The mystery of the Mona Lisa is not in her smile, but in the ingredients Da Vinci used to paint her

A group of French analysts suggest that the Renaissance painter, who liked to experiment, used a mixture of oil with lead oxide for the first layer of La Gioconda

Leonardo da Vinci tended to experiment in each of his works, not only with composition techniques, but also with the materials he used. To paint the Mona Lisa, his most famous masterpiece, it is likely that the artist used a unique mixture of lead oil in the preliminary layer. A group of French scientists came to this conclusion when they found plumbonacrite in a mini-fragment of the celebrated canvas. The presence of this mineral, the use of which was unusual at the time, suggests that the Renaissance genius tried to innovate by applying a thick mixture on the board on which he immortally enshrined La Gioconda.

The research, published Wednesday in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, “provides new information about the palette” used by Da Vinci, says Victor González, one of the authors of the study. The findings can be “useful for the understanding and preservation of his paintings,” adds the French National Center for Scientific Research analyst. The European Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (ESRF), the Louvre Museum, and the French Ministry of Culture also participated in the study.

Da Vinci, a great polymath who had the ability to combine art and science in the 16th century, left behind many manuscripts in which he developed his multiple sources of interest, such as engineering or architecture. But as the study highlights, “he left few clues about the materials used in his painting.” Nevertheless, scientists agree on his taste for experimentation. In each of his paintings, the research adds, “the composition of the layers is different, as are the materials used.”

A tiny sample, but a lot of information

The tiny fragment analyzed, which corresponds to the first layer that the artist applied on the famous poplar wood panel, provides key information. It measures less than 100 microns — one micron corresponds to one thousandth of a millimeter — and was on the upper right side of the painting that hundreds of people flock to see every day at the Louvre in Paris.

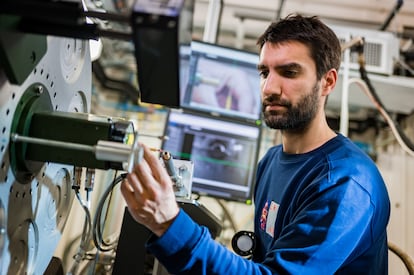

To analyze this small sample, protected between two sheets of glass, the team used the synchrotron, a kind of giant microscope located in the city of Grenoble. In the laboratory, they also applied infrared analysis.

The results revealed the presence of a unique lead oil mixture, one that is very different from what is usually seen in oil paintings of the period. “We detected by surprise a compound called plumbonacrite,” González says. Da Vinci did not use it as a pigment and it was not part of his palette, the researcher adds.

On the contrary, the substance was formed after chemical reactions in the paint itself, so it implies the presence of another compound. The researchers believe that this is lead oxide. In other words: to paint the first layer of the Mona Lisa, Da Vinci would have mixed his oil with lead oxide (litharge), a mixture with which a creamy, paste-like consistency is obtained.

There are several clues to support this hypothesis, explains Marine Cotte, co-author of the study who works at the ESRF in Grenoble. In 2019, plumbonacrite was detected in the paintings of Rembrandt, the 17th century Dutch master. In his case, he used it for impasto on his canvases, which accentuated the feeling of chiaroscuro. “Rembrandt put us on the trail,” the researcher notes. “We thought it was worth reanalyzing the paintings we were working with to see if they didn’t also contain” the same compound, she explains.

‘Last Supper’ and manuscripts as clues

But what really provided the biggest clues were the results of a parallel study that was carried out on samples of The Last Supper, the mural painted by Da Vinci between 1495 and 1498 — before La Gioconda — in the refectory of the Santa Maria delle Grazie convent in Milan.

In addition to finding plumbonacrite in the samples, the researchers also found undissolved particles of lead oxide. “It must be said that for La Gioconda we only analyzed a very small sample. We might have found [lead oxide] in another sample,” Cotte notes.

In search of further clues, the researchers decided to dive into the artist’s manuscripts, which are available online. It wasn’t an easy task. The language employed by Da Vinci is not the same as that of today, and painting terms differ from chemistry terms.

After a long search, they found a page in the Codex Arundel where lead oxide [letargirio di piombo, in the manuscript] was mentioned. Only the context in which it was used was not painting, but pharmaceuticals. “We think that if he used it for remedies, it is likely that he also used it for painting,” Cotte explains.

In addition to confirming this hypothesis, further questions remain. It is not known if plumbonacrite is present in the whole canvas, but the study undoubtedly provides new elements to understand the recipes employed by Da Vinci and the evolution of his paintings over time.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition