In 1997, for the first time, the American Film Institute (created by President Lyndon Johnson, founded by trustees like Sidney Poitier, Gregory Peck, and Francis Ford Coppola, currently consisting of famous filmmakers and less-famous historians, curators, and critics) published and promoted a list of canonical films, partly through a series of CBS specials that aired in 1998, 1999, and 2000. In none of these CBS specials did any narrator or interviewee mention that the list featured zero female directors and zero directors of color.

The AFI would go on to publish many other “Top 100” lists and an updated Top 100, but this first list serves as a helpful introduction to the American canon, or the films that probably most influenced previous generations of American audiences and filmmakers. This is presented chronologically partly to tell the most basic, entry-level “story” of American cinema. Later lists complicate the story.

~

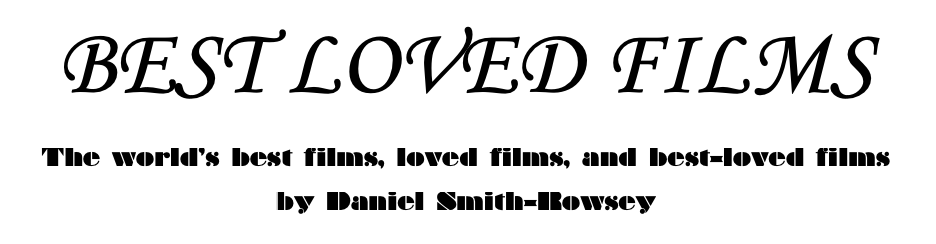

A1. The Birth of a Nation (Griffith, 1915) BO clip imdb LB RT trailer wiki

stream on YouTube watch analysis by Briggs read analysis by Dirks listen to my podcast

“Dare we dream of a golden day when the bestial War shall rule no more.”

In 1914 Griffith saw an Italian epic feature film called Cabiria that included shots from one of the first “dolly cameras,” or a camera mounted on sticks on wheels on a track. Griffith borrowed the technique for his own first epic feature. While the source novel of this feature, The Klansman, more or less begins in 1865, Griffith expanded the canvas to include the pre-war period and the war itself. In the early 19teens, fleeing lawsuits from Thomas Edison and seeking year-round amicable weather, much of the film industry had moved from New York to Los Angeles, and Griffith also took advantage of this to expand his canvas, repurposing the then-unpopulated San Fernando Valley as a Civil War battlefield.

The film’s plot was about two sets of star-crossed lovers, separated because of the war; one fragile white woman is chased by a lustful brutish black man and kills herself over a cliff rather than surrender to him, while another such woman, along with her family, are only saved from violent black people at the last minute by the newly minted, horse-riding Ku Klux Klan. Outside theaters, the film was indeed promoted by men in pointed white hoods astride white-clothed horses. Speaking of publicity, Griffith may have hoped that some would come from the friendship between the source novel’s author, Thomas Dixon, and President Woodrow Wilson, and Griffith got that publicity when Wilson called it “history written with lightning.” Griffith’s film may have been set a half-century in the past, but as it became America’s first blockbuster, it solidified Lost Cause mythology for a new century, successfully revived the then-moribund Ku Klux Klan, and accelerated a terrible period of lynching and anti-black violence.

Why, then, did the American Film Institute include this film on its 1997 list? We might ask the same of Roger Ebert, who was for years the only visible white man in the audience at the annual NAACP awards; the Birth of a Nation was one of 370 movies on Ebert’s Great Movies list through Ebert’s untimely death in 2013. The reasons are probably similar; while Griffith’s ideology was reprehensible, the film demonstrated amazing possibilities for effective melodrama. Prior to The Birth of a Nation, American films were mostly chases, capers, zany comedies, and serialized adventures that had recently been dubbed “cliffhangers.” Griffith synthesized the best elements of these into a 3 hour experience that was, if nothing else, heavy, eliciting waves of complex audience responses comparable only to literature or theater.

Influenced by: Lost Cause mythology, Reconstruction-era racism, The Great Train Robbery (1903), the dolly-shots of Cabiria (1914), a decade of shorts about chases and evolving cinematic conventions

Influenced: The American film industry; prompted production companies to move to Hollywood

~

A2. The Gold Rush (Chaplin, 1925) BO clip imdb LB RT trailer wiki

stream on YouTube watch analysis by Ouedraogo read analysis by Sante listen to my podcast

“I must have food!”

By 1925, the year he released The Gold Rush, Charlie Chaplin was probably the most famous person in the world, something that before Chaplin one could have only said of writer-artists or politician-leaders. This meant that Chaplin could insist on, and receive, control of every aspect of his films, right down to off-camera performances of the roles that his hired actors were then expected to imitate perfectly.

The Gold Rush is about a Lone Prospector, the Tramp persona, searching for gold in Alaska during the Klondike Gold Rush at the end of the 19th century. He meets a burly Big Jim who has found gold and the two of them get trapped by a blizzard in the cabin of a third, who is a murderous criminal. With an exquisite balance of pathos and slapstick, hijinks ensue, including some of the most famous of the Tramp’s career: hunger makes one man hallucinate the Tramp as a chicken, the Tramp pretends fork-skewered potatoes are dancing feet, and a cabin teeters off a snowy cliff’s edge.

The film is hilarious, exhilarating, and emotionally satisfying, while maintaining the general critique of widespread poverty and free-market orthodoxy that the Tramp character usually implied. It is often named as the best comedy of a decade known for comedies, the 1920s. Chaplin said at the time that it was the film that he hoped he’d be remembered for. At the time he was becoming known for something else. Not only was The Gold Rush not filmed in Alaska, its elaborate Klondike sets built on Hollywood backlots, Chaplin himself traveled to Mexico during production…to avoid being charged with statutory rape. Chaplin had a history of trying to court teenage actresses, and at the age of 35, Chaplin impregnated the 16-year-old Lita Grey, whom he had cast as the Tramp’s love interest in The Gold Rush. Grey’s pregnancy meant losing the role and gaining a husband during a quick trip to Mexico. After Grey gave birth to two sons by Chaplin, their marriage became very unhappy, and in 1927 her divorce application leaked to the press, including her accusing him of having “perverted sexual desires.” Religious groups called for Chaplin’s films to be banned, and Chaplin wound up paying Grey the largest cash settlement in American history up to that point – 600 thousand dollars. This site does not focus on salacious gossip, but at this point, no one should be talking about Chaplin without mentioning his pedophilia.

Influenced by: vaudeville, Keystone films, Harold Lloyd, Buster Keaton

Influenced: Chaplin was the world’s first superstar, validating Hollywood and Anglo-American values

~

A3. The Jazz Singer (Crosland, 1927) BO clip imdb LB RT trailer wiki

stream on amazon watch analysis by 100yearsofcinema read analysis by Fossaceca listen to my podcast

“Wait a minute, wait a minute. You ain’t heard nothin’ yet.”

The Jazz Singer is a thinly veiled biographical story of its star, Al Jolson, who plays Jakie Rabinowitz, whose desire to sing then-risqué jazz puts him at odds against his father, a very traditional Jewish cantor. In fact, this story centralized themes of the biographies of many of the leading studio heads, like Louis B. Mayer of MGM, Harry Cohn of Columbia, Carl Laemmle of Universal, Adolph Zukor of Paramount, and Jack and Harry Warner of the Jazz Singer’s studio, Warner Bros. These men almost never discussed it or made films about it, but they too were first-generation Jewish Americans whose parents initially disapproved of their choices to make careers in entertainment. And they, like Jakie Rabinowitz, were not above career advancement through exploiting the images of African-Americans.

Near the end of The Jazz Singer, Jakie burns a cork, applies the burnt cork to his face, and comes on stage in blackface to sing “Mammy” to his still-doting mother. This was racist, yes, but not the same sort of racism practiced by D.W. Griffith making The Birth of a Nation when he put white actors in blackface when they played black people touching white people. Jakie in The Jazz Singer is practicing a complicated cultural appropriation, in which he consciously borrows African-American tropes to indicate his own marginalized group’s solidarity with black people against the dominant white culture. Before you judge Jakie, before you say that any kind of racism is evil, consider your own forms of cultural appropriation, whether they involve cooking another culture’s food, speaking in another culture’s idiom, or wearing another culture’s clothes or jewelry or symbols. Many have compared the story of 8 Mile to the story of The Jazz Singer; in 8 Mile, Rabbit, loosely based on and played by Eminem, a demonstrate his white working-class solidarity with black struggles by adopting certain aspects of African-American hip-hop and culture. Most persons of color know that most white people have histories of both racism and tolerance. Three years before The Jazz Singer, George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue” brought jazz to the highest levels of prestige and respectability…but was only performed by white people, whitewashing an art form pioneered by black people like Jelly Roll Morton and Louis Armstrong. The film was arguably less racist than that; at least Jakie acknowledged his betters.

Influenced by: The Harlem Renaissance, immigrant/assimilation stories

Influenced: Wasn’t the first sound film but certainly inspired Hollywood’s sea change from silent to sound; Classical Hollywood, especially the musicals/hybridity of the 1930s

~

A4. All Quiet on the Western Front (Milestone, 1930) BO clip imdb LB RT trailer wiki stream on amazon watch analysis by DEPFilms read analysis by Bauer listen to my podcast

“You’re going to be soldiers – and that’s all.”

What did Hitler hate so much about All Quiet on the Western Front that he moved to ban it? In a word, pacifism. The book, and its 1930 film, are about young men conscripted to fight in World War I who quickly become disillusioned with the conflict. All Quiet on the Western Front was unsentimental and full of wide sweeping shots that Steven Spielberg would later credit as partial inspiration for Saving Private Ryan. In its own time the film became known as nothing less than America’s first great sound film, even if it was about German pacifists – of course played by American actors.

All Quiet on the Western Front was directed by a Russian-born American named Lewis Milestone. His surname, Milestone, is absolutely apropos of All Quiet on the Western Front, although in his career of about 50 films, he never quite made another equivalent milestone. As he came to the end of his life 50 years after All Quiet, Milestone begged Universal Studios to restore the truncated release version to its full length of 153 minutes. They ignored him, and he died in 1980. Twenty years later, after DVDs became popular, after the AFI CBS specials helped increase interest in the film, Universal did restore the footage, and that is generally the epic we see today.

Scholars have credited Remarque with creating a new subgenre, that of the plain-spoken confessional war journal novel, and the film was likewise a new kind of sound cinema that arrived with excellent timing. The Academy Awards had only been founded the year before, in 1929, and most of those first awards went to films that had actually been in theaters for more than a year, like Wings and Sunrise. Think of the context: before Birth of a Nation, movies were generally considered cheap escapist fare, comparable to how videos from famous YouTubers are perceived today. Even as studio heads wanted to convince the press that their films were award-worthy, they were spending more money promoting frothy musicals like The Broadway Melody, which won Best Picture at the second Academy Awards. By the time of those awards, in 1930, Hollywood seemed to be producing only cheap glitzy musicals; released into the 1930 marketplace, All Quiet on the Western Front was a major contrast, the kind of capital-A art that the studios wanted to show they could also make. And sure enough, when Netflix remade the same story more than 90 years later, this time actually in German, it surprised many by hauling in four Oscars.

Influenced by: then-common feelings about war; new sound practices

Influenced: demonstrated new possibilities for dramatic sound films

~

A5. City Lights (Chaplin, 1931) BO clip imdb LB RT trailer wiki

stream on YouTube watch analysis by Stuckmann read analysis by Giddins listen to my podcast

“I’m cured! You’re my friend for life.”

AFI’s top romantic comedy is esteemed partly because it represents Chaplin using his unusual power to thumb his nose at new industrial imperatives regarding sound, although this was Chaplin’s first time contributing to his own score; some have read the Tramp’s blind love interest as representing Chaplin’s mother, others see her as the studio system hearing but not seeing the big picture

In City Lights, released in 1931 and directed by Charles Chaplin, Chaplin’s homeless Tramp meets and falls in love with a blind woman, then works to get her the money for an expensive blindness-curing operation by a Viennese doctor. The movie involves a lot more shenanigans, playing on Chaplin’s favorite theme of the thin line between indigence and independence. The blind woman sells flowers in the street, has trouble paying rent, and because of a misunderstanding believes Chaplin’s character to be wealthy. As with Chaplin’s The Kid from ten years earlier, audiences warm to the sight of a poor wastrel helping a person even poorer than he is. City Lights also finishes what the Kid started in terms of successfully marrying pathos to slapstick, pain to pleasure, only to finish with a renewed appreciation for both. Without giving away exactly what happens, the final scene of the two lovers finally understanding each other is one of the most poignant and beautiful scenes ever put on film.

And…it comes at the end of a silent film, something that by 1931 only Charlie Chaplin could or would have even tried to get away with. In the years since The Jazz Singer the studios spent every dollar they had, and then some, to convert their theaters to a sound-on-celluloid system that was better and more expensive than The Jazz Singer’s initial sound-on-disk system. The studios had only just completed converting to sound when the big economic crash happened in October 1929; all at once, the industry suddenly became more risk-averse and more hostile to female screenwriters, something we’ll discuss in another podcast. Many lamented the change from silent to sound, talking about a lost artistry that the more vulgar, relentlessly representative “talkies” had made impossible. Nonetheless, by 1931, every other major director and actor had made a sound film…except Chaplin.

Charles Chaplin had his own crash, a year before the stock market’s, with the troubled production and release of The Circus in 1928, not to mention the death of his mother as well as ongoing rumors about his deviant preferences. Chaplin also worried, not without reason, that sound would ruin the magic of the Tramp. Chaplin spent a year working on the script for City Lights and another year shooting it, with an eventual shooting ratio that may have been unprecedented at the time for a feature: 39 to 1, meaning 39 feet of film shot for every 1 foot used. In other words, Chaplin was even more perfectionist than usual, going so far as to compose his film’s music for the first time. He was unhappy with dozens of actresses who auditioned to play his love interest, and finally chose Virginia Cherrill, a bathing beauty, partly because with her natural near-sightedness she was plausibly blind on film. But then her first scene took months to shoot because of Chaplin’s unhappiness with her performance. Months later, again frustrated, Chaplin fired Cherrill, hired Georgia Hale, who played his love interest in The Gold Rush, and then decided that the reshoots would be too expensive. Cherrill demanded and received a raise; she and Chaplin generally couldn’t stand each other.This goes to show you the distance between offscreen reality and onscreen fiction; from the day of its premiere, attended by guest of honor Albert Einstein, the film was a smash hit. The film is also now usually cited as the best romantic comedy ever made. Chaplin later named it as his favorite, updating his comment about The Gold Rush. Sight and Sound’s first list of greatest films called it the second-best movie, period; it has been considered among the best motion pictures by figures like Orson Welles, Stanley Kubrick, Federico Fellini, and Woody Allen.

Influenced by: vaudeville, other “Sweet Innocent” tales, The Circus (1928)

Influenced: Chaplin and Keaton were proto-blockbuster-ists, blending comedy, pathos, and broad action scenes

~

A6. Frankenstein (Whale, 1931) BO clip imdb LB RT trailer wiki

stream on amazon watch analysis by Shives read analysis by Hood listen to my podcast

“I think it will thrill you. It may shock you. It might even horrify you.”

If one begins feature-film history with The Birth of a Nation in 1915, one could begin the history of Anglo-American horror and science fiction exactly a century earlier, with the eruption of Mount Tambora in 1815 that led to Europe’s fabled “year without a summer” in 1816 and the gloom that settled over a group of young writers, including the 18-year-old daughter of feminist pioneer Mary Wollstonecraft. That summer, many decades before Stoker created Dracula, Mary Shelley created life that is somehow no less real for being fake. Shelley wrote the novel Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus, about a scientist who combines dead human parts with some metal parts into a living, human-like creature, who then rebels against his master; all horror and science fiction in the English-speaking world has flowed from Shelley’s original creation.

More than a century later, in 1931, Carl Laemmle wasn’t trying to remake his Universal Studios into the home of horror; he merely wanted to reuse the sets from Dracula to create another Dracula-sized hit. The original script turned Frankenstein’s monster into such a lumbering brute that Bela Lugosi, star of Dracula, refused to play him. But when director James Whale took over the project, he revived the monster’s soul as part of hewing closer to Shelley’s novel. Whale used the extant castle set, but added more torches and more wood to the doorframes for a less Gothic, more primal feeling that also gave the monster more stuff to destroy. Whale and his set designer Kenneth Strickfaden also borrowed from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis to create Frankenstein’s laboratory, complete with coiled glass tubes, humming batteries, and sparks flying over wooden palettes, pioneering a soon-to-be-indispensable set of motifs that would eventually be called “raygun gothic.”

Perhaps Whale’s greatest burst of creativity, like Frankenstein’s, went into the monster himself. Departing from the novel, Whale added neck bolts, a haircut that made his head look square, and green skin, even though the film would obviously be filmed in black-and-white. Why the verdant epidermis? It is possible that Whale made the monster’s skin green to mark him as more of an outcast, a deviant, a person rejected by society on face value. Of the directors discussed on this list,, James Whale is the first that we know of to be anything but a white straight male: Whale was gay, but in the closet, which is the subject of the 1998 film Gods and Monsters in which Ian McKellen won an Oscar nomination for playing Whale. Perhaps Whale and the actor who played the monster, Boris Karloff, meant for the monster’s marginalization to symbolize the marginalization of other groups; different viewers and readers have read the film and book in different ways.

We do know that Whale insisted on scenes from the novel that were disturbing enough to earn the film a first-minute disclaimer that includes the words “I think it will thrill you. It may shock you. It might even horrify you.” These included two scenes that were removed from prints after 1934, after the Hays Code came into full effect, one in which Henry Frankenstein says “Now I know what it feels like to BE God!” and another in which (spoiler alert) the monster throws a small girl into a lake, causing the town to pick up torches and riot against him. During the film’s release in late 1931, some U.S. states and later some foreign countries insisted on several cuts or just refused to screen the film altogether. Nonetheless, Frankenstein became a sizable hit. Based on that and Dracula, Universal Studios did remake itself into the home of horror, with sequels for Dracula and Frankenstein as well as new films planned for the likes of the Wolfman, the Mummy, and the Invisible Man.

Influenced by: greenlit after Dracula was a hit; German Expressionism, shadows and fog

Influenced: raygun gothic; a world of B-movies; man-machine discussions; other-ing

~

A7. King Kong (Cooper, Schoedsack, 1933) BO clip imdb LB RT trailer wiki

stream on amazon watch analysis by cinematicvenom read analysis by Haver listen to my podcast

“No, it wasn’t the airplanes. It was Beauty killed the Beast.”

In 1931, a young David O. Selznick at RKO Pictures hired Merian C. Cooper to make feature films that would resemble the documentaries that Cooper had made with his producer-director partner Ernest Schoedsack, like Chang and Rango, which featured monkeys in jungles sometimes threatening humans. A racist mockumentary film called Ingagi, which implied that black women and gorillas had procreated, was a 1930 hit that proved that apes plus vulnerable women equaled profits. Cooper and Schoedsack began a film they called The Most Dangerous Game, building an enormous jungle set and casting actors that would play humans being hunted by monkeys. Cooper also looked at footage from another RKO film then in production, called Creation, about a group of travelers shipwrecked on an island of dinosaurs. Cooper, along with Selznick and RKO, decided that neither project really worked but…and just stay with me for a minute here…what if you combined them?

Combining them meant creating a gorilla big enough to fight with dinosaurs, which led to another idea: wouldn’t such a monster be any American zoo’s most prized attraction? One issue with stories like The Most Dangerous Game and Creation is that they took place in remote jungles; why not find a way to threaten Americans where they lived? And in that case, why not underline the contrast between savagery and civilization by bringing the story right up to the minute, with a climactic scene at the brand-new symbol of American progress and ingenuity, the Empire State Building, and an expedition and extraction storyline motivated by none other than avaricious, sensationalist Hollywood filmmakers? The Depression-starved Ann Darrow character could almost be read as a proxy for the audiences that surprisingly showed up for Dracula and Frankenstein; Ann is so desperate and fearful, she’s willing to pay to scream. Someone somewhere may have worried that a story with so many contemporary references might have eventually seemed too dated, too locked in 1933; but the eventual result, King Kong, turned out to be a timeless inspiration for countless other films.

King Kong also drew inspiration, and staff, from a 1925 silent film called The Lost World, based on Arthur Conan Doyle’s 1912 novel of the same name. It featured Doyle himself in a short prologue in which he calls the film’s hero, Professor Challenger, his favorite of his own creations, even above Sherlock Holmes. In the movie, from which Steven Spielberg later appropriated the name and plot, Professor Challenger and his team battle dinosaurs, which were rendered by a brand-new process later called stop-motion animation. Basically, the effects team shot a clay figurine onto a frame image of actors, and then stopped, moved the figurine a tiny bit, and then shot the figurine onto the next frame of footage. If you’re lucky and good, you could maybe do one such shot every five minutes, which means, if the film has been shot at 24 frames per second, it would take you two hours to get one second’s worth of dinosaur on film. King Kong’s effects department wound up getting more than 15 minutes of stop-motion animation into their film, led by The Lost World’s Willis O’Brien. The film also relied heavily on rear-screen projection, in which actors walk in front of pre-shot footage, as well as using stop-motion alongside matte paintings and miniatures, and in so doing King Kong set the standard for the modern special-effects-driven blockbuster.

While Frankenstein features almost no music, King Kong pioneered cinematic music, being the first film to feature more than an hour of original, never-before-heard music. Max Steiner composed different themes for different characters, inspiring everyone from Prokofiev, who wrote Peter and the Wolf shortly after seeing King Kong, to John Williams and beyond. Even if studios like MGM and Paramount would never make a film like King Kong, they were happy to hire Steiner, who became the foremost film composer of his generation.

The script for King Kong was almost sui generis, a sort of 20th-century Beauty and the Beast allegory about the destructive powers of both love and civilization. King Kong was rewritten by Schoedsack’s wife, Ruth Rose, who cut much of the plodding exposition and made the three lead humans, Denham, Driscoll, and Darrow, into humorous, self-aware versions of Cooper, Schoedsack, and herself, respectively. The story was arguably its own kind of Frankenstein’s monster, combining the best and shortened parts of the discarded movies into a plot that many have read as commentary on colonialism and slavery importation. The location of Skull Island is vaguely part of Western Oceania, but the tribal rituals and the tribesmen that we first see on Skull Island seem entirely African. If King Kong represents, consciously or unconsciously, a captured brown slave, what are we to make of his obsession with the white blonde often-screaming Ann Darrow? Feel free to go down the rabbit hole of internet theories; perhaps that’s appropriate to the rabbit-fur on the stop-motion models for Kong. (No actor ever wore a gorilla suit in the original film.) Martin Scorsese would later say that the animal fur combined with O’Brien’s movements “gave him a soul.” It may have been beauty killed the beast, but it was the filmmakers who arguably created the first American Hollywood epic myth. Dracula and Frankenstein are European stories; King Kong is closer to a classic American immigrant; together, the three of them set the standard for all future creature features, and much horror and science fiction.

Influenced by: nature expedition documentaries, The Lost World (1925), Ingagi (1930), Rango (1931), Universal horror pictures

Influenced: the Willis O’Brien/Ray Harryhausen school of effects; large-scale horror/fantasy/sci-fi films

~

A8. Duck Soup (McCarey, 1933) BO clip imdb LB RT trailer wiki

stream on amazon watch analysis by Jozic&Friesenhen read analysis by Snider listen to my podcast

“..and remember, while you’re out there risking life and limb through shot and shell, we’ll be in here thinking what a sucker you are.”

Duck Soup wasn’t easy to make, which is ironic, because duck soup then meant something easy to do, although Groucho also used the title to imply that if the Marx Brothers cooked it, “you’ll duck soup for the rest of your life.” In mid-1932, a new Marx Brothers film was announced, to be directed by the already-legendary Ernst Lubitsch…but at the height of the Depression, the Marx Brothers’ negotiations with Paramount over contract renewal dragged on for months, into the Roosevelt presidency. This arguably did not hurt the final product and may have even helped it; the film wound up recycling many of the same gags that Groucho and Chico performed on a radio show that winter.

Thanks to the rise of Roosevelt, Hitler, and Mussolini, politics was in the air, and the time seemed right for a comedy that lambasted politicians, dictators, fascists, generals, and authoritarians. As it turned out, audiences in 1933 didn’t particularly appreciate Duck Soup, but later generations declared it the best Marx Brothers’ film. In the plot, Rufus T. Firefly, played by Groucho, is appointed leader of Freedonia, and he proceeds to declare war on Syldavia, a country that has sent two spies, Chicolini, played by Chico, and Pinky, played by Harpo. Some people see Harpo as a bridge to silent films, because he never spoke and relied upon pantomime-based humor. But any Marx Brothers film is stuffed to the rafters with silly verbal jokes and anarchic tomfoolery, and this is especially true of Duck Soup, considering it eschews the melodramatic songs and romantic subplots that slow down some of their films.

The dialogue was usually something like Groucho saying, “Will you marry me? Did he leave you any money? Answer the second question first.” The woman was stuck replying “He left me his entire fortune” to which Groucho would answer, “Can’t you see what I’m trying to tell you? I love you!” Everything, everything was played for laughs and criticism, often self-criticism. The style and tone was adopted by Warner Bros. cartoons, and indeed some of Bugs Bunny’s best bits are salutes to Duck Soup, including “you realize this means war” and a scene where a character pretends to be the reflection in a mirror. The Marx Brothers didn’t originate either of these, but they made them funny, they made a lot of more original bits funny, and their influence would be strongest over Monty Python, the Zucker-Abrahams-Zucker team, Woody Allen, and anyone else who would do anything for a cheap laugh. The Marx Brothers wound up making a few more films classic films with MGM, but running out of steam during the war years…when Bugs Bunny came along to pick up the torch.

Influenced by: vaudeville, Chaplin, Laurel and Hardy

Influenced: Abbott and Costello, The Three Stooges, Woody Allen, the “Borscht Belt”

~

A9. It Happened One Night (Capra, 1934) BO clip imdb LB RT trailer wiki

stream on amazon watch analysis by 100yearsofcinema read analysis by Nehme listen to my podcast

“You see that? The walls of Jericho.”

In some ways Capra invented, or minted, the “screwball comedy” with this road-trip story of a

After years of basically reacting to the Depression with escapism, King Kong and the recent Gold Diggers films, among other hits, suggested audiences were ready to integrate humor and class struggles. Into this atmosphere stepped a first-generation Italian-American director named Frank Capra who had acquired a somewhat unremarkable short story written by a journalist named Samuel Hopkins Adams.

Adams’ story, Night Bus, promised to be the kind of film you could make if you weren’t making King Kong, a quickie, apparently just another widget on the assembly line. It was even a little lower-rent than many of those, as evidenced by the fact that MGM and Paramount didn’t want it. Night Bus fell to Columbia, whose tight-fisted chief, Harry Cohn, was still struggling to forge a positive brand for his studio. Cohn was notoriously the biggest misogynist in a town full of misogynists, so it’s a little ironic that the film that saved and refocused his studio is, on the chronologically ordered AFI Top 100, the first film of nine with a woman as lead or co-lead. That, by the way, is an outrage, particularly considering that more than half of produced Hollywood screenplays before 1930 were written by women. But let’s be clear: as incarnated by Claudette Colbert, the role of spoiled heiress Ellie Andrews takes a full and wry command of the screen for two hours, even if her back-and-forth with petulant reporter Peter Warne, played by Clark Gable, must be and is a sparring of equals, a pas de deux of comeuppances, a seesawing banter-tossing power-swapping courtship that would provide a key template for what became known as the screwball comedy.

Strange to think that in the Depression no previous film had so successfully matched an authority-distrusting working-class man with an authority-distrusting upper-class woman, but this film is in equal conversation with romance and class struggles. The plot here is that Ellen is running away from her father’s insistence that she annul her marriage, while a recently fired Peter is trying to rescue his job by getting an exclusive with Ellie. The undershirt sales plunged because of Gable’s conspicuous tank-top under his dress shirt; Bugs’ carrots came from a scene when Peter proves to Ellie that they don’t need money for food because they can eat carrots out of the ground. Peter is still chewing on them as the film segues into its most famous scene, when Peter attempts to hitchhike for them a ride, fails at several thumb movements, and laughs when Ellie says she can do better. Ellie says “I’ll stop a car, and I won’t use my thumb,” sees a male driver approaching, lifts her skirt a bit, and then she and Peter watch as the driver slams on his brakes.

Nehme writes that the film was made during, and straddles, the two eras of 1930s filmmaking, both the pre-Code period when sex was seen as normal, and the post-Code era of restraint, as represented by discreet lighting and the recurrent motif of the walls of Jericho, which is the name Pete gives to the blanket he hangs on a string between their single beds in the hotel rooms they share. The title Night Bus sounded a bit naughty, and it was redubbed with a title that traded accuracy for wholesomeness, considering Ellie and Peter’s weeklong road trip adventure, and that title was It Happened One Night. In retrospect, the one night that It Happened feels like the evening in 1935 when the film became the first-ever film to quote-unquote sweep the Academy Awards, winning Best Actress, Actor, Script, Director, and Picture.

Influenced by: Capra’s upbringing as first-generation Italian-American; literate comedy

Influenced: screwball comedy, Bugs Bunny (carrot chewing was based on the lead male character)

~

A10. Mutiny on the Bounty (Lloyd, 1935) BO clip imdb LB RT trailer wiki

stream on amazon watch analysis by CSP read analysis by Dirks listen to my podcast

“Christian lost, too, milord. God knows he’s judged himself more harshly than you could judge him.”

Under the guidance of chief mogul Louis B. Mayer and his crack lieutenant Irving G. Thalberg, MGM was the studio of studios, the richest, most glamorous, and most sophisticated in town, known for extravagant musicals, witty comedies, heated melodramas, and as its press releases said, “more stars than there are in heaven.” One of those stars was Clark Gable, whom Mayer had only loaned to Columbia for It Happened One Night as a sort of punishment because Gable kept asking for more money; the joke was on Mayer when Gable won an Academy Award. Mayer and Thalberg found a way to get even with their contract player, making him shave his beloved mustache for the sake of historical accuracy in a story in which Gable would play, well, a crack lieutenant opposing an overbearing captain. Instead of an opinionated artist like Capra, Mayer hired the more craftsmanlike Frank Lloyd to direct MGM’s adaptation of Charles Nordhoff and James Norman Hall’s recent historical novel Mutiny on the Bounty.

The film’s story begins in 1787, an ocean away from the Philadelphia hall where some old white guys were then writing the U.S. Constitution. Over in London, a man who could have passed for a founding father, Captain Bligh, played by the estimable Charles Laughton, begins a two-year British naval expedition. Eagle-eyed viewers may see James Cagney in a boat in the background; Cagney was arguably the biggest star of the 1930s, but moonlit in one scene for MGM for nothing because he was then arguing about money with his own studio, Warner Bros. After the Bounty arrives in the South Pacific, Captain Bligh punishes recalcitrant crew members with keelhauling, water rationing, and corpse-flogging. When the men go ashore, a couple of lieutenants, including Gable’s character, Fletcher Christian, flirt with a couple of Tahitian women. Finally, the mutiny of the title occurs, and the previously reluctant Mr. Christian rallies his mutineers around establishing a more egalitarian paradise in Tahiti. The novel and movie took a lot of dramatic license with the 18thcentury events, but this last point was particularly egregious: the real Fletcher Christian treated native Tahitians like slaves. A Hays Code-governed MGM couldn’t show the so-called miscegenation of the white men and their native consorts, while later versions could and did, starring Marlon Brando, and later Mel Gibson, as the supposedly progressive Fletcher Christian. Unfortunately, no Hollywood version showed the truth that these ostensible rebels against British imperialism preserved their weapons and prejudices with the Tahitians, and so any sexual congress between white men and Tahitian women amounted to forced assault, or to drop the euphemism, rape.

The 1935 Mutiny on the Bounty clearly sympathizes with Mr. Christian against Captain Bligh, mirroring the real-life relationship less of Gable to anyone, and more to Irving Thalberg against his boss Louis B. Mayer. Thalberg was the person primarily responsible for MGM’s output being so much higher than any of its rival studios – almost one picture a week – but Mayer didn’t give bonuses for that. Thalberg successfully brought the Marx Brothers to MGM, but Thalberg generally preferred prestigious literary adaptations while his boss liked glitzy star showcases. Mutiny on the Bounty was the rare film they could both love, a big hit that also won the Academy Award for Best Picture. Six months after that victory, the fragile 37-year-old Thalberg caught pneumonia and died. Hollywood went into shock, with major stars openly weeping on sets; the best possible snapshot of 1930s Hollywood talent is the guest list at Thalberg’s funeral, at least until the 1939 premiere of Gone with the Wind, a film MGM could have made and didn’t. On the one hand, MGM after Thalberg mostly turned back to glitz and glamour; on the other hand, hits like Mutiny on the Bounty and the memory of Irving Thalberg spurred other studios to adapt more books in the late 1930s, leading to some all-time classics.

Influenced by: MGM moving good writers from Broadway to Hollywood

Influenced: more adaptations of prestige novels and Shakespeare

~

A11. Modern Times (Chaplin, 1936) BO clip imdb LB RT trailer wiki

stream on kanopy watch analysis by Uyeda read analysis by Eggert listen to my podcast

“Free? Can’t I stay a little longer? I’m so happy here.”

By 1936, if Chaplin was going to make a movie he wanted it to meet his standards, which meant that it had to be urgent, newly inspired, and assembled with his now-infamous perfectionism. For years, he made nothing. He was finally inspired during a conversation with Mahatma Gandhi whereby Gandhi claimed that modern technology was ruining workers’ lives.

By 1936, Chaplin was both a man for all times and a man out of time, or at least out of a different era, when pantomime and stunts mattered more than Marx Brothers-ish rapid-fire dialogue. Genuflecting to the skeptics, Chaplin wrote some sound-worthy dialogue and experimented with a few sound scenes – only to retreat to making a “silent” picture, although there were a lot of sound effects and even moments of voices. Most of the film was shot at the once-standard “silent speed” of 18 frames per second, and that meant that when projected, as it usually was, at the new standard of 24 frames per second, the action appeared a third again more frenetic. Modern Times might have been worth making just because of the brilliance of the title, a double entendre that referred to two Fordist assembly lines, the first being a Hollywood that the anachronistic Chaplin couldn’t quite conform to, the second seen onscreen as Chaplin’s Tramp falls into its gears in the film’s most famous scene.

Students of the clip of the Tramp in the gears are sometimes surprised to see that, about one film minute later, the Tramp playfully wears forearm-sized wrenches as earrings and chases down a young thin woman who happened to be on the factory floor. As she flees, the Tramp sees another woman and chases her the same way. It’s not clear why the Tramp bothers with this odd behavior. After and during many other misadventures, he falls in love with a poor barefoot woman the film calls “the gamin,” and together they dream of her in traditional domestic situations, for example wearing a frilly apron when he comes home from a dream job. The gamin was played by Chaplin’s then-real-life girlfriend Paulette Goddard, who was 25 when the film was made, but seems to be playing younger, considering she is pursued by the police department’s juvenile division. That said, the gamin is sneaky, fun, and resourceful, to the point of finding the couple a house, actually a one-room shack in which the Chaplin character somehow manages to sleep a room apart from the Gamin in some kind of…bike shed? The gamin’s general pluck, grit, verve and physicality was well beyond Chaplin’s previous onscreen paramours, and more comparable to that of women in the dominant comic genre of the time, the screwball comedy. One can summarize Modern Times by saying that the Tramp often falls into situations where he is unfairly blamed for some larger movement that Chaplin probably approves of, as when the Tramp is mistakenly arrested at a Communist demonstration, accidentally knocking escaping prisoners unconscious, or falsely claiming to have stolen bread that the hungry gamin has stolen. As the Gamin and the Tramp work to make it this crazy world, eventually he finds work as a singer/waiter, and when he loses the lyrics to a song, he rescues the situation with pantomime and gibberish, providing audiences the first-ever sound of the voice of Chaplin. This was Modern Times in a nutshell: a one-time-only just-enough gesture to the new era, seasoned with much of the old-time artistry. Critics have always loved Modern Times, as did later audiences, but the film’s box office was only pretty good, a fact that may be attributed to the film’s anachronistic nature, or perhaps its overtly anti-industrial politics, which in the context of 1936 were to the left even of President Roosevelt. Charlie Chaplin was both growing up and refusing to grow up.

Influenced by: the Depression; Chaplin’s adversarial relationship with sound

Influenced: Sartre, who named his journal after it; dozens of direct imitations, especially of the iconic assembly-line scene

~

A12. Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (Hand, 1937) BO clip imdb LB RT trailer wiki

stream on Disney+ watch analysis by Dinseyinhonesty read analysis by Randall listen to my podcast

“Hi ho, hi ho, it’s off to work we go.”

After years of frustrations with the polyopoly of moguls, especially Harry Cohn at Columbia, Disney knew he would never be satisfied until he made his own features. At the time, almost no Americans, and perhaps not Disney either, knew that any country had ever made a feature-length cartoon, so the project was rather risky, as though someone today were to announce the first 90-minute virtual-reality film to be released nationwide. People called the project “Disney’s folly.” MGM’s Louis B. Mayer told the media, “Who’d pay to see a fairy princess when they can see Joan Crawford’s boobs for the same price?”

First Disney went twice over budget, then triple over budget for a final, almost-unheard-of cost of about 1.5 million dollars. Walt Disney borrowed perfectionism, and some badly needed finishing funds, from his friend Charlie Chaplin. For this movie, everything had to be exactly right: the movements, the songs, the colors, the acting, the humor, especially the pathos. Finally, four days before Christmas 1937, Walt Disney sat in the back row of the Carthay Circle Theater in Los Angeles and watched as the first-ever large audience saw Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Disney later recalled the moment that he realized he would not have to be in debt for the rest of his life: when the dwarfs cry over what they think is the dead Snow White, Disney saw Clark Gable’s massive shoulders shaking from the front row. A live audience, including the town’s manliest man, was for the first time crying at a cartoon. On that yuletide evening, Disney did more than escape the fear of dying poor: he began a path to becoming the single most influential artist of the 20th century.

David Hand supervised the animators and is the credited director, but make no mistake, Walt Disney personally supervised and made final decisions on every part of Snow White’s three-year process. Snow White was a century-old Grimm’s Tale that became a Winthrop Ames play that became at least two silent movies, but in none of those incarnations did the dwarfs have distinct personalities; Walt Disney workshopped a few ideas with his staff before settling on the dwarfs you know. No doubt the dwarfs’ chief functions are humor and helping Snow White, but there’s an interesting case that they also resembled the studio moguls – Universal’s anemic Carl Laemmle as Sneezy, Fox’s catatonic William Fox as Sleepy, Columbia’s hostile Harry Cohn as Grumpy, the malapropism-making Samuel Goldwyn as Doc, and Paramount’s recalcitrant Adolph Zukor as Bashful. This reading makes sense if you, as most of his biographers do, think of Snow White as resembling the outsider underdog Walt Disney, with trust issues, a strong work ethic, a need to conquer the previous jealous generation, and an escape into fantasy as a remedy for harsh reality. This take sees the dwarfs as moguls who, as you know since you’ve seen the film, certainly help Snow White-slash-Disney but ultimately cannot save her. It may also be worth noting that Disney was a goyim and all the moguls were Jewish, and that the dwarfs conform to harmful Jewish stereotypes – short, large-nosed, and working as jewelers.

The metaphor is imperfect, though, and one could see Prince Charming as Disney, arriving at the end to take Snow White to his fairy-tale castle. Perhaps Snow White is simply young America, in unusual harmony with animals, with the witch representing an older, bitter generation that is obsessed with appearance. Neither of the film’s two women could be considered as free-spirited or laudable as pre-Code stars like Mae West or Greta Garbo. To reclaim status as the kingdom’s most beautiful woman, the witch is willing to make herself ugly – a possible comment on the shallowness of plastic surgery – while Snow White runs through a forest in high heels, cheerfully does domestic work for seven male slobs, and sings, as her song of aspiration, “Someday My Prince Will Come.” Joe Breen at the Hays Code office was no doubt thrilled that Disney projected as a heroine such a traditional, conservative vision of womanhood, and even more thrilled that the film became, by mid-1939, the highest-earning film of all time. It soon lost that particular honor, but all things considered, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs remains likely the most-seen film of all time.

Influenced by: Disney shorts, German fairy tales and, in forest shots, German Expressionism

Influenced: American animation toward features, fairy tales, broad characters, and conservative values

~

A13. Bringing Up Baby (Hawks, 1938) BO clip imdb LB RT trailer wiki

stream on amazon watch analysis by bandgeek8408 read analysis by O’Malley listen to my podcast

“Because I just went gay all of a sudden!”

David, a paleontologist played by Cary Grant, has several goals: acquiring the final bone of a brontosaurus, impressing a possible museum donor, preparing for his wedding the next day, and playing golf, the latter being interrupted by Susan, a rich heiress played by Katharine Hepburn, who meets David, confuses him for a zoologist, and insists on his help bringing a leopard up to her farm in Connecticut. This is why the film is called Bringing Up Baby – the mild-mannered leopard is named Baby, though the phrase then and now refers to child-rearing, and here functions as a sly way of implying that neither David nor Susan would do well raising an infant. Farcical shenanigans ensue as the smitten Susan finds one reason after another to delay David’s return to the city, including Susan’s dog burying David’s just-delivered prize dinosaur bone and confusing Baby with a more dangerous leopard. The dialogue is rapid-fire, the antics are zany, and all told, the motion picture is one of the most hilarious ever made.

Of historical interest is a moment when the wealthy donor, going by the delightful name Elizabeth Random, arrives and asks David why he is wearing a full negligee. Instead of saying the truth, which is that Susan has, ahem, misplaced his clothes, David retorts, “because I just went gay all of a sudden!” leaping into the air on the word gay. This was not in the script, not censored by the Hays Office, and never explained by the writers or Cary Grant or RKO. Perhaps Grant simply meant “happy,” or perhaps Grant hung out with people who knew things that most Americans would not learn for at least another three decades, after the Stonewall riots put the modern usage of “gay” in the mainstream media. Cross-dressing was clearly played here for gender-bending humor but was in no way unusual for a male star in 1938, no more unusual than a female star playing a scatterbrained heiress.

As Susan, Katharine Hepburn’s titanic steeliness is both deployed and subverted. Screenwriter Dudley Nichols tailor-made Susan to Hepburn’s personality, which he knew from an earlier film she had made directed by John Ford; Hepburn may have had an affair with Ford, and David’s glasses in Bringing Up Baby do resemble Ford’s. As for the director of Bringing Up Baby, Howard Hawks, he asked Hepburn, early in the filming, to tone down her “acting” and just be herself to better serve the comedy. The feminist takeaway here isn’t simple. One way of seeing Hepburn as Susan is a bravura, exhilarating performance of headstrong naivete. Another way of seeing Hepburn as Susan is a series of humiliations of a powerful woman. It’s hard to know which one audiences were rejecting when they didn’t turn up in large numbers for Bringing Up Baby, some of them apparently choosing to see Snow White again. For this failure, Hepburn was labeled box office poison, an honorific she only lost after The Philadelphia Story became a hit with Hepburn playing…a rather similar role. Perhaps Hepburn as Susan was just ahead of her time. Hawks attributed the failure of Bringing Up Baby to the notion that “There were no normal people in it. Everyone you met was a screwball.” To Hawks this seemed a miscalculation, but considering how later audiences embraced the film, we now see this aspect as ahead of its time.

Influenced by: Capra films, 1930s opulence; Much Ado About Nothing; As You Like It

Influenced: other screwball comedies; strong female characters and perhaps Manic Pixie Dream Girls

~

A14. Stagecoach (Ford, 1939) BO clip imdb LB RT trailer wiki

stream on criterion watch analysis by Paula read analysis by Punch listen to my podcast

“Yes, sir, she is a little bit savage, I think.”

Films like the Broncho Billy and Tom Mix serials, featuring a lot of white hat-wearing cowboys riding easily to the rescue, had considerably cheapened the western genre by the time Haycox’s story “The Stage to Lordsburg” appeared in 1937. Ford and Nichols saw in Haycox’s story a chance to pivot to something Depression-era audiences might appreciate, fiercely independent outcasts thrown together on a journey across unforgiving lands, to find or make a new America. Let Walt Disney have his Snow White and seven dwarfs; Ford and Nichols’ treacherous stagecoach ride would shove together a prostitute and seven rogues: a drunk doctor, a whisky salesman, a bitter Confederate “gentleman,” a shifty marshal, an angry guard, a pious blueblood, and a fugitive. John Ford hadn’t made a western since the silent era, and he didn’t want this one to look or feel anything he or anyone had done; he would use long shadows, moody lighting, and unprecedented location shooting in Monument Valley – in other words, an A-picture, not a low-budget B-picture. But no studio wanted to give Ford the money for an A-picture – after all, Ford hadn’t made a western since the silent era, and no one had made a particularly great one since.

Lucky for Ford that Chaplin and Griffith had founded United Artists two decades before, because United Artists could distribute a film from an independent producer willing to put up the money. That eventual producer, Walter Wanger, almost walked away over Ford’s insistence on a relatively unknown actor in the lead, but Wanger eventually agreed to finance the film, retitled Stagecoach, at about half the budget Ford wanted. That unknown actor, John Wayne, is actually terrific in Stagecoach as the Ringo Kid, a prison escapee who falls in love with the wrong woman while plotting revenge on the men who have killed his brothers. Here John Ford made a star of John Wayne, and the 24 films they eventually made together may represent the most successful and influential star-director partnership in American cinema.

At one stagecoach stop, the snobby blueblood woman and the Confederate veteran walk away in a huff from the lowly Ringo Kid and Dallas. Stagecoach is careful not to actually call Dallas a prostitute, but in the first scene a sneering Ladies Club leaves little doubt as to the reason they want Dallas out of their respectable town. Ringo joins the stage late, fails to learn Dallas’ reputation, and midway through the ride proposes marriage to her. No doubt Joseph Breen watched Stagecoach with bated breath to see what would become of their romance; the Production Code was clear that low virtue could never be rewarded. As Dallas, Claire Trevor acts for most of the film like she knows the Code all too well, certain that Ringo will leave her when they arrive at their destination and he learns who she really is. In the final scene (spoiler alert), Ringo accepts her as she is with a hug – the Code prevented a loving kiss to a prostitute – followed by the Marshal and the doctor surprising them by sending them both across the border as the credits roll. Technically, this sort of happily-ever-after might have been seen as rewarding vice, but perhaps Ford and Nichols were relying on Breen’s racial biases to see Mexico as the opposite of paradise. They got their seal.

The film became notorious for reifying other racial biases. At one stagecoach stop, the whiskey salesman sees an Apache woman and blurts to the Mexican man pouring him a drink that his apparent consort is a savage, and he replies, “Si, she is a little bit savage, I think.” He notes that her Apache status affords him protection against nearby Apache warriors just before she sings a heart-rending song. If the film had left off there, historians might have given Ford credit for relatively enlightened representation…but a later scene suggests that the “savage” scene merely set up a much cruder caricature. All along, the stage riders fear an Apache attack, and when it comes in a gangbusters setpiece, the aggressive Native Americans are rendered as faceless, honorless villains. Perhaps Ford didn’t mean to otherize Indians, or perhaps Ford was letting his Birth of a Nation flag fly. Indeed, the effects of the films were comparable. Stagecoach countered Hollywood’s many positive representations of indigenous people in the 20s and 30s, and repositioned Indians as savage bad guys at the same moment that the film brought the cinematic western into A-picture status over the following decades.

Influenced by: the Western genre from pulp fiction to 1930s relic

Influenced: most Westerns and many other notable films (Orson Welles said that to direct Citizen Kane, he watched Stagecoach 30 times)

~

A15. Wuthering Heights (Wyler, 1939) BO clip imdb LB RT trailer wiki

stream on amazon watch analysis by TCM read analysis by Massie listen to my podcast

“Do not leave me in this dark alone… I cannot live without my life, I cannot die without my soul.”

Emily Bronte’s only novel is about a rich English family in the 1770s, the Earnshaws, who meet a homeless boy, Heathcliff, and take him to live with them at Wuthering Heights. He and his peer Catherine often play on the nearby moors, kind of a field of large boulders, and the pair grow up and fall in love. Nonetheless, Catherine eventually chooses to marry a wealthy man named Edgar Linton. Heathcliff makes a fortune and returns to exact revenge on Catherine, partly by marrying Edgar’s sister Isabella. Catherine dies, partly of a broken heart, and literally haunts Wuthering Heights; in 1801, Catherine’s ghost frightens a young visitor, who then learns all this from the estate’s housekeeper in the novel’s framing device.

The film adaptation preserves all of this, but removes most of the novel’s second half on its way to changing Bronte’s meanings. In the novel’s second half, Heathcliff manipulates his and Isabella’s son into romance with Edgar and Catherine’s daughter, and if you’ve been paying attention you know that makes them first cousins, an entanglement the Production Code would not have looked favorably upon. Following the book, the film never explains Heathcliff’s sudden wealth, but onscreen this error seems more glaring, implying that any British person could easily become rich in the 1780s, missing the chance to suggest that Heathcliff may have done something immoral. The film’s Catherine is less spiteful and more wistful about her lost romance with Heathcliff, and on her death-bed she tells Heathcliff she will someday see him out on the moors. In a major departure from Bronte, in an ending that director William Wyler and the two principal actors refused to shoot, leaving producer Samuel Goldwyn to film it with body doubles, the new ghost of Heathcliff meets Catherine’s ghost on the moors, dressed as they were when young.

Bronte’s novel is about how avowing vengeance against a person hurts both people, and her structure is a spiral of spite, with Catherine’s ghost menacingly haunting Heathcliff even as he, in flashback, works against her and her daughter. The film’s ending suggests that Catherine only seems to be haunting Heathcliff out of love. One wonders how the ghost of Emily Bronte may have haunted this production. One wonders how different the film might have been if the lead creative team was something other than highly successful men; one wonders about the twin effects of the Code and the steady curtailment in the 1930s of female screenwriters paired with the steady rise of male Broadway playwrights like Ben Hecht. Also, the film might have better emphasized its points about “different stations” if it cast, as Heathcliff, someone who looked a little closer to Bronte’s description as “a little Lascar” and “dark-skinned gypsy in aspect.” The film’s Heathcliff, Laurence Olivier, only appears dark on the film’s poster. That said, Olivier is outstanding in the role, and working alongside strong actors like Merle Oberon and David Niven in shots assembled with Wyler and Toland’s scrupulous craftsmanship, Wuthering Heights often resembles a great film. The fog-strewn moors, actually craggy portions of Wildwood Regional Park near Los Angeles, successfully symbolize a certain repressed British character, wild and stony.

Influenced by: prestige novel adaptations of Austen, Thackeray, and the like

Influenced: made Laurence Olivier a star, who was then considered Hollywood’s best actor before Brando came along

~

A16. The Wizard of Oz (Fleming, 1939) BO clip imdb LB RT trailer wiki

stream on amazon watch analysis by CollativeLearning read analysis by Rushdie listen to my podcast

“With the thoughts I’d be thinkin’, I could be another Lincoln, if I only had a brain.”

Students are often surprised to learn that the 1939 version of The Wizard of Oz is the fourth filmed version of L. Frank Baum’s novel from 1900, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. What changed? In a word, commitment. Knowing full well that a rival was then making the extravagant Gone with the Wind, Louis B. Mayer and MGM strongly committed to Baum’s story, to the sets, to the actors, and to making new songs. After Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs succeeded beyond anyone’s expectations, Mayer searched for a similar property that he might adapt into a colorful live-action musical. Mayer found a wicked witch challenging a lost ingenue, her beloved animal friends, and dwarfs, ahem, munchkins. If Disney could make a small fortune with seven little people, Mayer would bring out more than a hundred of them.

Perhaps Mayer’s smartest move was to delegate the minutiae of production, as he had during the Thalberg years. The final decisions on The Wizard of Oz were apparently made by Mervyn LeRoy and Victor Fleming, although this is controversial amongst scholars; at least 11 writers worked on the script, and as Salman Rushdie put it, the various later claims to authorship bring the film close to what Rushdie called “ that will-o’-the-wisp of modern critical theory: the authorless text.” I cannot recommend Rushdie’s book-length essay on The Wizard of Oz highly enough; it should be the first book you give to skeptics who claim that any film analysis is worthless. Coming from a tradition of many gods, Rushdie marvels at the film’s “joyful and almost total secularism,” at a land where witches and a wizard are feared but not worshiped or sanctified. He credits the film’s “absence of higher values” for its successful, ahem, lionization of the loves, cares, and needs of humans and human-like characters. Rushdie’s biggest issue with the film is that if you travel from a parched, mean, black-and-white farmland to a full-color fairyland where almost everyone treats you like a princess, “there’s no place like home” seems almost atonal. I would counter that like a lot of films and fairy tales, The Wizard of Oz has specific appeals to diametrically opposed audiences, in this case to travelers and homebodies.

The Wizard of Oz is as close to an American fairy tale as anyone has come. Almost every other well-known fairy tale is set in Europe; many things about The Wizard of Oz derive from an idiosyncratically American imagination, not least its white girl reimagining and fast-befriending her neighbors as non-white persons. Henry Littlefield claimed that Baum’s readers of 1900 understood the story as a satire of the capital-P Populists, then at their apex as the most successful third party in U.S. History, with Dorothy-slash-Kansas signifying the epicenter of Populism, the Scarecrow as farmers, the Tin Man as manufacturers, the Cowardly Lion as their feckless sometimes-leader William Jennings Bryan, the Munchkins as, well, the little people of common American discourse, the yellow brick road as the suspicious gold standard leading to a Potemkin-village Emerald City led by a wizard, signifying industrial capitalism, who turns out to be humbug. He’s so humbug that he hangs a cheap Cross of Gold on the figure who famously said mankind would not be hung on a Cross of Gold, William Jennings…Lion.

Film viewers don’t really absorb much of this, but Bruno Bettleheim’s work on fairy tales shows that children sense subtexts about historic and primal conflicts; in this case, it’s at least obvious that a powerful man has been humbled as women have asserted their power. But the fairy tale of the film The Wizard of Oz is deeper than that and can’t quite be presented in a book or reproduced now, in the same way that a new Bugs Bunny cartoon can never fool you into thinking it’s a classic from the 1940s. The timing, gestures, and even breathing of the actors in The Wizard of Oz is ineffably bound to Hollywood in the 1930s. The Wizard of Oz, by the way, didn’t do badly in 1939, but its status as an American classic, by some measures the most-seen film of all time, only came after it began airing on television in the 1950s. For reasons I’ll address later, by the 50s even Disney films looked a lot shabbier than they did in the late 1930s. The Wizard of Oz caught lightning in a bottle partly because it never feels cheap in any sense, including emotionally. In some ways only comparable to King Kong, The Wizard of Oz comes to us as a singular fairy tale of Classical Hollywood itself; we imagine ourselves making and helping lifelong friends on repurposed MGM sets while singing original songs that instantly become classics.

One cannot overestimate the effect of songs, written by Edgar “Yip” Harburg and Harold Arlen, like “Ding Dong! The Witch is Dead,” “We’re Off to See the Wizard,” “If I Only Had a Brain,” and “Lions and Tigers and Bears, Oh My.” This music infuses the movie with unusual bonhomie, playfulness and whimsy. Recall that in the 1930s, no feature films were made only for children; they were instead made for everyone. The Wizard of Oz evinces an exquisite balance between the juvenile and the mature, probably best represented by Judy Garland’s exquisite performance of Dorothy, navigating a yellow brick road between innocence and gravitas. Rushdie writes, and he’s not wrong, that when Garland sings “Somewhere Over the Rainbow,” she gives the movie its soul. The song is perfect for a post-Code feminist: Dorothy achingly wants more, but ultimately seems happy with less. We remember Dorothy for her power partly because she is so respected; other than the wizard before we learn of his humbug, no one, not even the Wicked Witch, condescends to her in any way.

Influenced by: 1890s politics (in the original novel), Snow White (convinced MGM to spend $3m)

Influenced: for generations of kids, often the first “gateway drug” to great cinema

~

A17. Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (Capra, 1939) BO clip imdb LB RT trailer wiki

stream on amazon watch analysis by Koren read analysis by Nelson listen to my podcast

“You all think I’m licked. Well I’m not licked. And I’m gonna stay right here and fight for this lost cause. Even if this room gets filled with lies like these.”

The Mister Jefferson Smith of the title is from a conspicuously unnamed state out west, and the story is about sophisticates making fun of Smith’s bumpkin yokel naivete. In fact, Frank Capra had already made such a film in 1936, called Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, in which Gary Cooper plays a man who goes from a fictional small town to New York City where everyone takes advantage of him, including a woman played by Jean Arthur in her first lead role, but eventually the Arthur character sees his goodness and becomes a better person. Mr. Smith Goes to Washington came from an unpublished story loosely based on the real story of a new senator from Montana, but was written as a script to echo Mr. Deeds, and Capra prepared to make Mr. Deeds Goes to Washington until learning that Cooper would be unavailable. At that point, Cooper reteamed the young leads he had directed in 1938’s highest-grossing film, You Can’t Take It With You, which meant that for the second straight year Arthur’s name would appear first on a new poster ahead of the relatively unknown James Stewart.

One difference between those films and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington is that Joseph Breen at the Hays Office didn’t like the initial script, issuing a stern warning that its “unflattering portrayal” could be considered “a covert attack on the Democratic form of government.” Perhaps Breen would have preferred they change the film’s name to Jefferson Smith Goes to Washington and Quotes Lincoln? Granted, Breen wrote his apparently patriotic words in 1938, when MGM and Paramount were considering making the film; the official script was submitted with Frank Capra attached about a week after Capra won his third Best Director Oscar in five years – for You Can’t Take It With You, following Mr. Deeds Goes to Town and It Happened One Night – and at that point Breen utterly reversed course, writing that it “splendidly emphasized the rich and glorious heritage which is ours and which comes when you have a government ‘of the people, by the people, and for the people'”.[4]

Breen was at least partly reacting to Capra’s reputation for wholesome, homespun, populist entertainment, summarized by the emergent term Capracorn. Frank Capra also knew of the term, and now that he had succeeded at being the first non-actor to contractually require his name above his film’s title – as recounted in his autobiography, called “The Name Above the Title” – Capra turned his attention to complicating the Capracorn sobriquet. Mr. Smith Goes to Washington would celebrate the naïve innocent outsider, of course, but also pivot to a new realism, which some called bitterness, about the entrenched, cynical status quo.

Jimmy Stewart as Jefferson Smith exquisitely embodies this new approach to Capracorn, because he maintains all the folksiness and guile of Gary Cooper while also providing just a soup-sahn more fury and righteousness. In America today we discuss removal of any politician who has physically abused one person once; soon after Mr. Smith arrives in Washington, a montage shows him punching reporter after reporter. Smith’s frustration comes because he senses that after the death of his Senator, the political machine has chosen him, a leader of the Boy Rangers, as a stooge they can easily manipulate. Smith tries to pass a bill for a national Boy Rangers camp – the real Boy Scouts wouldn’t allow the use of their name – only to see the bill thwarted by corrupt Senators, including men he had believed in, who are using the site for kickbacks on a dam. In the film’s most famous scene, its denouement, Mr. Smith resists the corrupt Senators with his last recourse, a quixotic filibuster on the Senate floor, speechifying “you think I’m licked? well, I’m not licked” before finally collapsing. Perhaps every politician since 1939, and not a few other whistleblowers in other professions, have at some point seen themselves as Mr. Smith in this scene, the lone righteous American deploying his rights against a sclerotic establishment.

Influenced by: populism and little-guy-against-the-system narratives

Influenced: filibusters, whistleblowers, political movies, movie-like politics

~

A18. Gone with the Wind (Fleming, 1939) BO clip imdb LB RT trailer wiki

stream on amazon watch analysis by coldcrashpictures read analysis by Haskell listen to my podcast

“As God is my witness, I’ll never go hungry again.”

No other film can boast as famous a process, from the thousand-plus actresses who auditioned to play Scarlett O’Hara to the thousands of pounds of red clay shipped from Georgia to Los Angeles to the dozens of dormant sets burned to signify General Sherman’s razing of Atlanta to the four A-list directors who were hired by, fought bitterly with, and fired by, producer David O. Selznick. Victor Fleming is the film’s credited director, and some have written that when you add that to his director credit on The Wizard of Oz, Fleming’s one-year accomplishment rises above that of other directors with a two-masterpiece year like Francis Ford Coppola in 1974 and Steven Spielberg in 1993. Yet if Gone with the Wind has an author, it’s Selznick, who made all the final decisions on GWTW in his determination to disprove Irving Thalberg’s famous almost-last words to Louis B. Mayer to explain why MGM would be passing on adapting Mitchell’s 1936 hit novel, “no Civil War picture ever made a nickel.”

Today’s students tend to notice that America’s two most important pre-World War II blockbusters, The Birth of a Nation and Gone with the Wind, are not only big hit Civil War pictures but also promote Lost Cause mythology, whereby the racist, secessionist Southern rebels of the 1860s are reconfigured as just and heroic. (Even Jefferson Smith’s big speech pays homage to Lost Causes, and it’s not clear if he meant to include Confederates.)

Gone with the Wind is about Scarlett O’Hara, magnificently performed by Vivien Leigh, the headstrong daughter of a Georgia plantation owner played by Thomas Mitchell in an Irish brogue strong enough to reassure the audience that the O’Haras are not Old Money. Scarlett seems to wish they were, based on her wardrobe and her desire to wrest the blueblood patrician Ashley from her friend Melanie, but finds herself courted by the more industrious, more mercenary Rhett Butler, played wryly by Clark Gable, just as the Civil War breaks out. In some ways Rhett is this story’s smart outsider compared to the blinkered Southerners, but the film follows Scarlett as she travels from their plantation, called Tara, to help the wounded in Atlanta as the war turns calamitous for the South. Tara and Atlanta go, with the wind, from Southern elegance to scorched earth. Despite General Sherman burning a swath of Georgia to the ground, Tara’s black slaves remain dutifully loyal to the O’Haras, perhaps partly because some of them make terrible mistakes, as when Prissy, played by Butterfly McQueen, fails to deliver on her promises of midwifery. Malcolm X would later comment that McQueen’s shrill, vexatious performance set black people back twenty years.

As regressive as Gone with the Wind was, Selznick could have made it worse. Destitute from the war, Scarlett starts her own business, and in the novel, in Margaret Mitchell’s words, “The negroes insisted on being paid every day and they frequently got drunk on their wages and did not turn up for work the next morning.” Scarlett is furious. “And she would never fool with free triggers again,” only Mitchell wrote a word that rhymes with “triggers.” Around this point onscreen, Scarlett rides her buggy through a shanty-town, gets attacked, and is saved by her former slave Big Sam. After a vengeful posse breaks up the shanty, Rhett artfully lies to the Yankee authorities, but the movie is telling a bigger lie: in the book, our sympathetic posse is part of the Ku Klux Klan. The point is that Gone with the Wind could have been worse for black people, but it was awful enough, especially considering Scarlett O’Hara spent decades as something of a role model for white women. This is deeply problematic even when you attempt to factor out race: after Rhett and Scarlett marry, he commits marital rape, from which Scarlett wakes up the next day as though it was just what she needed all along.

All that very much said, some, like Thomas Cripps, have argued that the film somewhat normalized aspects of white-black allyship, leading to the non-production of scripts that were actually more racist. The film remains compulsively watchable, and it provided some permanent aspects of popular culture, as when Scarlett vows that she’ll do what she has to as long as “I’ll never be hungry again,” or when Scarlett asks what she will do if Rhett is really leaving her for good and he answers, “Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn.” (Strictly speaking, “damn” was forbidden by the Code, but apparently Breen gave less of a damn at the end of an almost-four-hour film.) Gone with the Wind was nominated for a then-record 12 Academy Awards and won 8, including the first Oscar won by an African-American, for Hattie McDaniel’s bravura performance as Mammy. The most significant legacy of Gone with the Wind’s sweeping set-pieces and melodramatic flourishes, at least in Hollywood, were that they served as the ur-model for the epic blockbuster in the 1950s, when Hollywood felt keen competition from television and responded by mounting many melodrama-driven spectacles.

Influenced by: updated Lost Cause mythology, Margaret Mitchell’s Atlanta upbringing (the novel), David O. Selznick’s ideas of the South (the film)

Influenced: ideas of the South; later stood as the ur-blockbuster to be aspired to

~

A19. The Grapes of Wrath (Ford, 1940) BO clip imdb LB RT trailer wiki

stream on amazon watch analysis by ReThink read analysis by Sobchack listen to my podcast

“Wherever there’s a fight, so hungry people can eat, I’ll be there. Wherever there’s a cop beatin’ up a guy, I’ll be there.”

John Steinbeck’s novel “The Grapes of Wrath” is about the Joad family watching their land, faith, and opportunities taken away from them amongst Dust Bowl conditions in Oklahoma. The Joads set off on Route 66 for the promised land of California, lose Grandpa and later Grandma along the way, and arrive to find conditions almost worse than they were in Oklahoma, the migrant farmer campgrounds policed like concentration camps. The Joads move from one camp to another, and when Tom Joad sees his friend killed, Tom accidentally kills a guard and becomes awakened to larger issues of social justice.

Director John Ford kept most, but not all, of this. While the novel ends with the downfall and likely breakup of the Joad family, Nunnally Johnson’s film adaptation ends more optimistically, with the family arrived in the cleanest and least authoritarian of three California camps, and Ma Joad saying that she “ain’t never gonna be scared no more.” Despite exploitation by the rich, Ma Joad says, “They can’t wipe us out, they can’t lick us. We’ll go on forever, Pa, cos we’re the people.” In the film, these platitudes are preceded by the more famous speech with which Steinbeck ends the novel, in which Tom proclaims his solidarity with the repressed, saying “Wherever there’s a cop beatin’ up a guy, I’ll be there. I’ll be in the way guys yell when they’re mad. I’ll be in the way kids laugh when they’re hungry and they know supper’s ready, and when the people are eatin’ the stuff they raise and livin’ in the houses they build, I’ll be there, too.”

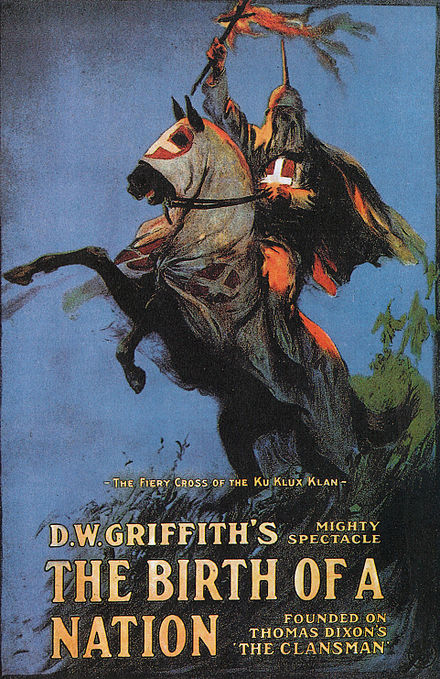

Although there are other great films that celebrate labor movements, like The Salt of the Earth and Norma Rae, The Grapes of Wrath is special partly because it was actually filmed during, and captures genuine pieces of, the Great Depression. Fox was probably over-worried about the timing: even in summer 1940, much of the country was still working its way through severe economic hardship that didn’t really end until the United States entered World War II. Of course, studios always reckoned with that tricky question of whether audiences wanted escapism, or preferred to see some kind of realistic “suffering.” For the record, The Grapes of Wrath did fine business amidst rapturous reviews. But the film’s legacy goes beyond business and reviews: it has become a lodestar of labor relations and partial inspiration for migrant workers of all races and creeds. Cesar Chavez’s famous speech “The Wrath of Grapes” doesn’t confront the 1940 film as much as continue Steinbeck and Ford’s story.