Unpacking Johnny Cash post-”Hurt” is a tricky concept. The prevailing narrative around Cash’s Rick Rubin-produced late-career records (recorded from 1993 to 2002) is that Rubin rescued him from a personal and professional nadir. This was precipitated by years of drug addiction (Cash had entered rehab most recently in 1992) and an ill-fated attempt at repeating the success of his “funny” songs like “A Boy Named Sue” and “One Piece at a Time” with one of his worst songs, “The Chicken in Black,” a song about Cash’s brain going into a chicken and Cash getting a bank robber’s brain.

So Rubin gets Cash to record a bunch of stripped-down songs, a lot of them covers by contemporary artists, and — along with the impeccable art direction of the American series packaging, which relied on Martyn Atkins’ stark photography — the resulting series of records restored Cash’s gravitas, cemented his status as elder statesman and ushered in a new template for the late-career renaissance of an aging icon. The highlight of the American series is, of course, Cash’s devastating take on the Nine Inch Nails heroin ballad “Hurt,” which has become the chief entry in the ever-popular listicle, “TK Cover Versions that Are Better Than the Original.” The eerie Mark Romanek video was many Millennials’ introduction to Cash, and NIN mastermind Trent Reznor went on to say that “Hurt” “wasn’t his anymore.”

Anyway, all of this is to say that to approach Cash from a post-”Hurt” vantage point critically is to cut through a swath of dense associations and narratives, all of which have this super-serious sepia tint to them that threatens to obscure one primary facet of Cash’s career, which is that he was a messy bitch who lived for drama.

I’m using obvious hyperbole here to prove a point, which is that, even before Cash was intoning shit like “God’s Gonna Cut You Down” and claiming that the dogs on the American Recordings album cover stood for “sin and redemption,” his career had a theatrical, melodramatic flair that could tip into the hokey. Of course, two things can be true at the same time, and in this instance, it can be true that Cash both loved a good story and was an authentic-ass Real American Man.

So: Mean As Hell. This album is actually a truncated version of Johnny Cash Sings the Ballads of the True West, a double LP released in 1965 that featured songs linked by Cash’s narration and their thematic focus on the American Old West. Mean As Hell was released as a single LP the following year and featured a trimmed-down tracklist that excised much of the narration.

We can probably safely infer that Cash was taking this shit extremely seriously, given the fact that in 1965 and ‘66, America was knee-deep in the British Invasion, Marty Robbins was six years past “El Paso,” and one of the biggest country records of the year was Chet Atkins Picks the Beatles. “Country Rock,” as exemplified by the Band, was at least two years out, A Fistful of Dollars was just about to break the spaghetti Western in America — the point I’m trying to get at here is that had Cash not been passionate about these songs and the mythological American West they occupy, they probably wouldn’t have made it to record, given their status as outliers in the prevailing music industry trends of the time.

Mean As Hell opens with “The Shifting Whispering Sands, Pt. 1,” which is a ridiculous song, as it turns out. The song was written in 1950 as a poem and by the time Cash got to it in 1965, had already been recorded by Billy Vaughn (with narration by Beat icon Ken Nordine) and Rusty Draper. Cash’s version hews pretty closely to Vaughn’s version.

Here’s the thing, though: I have no goddamn idea what this song is supposed to be about. Ostensibly, it’s narrated by a gold prospector who wanders in a dry valley, surrounded by death and the titular sands. But there’s a degree of narrative ambiguity to the song; the lyrics freely admit that the prospector has no idea how he escaped the valley, only that “to pay my final debt for being spared / I must tell you what I learned out there on the desert.”

There’s a Stephen King short story called “Beachworld” that’s about a group of astronauts who crash-land onto a sandy planet and gradually realize the sand is not as it seems. I would dearly like to believe that King was inspired to write “Beachworld” by the vaguely sinister implication of “The Shifting, Whispering Sands” that the sand in this valley is somehow alive and hungry for human flesh, and that the narrator has been spared from a grisly fate out in the desert by the sand and returned to civilization to lure others to a similar doom. Anyway, I’ve tweeted at him about it. Thank you for coming to my TEDTalk.

Despite my love for Cormac McCarthy, I’ve never gotten with horses. Horseback riding, in central Pennsylvania at least, was an upper-middle-class affectation that made zero sense to me, and my scorn for it was abetted by the fact that horses freak me out, what with their horrifying screams, big weird faces and teeth and also this nightmarish drawing of a horse wearing one high-heel that Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark embedded in my subconscious when I was 5.

Anyway, “I Ride an Old Paint” does nothing to abet the vaguely sinister air established by the possibly sentient sands of the first track. There’s a definite trope in post-millennium horror films of using overly-syrupy songs from the ‘50s and ‘60s incongruously next to shocking or graphic imagery. But it’s a real chicken-or-the-egg question: Is there something subconsciously sinister in the cloying string arrangement juxtaposed with Cash’s echo-laden baritone, or is just the fact that the song is literally about a man requesting that his bones be tied to his horse’s saddle after his death so they can continue to ride together?

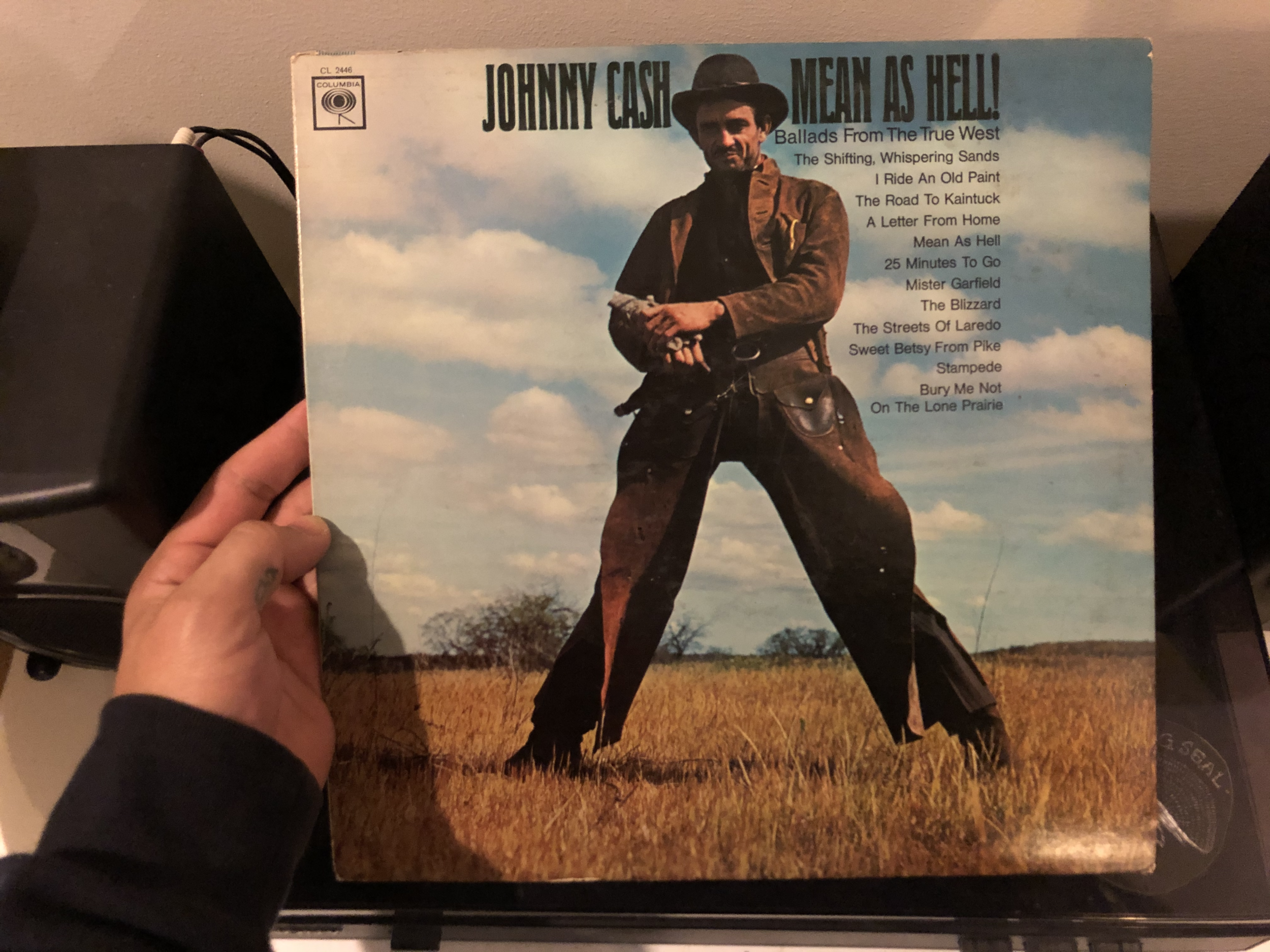

If Cash’s greasepaint facial hair on the album cover didn’t convince you of his theatrical bent, perhaps “The Road to Kaintuck” will. Relying on the thorny concept of Kentucky as “the dark and bloody ground,” this is one of the Cash originals on the record, chalked up as a co-write between he and wife June Carter. It’s actually one of my least favorite songs on the record, despite the presence of reliable Cash foils The Statler Brothers on backing vocals, partially because it relies on what I like to call the Robbie Robertson School of Anachronistic Songwriting, in which a series of old-timey namedrops and references — in this case, Daniel Boone, Michael Stoner and Moccasin Gap — takes the place of any coherent characterization or narrative.

“I asked Mother Maybelle Carter one night to write me a Western song for this album,” Cash writes on the Mean As Hell sleeve. “The next morning she gave me this. Since the Bible on the plains was as uncommon as a letter from home, many cowboys called it that.”

Far be it from me to call Cash a liar, but I can’t find anything to back this up. The anecdote is, however, illustrative of the hilarious tenor of the writing on the Mean As Hell sleeve, which includes Cash’s claims that he prepared for this record by “[sleeping] under mesquite bushes and in gullies … [sitting] for hours beneath a manzanita bush in an ancient Indian burial ground and [breathing] the west wind and [hearing] the tales it tells only to those who listen.” He adds that he “ate mesquite beans and squeezed the water from a barrel cactus,” “learned to throw a bowie knife and kill a jack rabbit at 40 yards” and “was saved once by a forest ranger, lying flat on my face, starving.”

Anyway, that’s obviously all bullshit. Cash recorded or released seven albums between 1964 and 1966. While the notorious California wildfire incident occurred in 1965 and at least one article does mention that he liked to take off into the wilderness near Maricopa, CA for fishing trips/drinking binges, I can’t find anything to support the notion that he took months during this hectic schedule — which presumably also included live performances, TV appearances and arrests — to nearly die in the Western scrublands while learning how to kill a rabbit with a knife from 40 yards out. Myth-making in action!

“Mean as Hell” is, um … bad? It’s sort of a halfway point between the rest of the record’s actual songs and the spoken-word stuff that’s included on the True West double album. But there’s no melody to this song, with basically just Cash’s guitar as backing, and it doesn’t even succeed as prose. Opening with the fairly promising conceit that basically posits God and the Devil made a bargain to establish a new Hell around the Rio Grande, it devolves into poop jokes about Mexican cuisine and manages to fit both the death of a horse and a calf into the last 30 seconds. It’s hard to fuck up a song that takes “Texas blows” as its main premise, but hey, kids, drugs are bad.

“25 Minutes to Go,” by contrast, is everything that’s great about vintage Cash in a tight three minutes. It’s also written by beloved children’s author Shel Silverstein, who would also provide Cash with a hit in the much more popular “A Boy Named Sue.” Cash wasn’t the first artist to cover “25 Minutes” on record; that honor belongs to the Brothers Four, who released a version in 1962. (Silverstein put out his own version on his Inside Folk Songs, which also came out in ‘62.) Unfortunately for this record, Cash’s wildcat version on Live at Folsom Prison is the definitive one; his delivery is more unhinged, and the crowd is feeling it. The perversity of a guy who’d never been to prison singing a song about an imminent hanging written by a guy who’d never even been arrested to a crowd of prisoners… that’s just *chef’s kiss.*

Cash says he got this song from Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, which I love, because it’s one entirely self-invented cowboy sharing songs with another. It’s got an agreeable sort of amble as it proceeds, and the big refrains have both the Carter Family and the Statler Brothers joining Cash, an approach that reminds me of nothing so much as a lo-fi version of the stomp-clap “HEY”-folk microgenre practiced by the Lumineers and their ilk. (I mean that as a compliment.)

Cash also really bites into his dialogue here, most of which he wrote himself — his asides about the President and First Lady’s nicknames for each other always make me chuckle. Ol’ JR could always put a lackluster arrangement over by the sheer force of his charm, and this song is a great example of that.

Just a perfect, depressing little Old West tale. These tight, economical song-stories from this era of country music should be taught as literature. The way the chorus changes as the story progresses and of course the gut-punch closing verse … it’s like Charles Portis. Truly an underrated Cash deep cut in my opinion. (The overly-bright tack piano, though, is the one element of the song I take issue with, though I suppose it does leaven the crying-in-your-beer overall mood .)

This song is a great case study. Sad-cowboy warhorse “The Streets of Laredo” is an old song. I mentioned earlier how you can use Marty Robbins’ Gunfighter Ballads and Trail Songs to contextualize Mean as Hell/True West, because the Robbins record, which came out in 1959 — a year after Cash had his first big post-Sun Records hit with “Don’t Take Your Guns to Town” on Columbia — was a huge hit. It was certified gold in 1965, the same year Cash recorded this record. And Robbins’ follow-up, More Gunfighter Ballads and Trail Songs, which came out in 1960, had a version of “Streets of Laredo.”

Cash and Robbins were linked by more than just genre and label (here they are duetting on this very song in 1969). Cash writes on the Mean as Hell sleeve that the idea of an album of Western songs was pitched to him by Columbia producer Don Law in 1961-2. And guess who produced both Gunfighter Ballads albums for Robbins? Don Law, baby! If the music industry knows one thing, it’s how to milk a concept.

As I mentioned before, Cash covered “Streets of Laredo” on American IV (the one with “Hurt”) and it’s instructive to listen to the two versions back-to-back.

This is one of the troubles of dealing with late-period Cash: The narrative surrounding these albums, and particularly IV, the last one released during his lifetime, is impossible to separate from the actual sound. Do I like the sparser instrumentation of the American version of this song, even though Cash’s voice (hitting some truly impressive low notes) is unquestionably in better shape on the 1965 version? Or am I just so conditioned to equate the latter version with unimpeachable authenticity and fraught, end-of-life emotional heft? Hard to say.

I don’t like this song, so I’m going to talk about the idea of the Old “Wild” West and Frontier America that Cash is mining on this record.

British historian David Hamilton Murdoch’s The American West: The Invention Of A Myth posits that “The Wild West” as a pop culture construct dates back to the turn of the century, when America, with the frontier closed and settled, was still trying to figure out what it meant to be an American. Aided by mass media (newspapers, dime novels, touring shows, movies, even paintings and illustrations), the American Frontier/West became “The Wild West,” and the stories that cropped up about it passed from fact into idealized myths that quickly became foundational to the national character.

For Cash, who was born in 1932, his window out of rural Arkansas as a boy was the radio, and there were a large number of narrative radio Westerns he could have been hearing at that time. Then, Cash went into the Air Force in 1950, at which point Hollywood was moving into the Golden Age of its Western-dominated era, with foundational genre classics like Broken Arrow (1950), High Noon (1952), Shane (1953), Wichita (1955), The Searchers (1956), and Rio Bravo (1959), all films Cash could have seen at one point, either while serving, or after he settled in Memphis. And he was a touring musician by the time television like Gunsmoke, The Rifleman, Rawhide and Bonanza were going strong in the late ‘50s, which means he probably saw a good bit of Western TV in hotel rooms.

Cash was born too late to experience anything of the actual Old West; his entire concept of it came from a concerted, decades-long, cross-medium mutation of history into drama and drama into myth. With this record, Cash steps into the lineage of people like John Ford and every nameless dimestore novel scribe who wrote breathlessly about Wyatt Earp. And if there was anyone prepared to be fully, “authentically” immersed in an exaggerated myth, it was Johnny Cash.

I’m sorry, I can’t take this shit seriously. It’s where the schtick curdles the most for me, and it’s definitely not helped by the guys who are doing the “stampede!” backing vocals, who are either wasted or purposefully fucking up the whole thing. I can’t listen to them all trip over each other to yell “Stampede!” with all the vigor of men who have been at this shit for eight hours and just want to go home without laughing. Good Western Death™ in there, though; I give it an A-.

So, another one Cash revisited for the American series — this time, on the first record. It’s not really a fair comparison, though, as the version on this record is much more of an actual Song, whereas the American version is a long, mostly-spoken version that incorporates the entirety of Badger Clark’s famous “A Cowboy’s Prayer” as an introduction. Clark was an interesting figure: He was South Dakota’s first poet laureate and lived alone for years in a cabin with no electricity, running water, or telephone, on land that is now a state park. In other words, he was the real deal in a way that Cash was not. Cash would have presumably been aware of the poem after a life lived in country music; even Sarah Palin has name-checked it.

But it’s fitting that we close the record here, with these two versions. Older, wiser, Cash omitted most of the original song’s sad-bastard lyrics in favor of a hopeful poem about finding beauty in the natural world. (And again, this is a man who burned down several hundred acres of California forest the year True West was recorded.)

I thank You, Lord, that I am placed so well / That You have made my freedom so complete

That I’m no slave of whistle, clock or bell / Nor weak-eyed prisoner of wall and street

Cash sounds genuinely humbled, genuinely grateful as he’s intoning those words. After spending this long meditating on the invented Johnny Cash and the invented American West, it’s truly wonderful to hear him at his most sincere, reciting a piece of poetry that came from the real place he’d spent so much time working in a fictionalized shadow of.

I know that others find You in the light / That’s sifted down through tinted window panes

And yet I seem to feel You near tonight / In this dim, quiet starlight on the plains

I love hearing this line about the divinity of nature from him. The two versions of this song are odd siblings: One appeared the same year Cash, high on fame and pills, literally destroyed a swath of the natural world; the other arrived near the end of his life, when he was newly sober, humbled. In this instance, Cash the myth, Cash the man and the invented Old West he spent so long mining for stories and songs finally fall into alignment.