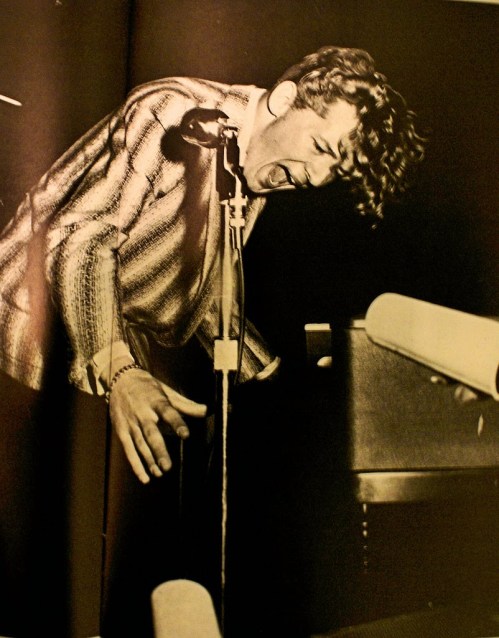

Against all conceivable odds, expectations, predictions, rumors, gossip and reason, Jerry Lee Lewis is 75 years old. He still sounds like he could hit the key of a piano with his pinky harder than most men could hit it with their right fist. His legacy—a smoldering trail of mayhem and musical masterpieces that stretches from here to Ferriday, Louisiana—was forged with the scorching barrelhouse piano and Pentecostal brimstone holler with which he has haunted and taunted country music and rock and roll for five decades. Slandered by scandal, hobbled by addiction, and fueled by a defiance that borders on vengeance, Jerry Lee has lived to stand his ground in the 21st century, playing the same music he has played since 1956, daring you to dismiss it.

“Mean Old Man,” Jerry Lee’s new album—which follows 2006’s hugely successful “Last Man Standing,” and utilizes the same formula of pairing Jerry Lee with conventionally recognized superstars for a set of covers—is no I told you so. It’s just Jerry Lee doing what Jerry Lee has always done. It is loose, spontaneous country, rock and gospel, delivered by one of the last living inventors of rock and roll on the instrument he taught himself as a poor boy growing up a thousand years ago in the pre-War south. That’s all. And if at times today’s stars seem like mosquitoes buzzing around the head of a lion (Kid Rock on “Rockin’ My Life Away”) or a little campy (Mick Jagger’s Broadway drawl on the Stones’ fake country classic “Dead Flowers”), they are to be forgiven—even admired for their willingness to get in there and do it.

There was a famous argument between Jerry Lee Lewis and Sam Phillips recorded at Sun Studios in 1957. Late one night, after a long session—the bottles had been opened and emptied—Phillips wanted the band to cut a song written by Jack Hammer and Otis Blackwell that he thought would be perfect for Jerry Lee. Jerry Lee refused. He heard evil in the lyrics; to sing them would be a sin. Just 22, he had been kicked out of Southwestern Bible College a few years earlier for playing boogie-woogie in chapel and had made his way to Phillips in Memphis under the absolutely outrageous but remarkably accurate assumption that anybody who could make a star out of Elvis Presley could make a star out of him too. By the time session engineer Jack Clement had the good temerity to hit record that night, Jerry Lee had begun to testify.

“H-E-L-L!” Jerry Lee spells, furious. “It says make merry with the joy of God. Only! But when it comes to worldly music, rock and roll, anything like that: You have done brought yourself into the world and you’re a sinner! And no sin shall enter there. No sin! It don’t say just a little bit. It says no sin shall enter there. Brother, not one little bit.”

The older Phillips tries to counter with a professorial differentiation between faith and extremism, arguing that you can play rock and roll and do good, help people—even save souls. Jerry Lee explodes.

“How can the Devil save souls?” he screams. “What are you talking about? Man I got the Devil in me! If I didn’t have, I’d be a Christian!”

The tape cuts off, but somehow, eventually, Jerry Lee relented and recorded the song. It was “Great Balls of Fire.”

The point being: The guest artists on “Mean Old Man” are singing duets with someone who believes his music has served the Devil—and has played it for 50 years anyway. Cut them some slack.

Still, the best moments on “Mean Old Man” come when nobody is trying to out-Jerry Lee Jerry Lee, including Jerry Lee himself. Everyone shines on the country numbers, which—like Lewis’ impeccable, chart-topping late-60s and early-70s renditions of classics like “Another Place, Another Time” and “What Made Milwaukee Famous”—teeter with weariness, regret and soul.

Jerry Lee’s cracking voice betrays the sadness and futility in “Middle Age Crazy” and Tim McGraw wisely lets the mournfulness hang in the air. “Swingin’ Doors,” his duet with Merle Haggard—two men that for public safety probably shouldn’t be allowed in the same city, much less the same room—is a lighthearted, Saturday night sigh of relief. And the unlikely pairing of Jerry Lee and Gillian Welch on the Eddie Miller country standard “Please Release Me” creates a rural church harmony that serves as one of the album’s true gems.

After a version of the Carter Family’s “Will the Circle Be Unbroken” that finds Jerry Lee trading verses and sharing choruses with soul powerhouse Mavis Staples, “Mean Old Man” ends with a solo performance of “Miss the Mississippi and You.”

It is a resonant ending. First, the Staples duet: country and gospel, black and white, blues and honky tonk, secular and spiritual, combining to pine for a better home in the sky; then, the man alone at the piano, singing softly into the darkness, like its his only comfort in the world.

–Ari Surdoval

I bought this CD a few weeks ago. I believe it is one of the best albums of music ever recorded. I was watching Jerry Lee’s first performance on national TV-the famous Steve Allen Show- and I have been amazed by him ever since.

Funny, I really agree the “stars” who perform with him on Mean Old Man-all except Mavis Staples-hardly register.

The last two cuts are worth the price of the whole thing.

I have been a playing musician since age 15…I feel very fortunate to have heard this music.

Mark