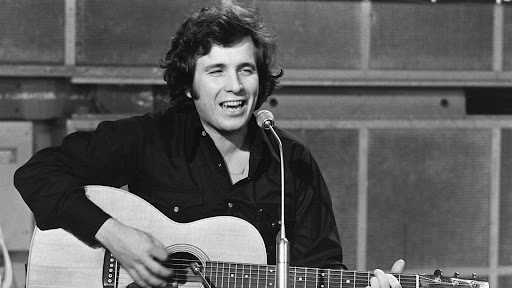

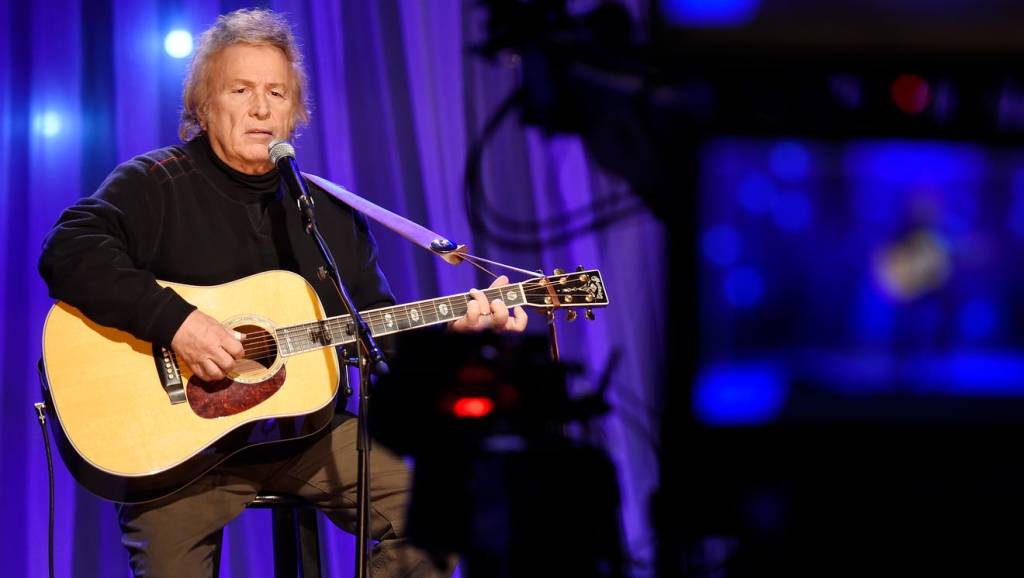

I’ve recently written a couple blogs that delve into the meaning behind some classic rock song lyrics. When I happened to mention to a few folks that I would be writing a blog post solely about Don McLean’s iconic opus “American Pie” — seeing as how it was released 50 years ago this week — one friend said, “Oh God, please don’t. Tell me when that’ll be published so I can skip your blog that week.” Others said they were looking forward to it, recalling the great memories the song evokes for them.

Either way, here we go.

“American Pie” is quite possibly the most (over)analyzed song in rock history, which was pretty much what McLean, now 76, had been hoping for. “It turned out beyond my wildest dreams,” he said in a 2020 article in American Songwriter. “I wanted to write a big song about America, so I came up with this idea that politics and music influence one another and flow parallel together, forward, but I had no clue how to begin to express that. Then one day, I was singing into the tape recorder, and the first verse all came tumbling out, like a genie from the bottle. ‘A long, long time ago’ all the way through to ‘the day the music died.’ I thought, ‘Whoa, what is that?!'”

One of the motivating factors in McLean’s songwriting through the years has been a family secret that McLean never discussed openly until recently. He had a sister, fifteen years his senior, who was an alcoholic and drug addict “who almost ruined my childhood. It was a disaster to see it. It was just awful. That’s one big reason why I’m a blue guy, I guess. All my songs are about loss – and a certain kind of psychic pain. I’ve never really been happy.”

McLean had a decent career, with several other popular singles like “Vincent” (a #12 hit) and “Dreidel” (#21) and a cover of Roy Orbison’s “Crying” (#5), but without question it was “American Pie” that defined him… and sustained him… and exasperated him as well. It was a mighty bold undertaking to attempt a song that chronicled the rise and fall of rock & roll in an infectious and expansive radio-friendly pop song, and everyone has been relentlessly asking him what the words really mean. His pat answer was always, “It means I don’t have to ever work again if I don’t want to.” (Indeed, he pulls in about $400,000 in annual royalties, and the handwritten lyrics fetched a cool $2 million at auction in 2015.)

But he’s been talking about it more openly these days. I have researched numerous articles and essays, published long ago and more recently, to assess various interpretations that either confirmed my thinking or put forth something entirely different. Today, I offer my view on the words that many of us can and still do sing along to when the song is played.

*********************

A long, long time ago,

I can still remember how that music

Used to make me smile,

And I knew if I had my chance

That I could make those people dance

And maybe they’d be happy for a while

But February made me shiver

With every paper I’d deliver,

Bad news on the doorstep,

I couldn’t take one more step,

I can’t remember if I cried

When I read about his widowed bride,

Something touched me deep inside

The day the music died

McLean was a 14-year-old paper boy on February 4, 1959, when he was sucker-punched by the headline about the plane crash that took the life of Buddy Holly and two other vintage rockers. He had loved Elvis and Chuck Berry and Little Richard, but they had joined the Army, gone to jail and converted to gospel music, so when Holly went down too, McLean felt as if a chapter of his life, and what he regarded as the innocent life of ’50s America, had come to an end. Compounding this in real terms is the fact that McLean’s father died the next year, leaving him on his own to figure things out. He felt it acutely at age 26 as he began writing the song in 1971 and realizing how much had changed in only a dozen years. Something indeed touched him deep inside, and he was moved to write it all down in five more lengthy verses and a repeated chorus.

***********************

So, bye-bye, Miss American Pie,

Drove my Chevy to the levee, but the levee was dry,

And them good ol’ boys were drinkin’ whiskey and rye,

Singin’, “This’ll be the day that I die,

This’ll be the day that I die”

Here he is singing a fond farewell to childhood, to apple pie and Miss America. Some of you may recall the old TV commercial with the tagline, “See the U.S.A. in your Chevrolet…” That’s how the Chevy reference ties in, but he’s finding the well of innocence has run dry for him. In another nod to Buddy Holly, McLean altered his song “That’ll Be the Day,” turning a romantic negotiation into something far more solemn. McLean’s mourning for simpler times is initially set to a slow, ballad tempo, and again in the song’s coda, but the majority of the record gallops along as an infectious, uptempo romp that kept most of our melancholy musings at bay while we sang along. Very clever of him to put all these thought-provoking lyrics to a pleasant, sing-along melody, or the entire enterprise might have never been noticed in the first place.

Alexis Petridis, music critic for The Guardian, summed it up this way: “Dylan talked to us in dense, cryptic, apocalyptic terms. But McLean says similar ominous things in a pop language that mainstream listeners could understand. The chorus is so good that it lets you wallow in the confusion and wistfulness of that moment, and be comforted at the same time. It’s bubblegum Dylan, really.”

************************

Did you write the book of love

And do you have faith in God above

If the Bible tells you so?

Now, do you believe in rock ‘n’ roll?

Can music save your mortal soul?

And can you teach me how to dance real slow?

Well, I know that you’re in love with him

‘Cause I saw you dancin’ in the gym,

You both kicked off your shoes,

Man, I dig those rhythm and blues,

I was a lonely teenage bronckin’ buck

With a pink carnation and a pickup truck,

But I knew I was out of luck

The day the music died

It’s crystal clear that McLean is weaving spiritual thoughts into the lyrics at several points, most notably here, where he uses the 1950s hit songs “The Book of Love” and “The Bible Tells Me So” to compare faith in God with faith in rock ‘n’ roll music (as the Lovin’ Spoonful had asked in “Do You Believe in Magic?” in 1965). McLean takes us back to sock hops, cool cars, great dance tunes and how “I knew I was out of luck” because his innocent childhood had ended. He felt it was useless to keep yearning for those old days now that so much had transpired by the time he wrote the song in 1971, as we shall see.

***********************

Now, for ten years we’ve been on our own,

And moss grows fat on a rollin’ stone

But that’s not how it used to be,

When the jester sang for the king and queen

In a coat he borrowed from James Dean

And a voice that came from you and me

Oh, and while the king was looking down,

The jester stole his thorny crown,

The courtroom was adjourned

No verdict was returned,

And while Lenin read a book on Marx,

A quartet practiced in the park,

And we sang dirges in the dark

The day the music died

Here the lyrics start to become a more interesting guessing game. Who is the Jester? The King and Queen? What courtroom? Who is the quartet practicing in the park?

Bob Dylan has dismissed the notion that he might be the Jester in McLean’s story (“A jester?” he scoffed. “Sure, the Jester writes songs like ‘Masters of War’ and ‘A Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall’ – some jester. I have to think he’s talking about somebody else.”). But it makes sense from the standpoint of Dylan assuming the musical mantle in 1963 that had been cast aside by The King, who is, of course, Elvis. The coat Dylan borrowed from James Dean — symbolically, anyway — can be seen on the cover of his landmark “The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan” album.

Some observers saw the lyrics here as more political. The King and Queen, they say, were John and Jackie Kennedy, and the Jester who stole the thorny crown was Lee Harvey Oswald. An intriguing idea…and this would actually tie in nicely to McLean’s premise about our national loss of innocence, but I’m not buying it.

The courtroom was the court of public opinion, where people’s tastes in music were splintering into different factions (folk versus rock, etc.) and, hence, no verdict was returned. Again, in the matter of Kennedy’s assassination, many in the court of public opinion never accepted the Warren Commission’s conclusions, which can translate to a “no verdict.”

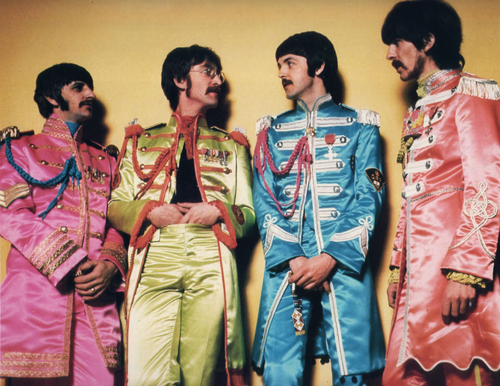

The quartet who were honing their skills in 1963, I think we can all agree, were The Beatles, whose seismic impact on rock music was about to be felt. Meantime, pop radio would be filled with inconsequential pablum — “dirges in the dark” — until their arrival.

************************

Helter skelter in a summer swelter,

The birds flew off with a fallout shelter,

Eight miles high and falling fast,

It landed foul on the grass,

The players tried for a forward pass

With the jester on the sidelines in a cast

Now, the halftime air was sweet perfume

While sergeants played a marching tune,

We all got up to dance,

Oh, but we never got the chance

‘Cause the players tried to take the field,

The marching band refused to yield,

Do you recall what was revealed

The day the music died?

The merger of folk and rock symbolized by The Byrds and “Eight Miles High” in 1966-67 was the high point of ’60s optimism, which at first, rivaled the carefree sunniness of the ’50s. The “players” who “tried for a forward pass” were, I submit, The Rolling Stones, who were enjoying a string of edgy yet broadly accessible mid-’60s hits (“Satisfaction,” “Get Off My Cloud,” “Paint It Black”) while Dylan sat “on the sidelines in a cast,” convalescing from a motorcycle accident. With their milestone “Sgt. Pepper” LP in 1967, The Beatles had morphed from the quartet into the Marching Band, hoping to maintain the air of “sweet perfume,” but the false promises of The Summer of Love were dissolving, and “we never got the chance” to dance because psychedelia, acid rock and new tensions were on the rise.

The politically based interpretation says the “players” are the civil rights protesters, and the marching band is the authoritarian establishment who “refused to yield.” And what was it that was revealed? You can make the case that the seemingly intractable division between the political left and right that haunts us even more today than 50 years ago was first on display in the Chicago streets outside the 1968 Democratic Convention. It was the dark underside of the American Dream.

***********************

Oh, and there we were all in one place,

A generation lost in space,

With no time left to start again,

So, come on, Jack be nimble, Jack be quick,

Jack Flash sat on a candlestick,

‘Cause fire is the Devil’s only friend

Oh, and as I watched him on the stage,

My hands were clenched in fists of rage

No angel born in Hell

Could break that Satan spell,

And as the flames climbed high into the night

To light the sacrificial rite,

I saw Satan laughing with delight

The day the music died

This verse opens with a description of the crowd at a music festival, presumably Woodstock with all its good vibes, but we soon see it’s the darker, violent Altamont festival that McLean is talking about. “Fire is the Devil’s only friend” ties together “Sympathy for the Devil” and The Rolling Stones’ performance there, during which Hell’s Angels “security” beat a concertgoer to death in full of view of the red-caped Mick Jagger and the band on stage. To McLean, this was the nadir of the story’s arc, the moment when any hope of innocence returning had been dashed. The story, and the words he uses to tell it, get a bit melodramatic at this point, but he’s trying to drive the point home that nothing “could break that Satan spell.”

Listeners who were paying attention to the words at this point could be forgiven for concluding, “This is one depressing song.”

**********************

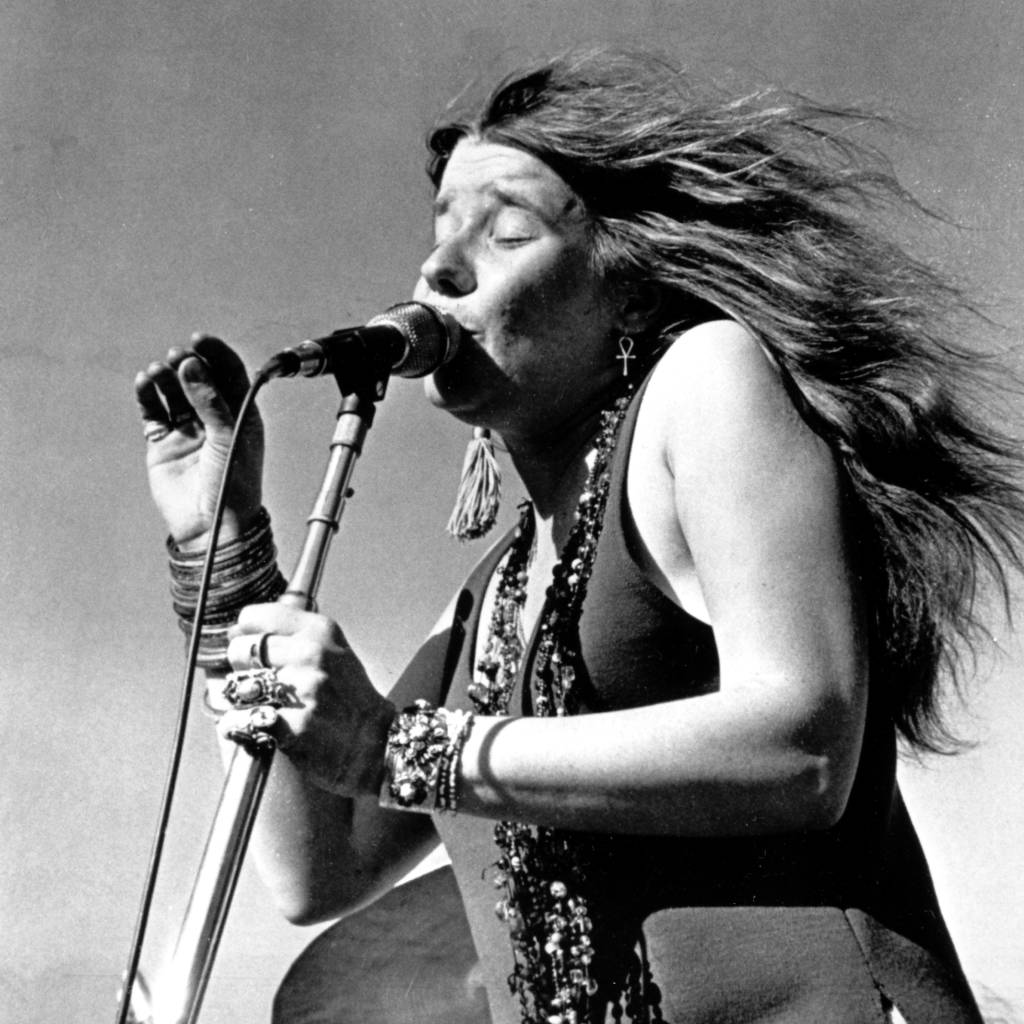

I met a girl who sang the blues

And I asked her for some happy news,

But she just smiled and turned away,

I went down to the sacred store

Where I’d heard the music years before,

But the man there said the music wouldn’t play

And in the streets, the children screamed,

The lovers cried, and the poets dreamed,

But not a word was spoken,

The church bells all were broken,

And the three men I admire most,

The Father, Son and the Holy Ghost,

They caught the last train for the coast

The day the music died

As the tempo returns to a slower, more reflective pace, McLean touches on the sad tale of Janis Joplin, whose career briefly shone brightly but ended in tragedy and drug overdose (“she just smiled and turned away”) in 1970. The “sacred store” where “the music wouldn’t play” was, I believe, the neighborhood record store, where there had once been listening rooms for buyers to check out records. More to the point, the music of McLean’s youth was now passé, shoved aside by the cynicism of the newer generation. The faith in music had not been rewarded — instead, “the church bells all were broken.” Everyone had abandoned the chance of innocence, even “the three men I admire the most,” the Holy Trinity, who chose to metaphorically skip town.

***********************

“American Pie” is, in essence, a cautionary tale about how, as Joni Mitchell once sang, “you don’t know what you’ve got ’til it’s gone.” Any interpretations of the lyrics, including mine, have to be taken with reservations, just as with any cryptic song lyric of that period, or any period. “Basically, in ‘American Pie,’ things are heading in the wrong direction,” concludes McLean. “Life is becoming less idyllic. I don’t know whether you consider that wrong or right, but it is a morality song, in a sense.”

Despite its catchy melody, there’s little to really cheer about in “American Pie.” McLean did come up with one more upbeat verse where the music gets “reborn” at the end, but he ditched it. “Things weren’t going that way,” he said in a 2020 interview. “I didn’t see America improving intellectually or politically. It was going steadily downhill, and so was the music.”

Here in 2021, you can make a convincing case that the innocent, simple days of 1950s America McLean longed for weren’t so innocent nor simple, especially not if you were Black, or Hispanic, or a woman who wanted to be something other than a housewife. And the civil unrest of the ’60s that McLean disparages was, in my view, a necessary battle that brought about some long-needed change in terms of voting rights and job/housing discrimination, to name just two areas.

But we’re talking about one man’s lyrical poetry put to music in 1971, describing the previous ten years. It’s a pop song — a major achievement in pop culture, to be sure — but still just a song. Let’s not assign too much importance to it.

Rob Patterson, a writer at the Best Classic Bands website, put it nicely in perspective: “It’s less important what McLean may say it means, and more important what it means to the listener – not who was what, but how it feels and its emotional impact. One of the true beauties of a great song is how it can become a part of your own experience, your feelings and your life.”

For me personally, “American Pie” is a song I like to play on guitar with a choir of family and friends singing along at the top of their lungs. People have told me they’re amazed I’m able to remember all the words, but that’s because they’re ingrained in my memory since I first learned them.

And to those who are sick to death of “American Pie” or never liked it in the first place, I say, you better look out. McLean announced recently there’ll be a documentary, “The Day The Music Died: The Story Behind Don McLean’s American Pie,” set for release at the end of 2021, and some sort of stage play in 2022 about McLean’s career and the song’s impact, and even a children’s book based on the song.

Apparently, the music, McLean’s music, never died after all.

***********************

The Spotify playlist below is short and to the point. First, of course, is “American Pie,” followed by eight tracks that are mentioned specifically or alluded to in the lyrics, and then concluding with “Vincent,” McLean’s sad ode to Vincent Van Gogh.